Saul Steinberg was the most cosmopolitan of cosmopolites. He was a victim of religious persecution who appears never to have practiced any religion. He fled European fascism, he was an Italian manqué, and he lived the quintessential American immigrant success story; he was poor and he was rich and in both cases he scrambled constantly for dough, he was a devoted son who detested his mother, he supported an enormous extended family; he was as self-centered as a toddler, he was learned and elegant, an uncompromising professional and a goofy, gentle joker. He was celebrated and loved and he was depressed and solipsistic, as bleak in outlook as the Russian novelists he admired all his life; he was an incorrigible, indefatigable philanderer whose marriage to his brilliant, long-suffering, exasperated wife lasted fifty-five years, until his death in 1999.

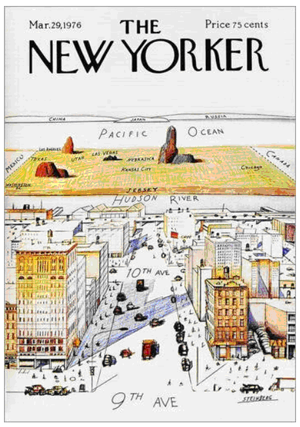

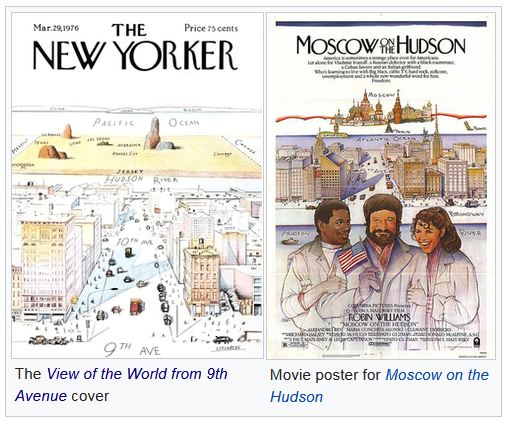

And he became insanely famous for producing a drawing that he himself, by the end, couldn’t stand—an Iconic Image if there ever was one—a meme, before there were memes—“his bane,” according to his great friend Ian Frazier. You’ve seen it a million times. It’s called “View of the World from 9th Avenue,” and it was the cover of the New Yorker on March 29, 1976, and I’m betting you don’t know what it means. I didn’t either, until a few days ago.

I was looking into this drawing because it had dawned on me recently that I’d never quite understood the joke. Was it “Oh New Yorkers! they think they’re the center of the world!”?? Or was it, “Well, it’s funny that they think that but also they are, right? ha-ha!” I saw in it a poking fun at the paradox, the small-mindedness of “cosmopolitanism.” Maybe, the artist’s little joke against himself.

Was I ever wrong! Not one person whom I’ve asked about this drawing understood what Steinberg meant by it, even though the answer is written plain as day in the weird and excellent 2012 biography by Deirdre Bair—and still more clearly in the image itself, once you know how to look. It turns out the answer matters, too; it matters a lot.

Steinberg was born in 1914 and grew up in what he himself considered the middle of nowhere, a town called Râmnicu Sărat in Romania. He was the great hope of a working-class family, a gifted boy whose education and talents, it was hoped, would bring prosperity to them all; in the event, they really did.

But anti-semitism was rising fast all through Europe. Steinberg described his childhood and adolescence to his college friend Aldo Buzzi as “a little like being a black in the state of Mississippi,” in the memoir Reflections and Shadows. “I had no rights, and went to high school wearing a name plate with a number, like an automobile.”

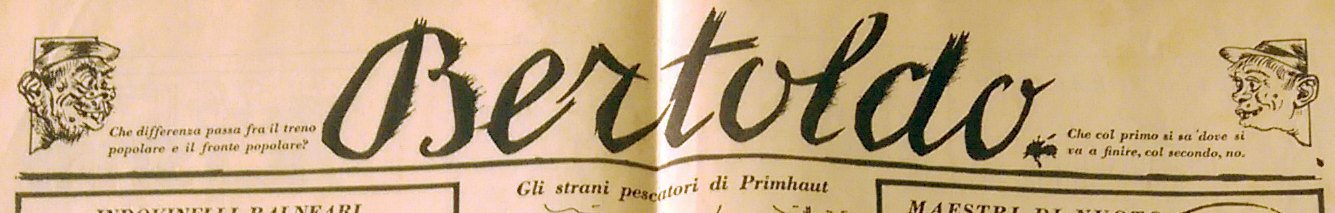

Steinberg was saved, like many an unhappy adolescent, by books, acquiring a taste for Dostoevsky, Chekhov and Gorky, and becoming “anaesthetized,” he said, by Jules Verne. In 1933 he went to Milan to study architecture—a respectable profession, of which his ambitious parents would approve. But soon after he arrived in Italy he rocketed into his métier, and began cartooning at a satirical paper called Bertoldo. Immediately he commenced to live like the artist, dandy and bon vivant he was born to be. His best girl, Ada Ongari, was evidently a smuggler on the black market. (There were a lot of other girls too, but he stayed close with Ada for the next six-plus decades. He left her a lifetime annuity of $12,000 in his will.)

Bertoldo was surpassingly meek on the “satirical” side, given to incomprehensibly elliptical political fables, sexist jokes and mild surrealist fancies rather than anything resembling confrontation; this was necessary in order to get things past the increasingly aggressive Fascist censors.

I have a copy from July of 1937, summer themed. Only a few weeks before, Picasso had completed his painting, Guernica, in response to the world-shocking bombing of the Basque town of that name by the Luftwaffe and Italian Fascist forces at the request of Franco’s Nationalist government on April 26th. More than a thousand people died, in one of the first bombings of civilians leading up to the second war.

The only reference to Spain I can make out in this issue of Bertoldo is a joke at the top of one page, a play on words between “tourist train” (treno popolare) and “Popular Front” (fronte popolare):

Che differenza passa fra il treno popolare e il fronte popolare?

Che col primo si sa’ dove si va a finire, col secondo, no

What is the difference between the tourist train and the Popular Front?

With the first one you know the destination, with the second, no.

Doubtless a lot of these jokes and stories are going clean over my head, but the general vibe of Bertoldo is resolutely trivial. It’s got a lot of cartoons like this one:

[Beach Riddles]

“What do you call that animal that pinches you so hard under the water?”

“Gaston.”

There’s a little column called I bet you a thousand lire! (about $715 in today’s dollars):

I bet you a thousand lire that there is no woman, young or old, however hideous, who, upon showing her pass on the tram, won’t lower her gaze all bashful and say: “Please don’t look at the photo: it is not a good one!” completely deluded—the hag!—that in real life she is a hundred times lovelier than her picture.

I bet you a thousand lire that even though there are many honest men around, you will never find somebody who, upon knowing that the authorities are looking for him, won’t feel distressed and uneasy and won’t then act like a chicken.

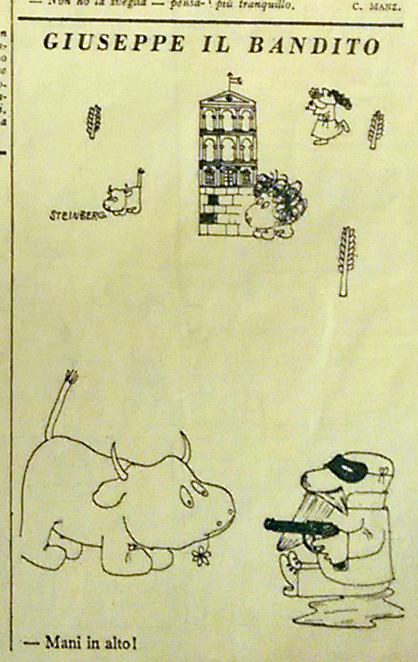

In the midst of all this there is one signed Steinberg cartoon. He was all of 23 when it was published, but his vision is complete and distinct, consistent with what will come: the bewilderment of innocence confronted with thuggery, the sheer ludicrousness of it, the total inability of a bull (a bull?) to stick ‘em up (Mani in alto!). The confounded distress of being quite unable—however willing a little bull might be!—to comply with the demands of power.

(Okay… maybe this is a little crazy, an aside, but do this bull and the figures above him refer to Guernica? Like I was saying, the painting had only just been completed in time for the Paris Exhibition two weeks before this edition of Bertoldo came out: it was the commission of the Spanish government, specifically meant to draw international attention to the war, and there was a lot of press about it. There’s also a small echo of Guernica in the figure coming round the edge of Steinberg’s building. He could never have referenced Picasso directly, but was this a way of nodding to big news in the art world in a manner that might sneak round the censors?)

wikimedia commons

wikimedia commonsHe always avoided talking about this time in his life, but it can’t have been easy for him, no matter how many girlfriends and awesome threads he had.

Anyhow. It was only a matter of months before Steinberg was forbidden to sign his own published drawings, because in 1938 the Mussolini government made it illegal for Jews to work in most of the professions. Soon the Italian government started rounding up Hungarian and Romanian Jews as “undesirables.” Steinberg was detained briefly in an internment camp while he and everyone he knew labored frantically to get him out of Italy.

In general, Italians weren’t crazy about the anti-semitic laws, and many of them protected their friends as best they could but even so, things got hotter and hotter for the Italian Jews, nearly one-fifth of whom died in the war. Steinberg barely managed to get out of Italy in one piece in 1941, with permission to travel to the States obtained via a lot of pulling of strings in New York and Washington. By now his drawings were welcome everywhere, including at The New Yorker, where he would go on to publish nearly 90 covers and many hundreds of drawings.

He wasn’t quite thirty years old and he was a walking mass of paradoxes already. Successful, a wanted man, an exile, stateless, alone, with friends and loving relatives all over the world making sure he’d be okay; exquisitely cultivated, talented, headed for great things, in the middle of a war.

The minute he found a stable home in New York, his work prospered and his fame swelled. He made paintings, drawings, murals, advertisements and greeting cards, he wrote books, he made more and more money. Business was always good for him, it seems.

But it was not possible for even Deirdre Bair to fully catalogue the many and convoluted psychodramas of Saul Steinberg’s personal life in a 732-page biography, so I won’t attempt even a thumbnail sketch here. Suffice it to say that his romantic history makes Don Draper’s look pretty low-T and the Steinberg family was like something out of a telenovela, and all of this took its toll over the years. So by the time 1976 rolled around, he was in kind of a dark place. His much-loved sister Lica had died a few months before, of complications from surgery; at her graveside he wept for the first time since he was a boy in Romania, a half century before. His girlfriend, Sigrid, was very ill with depression. New York was at a low ebb, too, with rising poverty, unemployment and gas prices. A massive bomb had gone off at La Guardia. And Steinberg had started out well acquainted with the darkness, as we know.

When “View of the World from 9th Avenue” became the most-copied, most-admired and most ubiquitous New Yorker cover in the magazine’s history, Steinberg got really mad about the many shabby parodies and copies of it he saw all over. He finally got fed up and sued Columbia Pictures over their version, created to promote the film Moscow on the Hudson [Steinberg v. Columbia Pictures Industries, 663 F. Supp. 706 (S.D.N.Y. 1987)]. It took four years and a lot of grief, but he won. Columbia paid him nearly a quarter million dollars, that is, about half a million in today’s money.

I mention this because in his opinion, Judge Louis L. Stanton gave his view of the meaning of the image as follows: “The parts of the poster beyond New York are minimalized, to symbolize a New Yorker’s myopic view of the centrality of his city to the world.”

At the time I read this, I hadn’t yet read Bair. I was just asking everyone I met, you know that cover? The answer was always yes. “I saw it yesterday at the dentist’s office.” “My best friend’s parents have it in their family room.” “So many people had it up in their dorms. People from New York.” Okay, but why? What have people been thinking they were saying for the last forty-three years, putting this thing up on the wall?

So I thought I’d ask David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, what he thought about it, and the next thing I knew, there he was on the phone. (The following is lightly edited for clarity.)

DR: You’re doing a riff on the Steinberg cover?

MB: Well… you know I looked at it the other day, it is so familiar but suddenly I realized that I’ve never quite understood the joke. He himself was such a civilized guy, right? So cultivated, so elegant… and so I’ve never known where he landed, exactly, on that continuum between censure and praise, that the image suggests.

Oh, I think he was making fun of his adopted home city. This was a guy… born in like in an obscure part of Romania, as I remember the story… is lucky to survive all the obvious horrors of the 20th century. He winds up here, and you know…

[drifts off for a moment]

I knew him a little bit, I was really lucky.

Wow!

Yeah no, it was very cool, and I’ll tell you a hilarious story that is completely irrelevant.

He loved aspects of America so much that he like went crazy about it—for example, baseball. He would sit in front of the television watching a baseball game, and was fascinated by—to him it was just kind of a weird, artistic pursuit… you know, these people standing around on the grass waiting around for the ball to come their way, and the geometry of it—this distinctly American thing, in his mind—

The theater of it—

—and he would sit in a lawn chair, in his living room, in a baseball uniform!

So… Saul, I think he was making—you know, it’s not the most obscure joke in the world! The involutedness of New Yorkers!

Yeah! But is it a good thing, or a bad—is it a funny, like—

That’s just the thing… I mean, New Yorkers, if they don’t watch it? They live on an island! Or, a collection of them, or little bits of—jutting pieces of land, and that’s what that joke is all about, and I think it’s kind of relevant today too, pal!

[laughs thoughtfully]

New Yorkers… and I think he’s probably particularly making fun of New Yorker readers, circa nineteen seventy-whatever-it-was…

He was obsessed with maps… there were a whole bunch of them. Some of them were obvious, more like gags, and some of them, kind of existential jokes about words and maps.

Here’s the thing, I wanted to know what you thought about it, because you’re the quintessential New Yorker to me.

I’m the quintessential New Yorker, in that I was born somewhere else.

Right?

I mean, I wasn’t born in Brazil, but I was born across the river…

[…]

Saul was a hyper, hypersophisticated, self-aware guy. I think he must have known six or seven languages really well, too.

This relates to what I was going to ask you, though.

Gahead.

Cosmopolitanism. Which… I grew up desiring that desperately—six languages, that was what I wanted, I went to Paris, hung around at the cafe and smoked Gauloises, I mean… I embraced that European concept of sophistication that was very, hmm, codified, by people like Steinberg, and still is in some ways attractive to me. But I think that that world has changed completely.

Why is that?

That idealization, or internalization of what we considered European values, that came to us in the form of like I don’t know, Truffaut movies or something, Sartre, everything we read… I just don’t think things are like that anymore.

If you don’t mind, I would push back on the point; I mean look… it depends who you are. You talk about Americans, I mean—which ones? There are 330 million of us, and some people for sure are incredibly insular, and maybe more so than they were, but look at the… I just got back from the bookstore, and I was looking and seeing what was selling, and what was pop—it is so obvious that the biggest change in American fiction—in addition to many, many more women being present on the table, and selling, and the fact that most fiction sales are to women—is the immigrant novel. I mean just the immense range of immigrations from all over into the English-speaking world of the United States and Britain, and South Asia and all parts of Africa.

That’s exactly the point I’m making! That the world is actually the world, now, so much more than it was in Steinberg’s day.

I see… I see. Well, that may be so. That may be so.

Look, the first thing I wanted to do, from my little wormhole of a town, was to get out, and that meant, you know, playing guitar in the Metro in Paris, I lived in Moscow for years… nothing was more important to me. But you’re right, I don’t know that that’s anywhere near universal.

What you thought you wanted, then, when you wanted to get out of the wormhole—how defined was that, and did you achieve it? And if you were setting out from there now, would it be a different goal?

Well… I had the adolescent dream of escaping boredom. There are much more important reasons that people get out into the world. You know, escaping from unfreedom, or oppressions of all kinds. I was just a kid trying to bust out of Springsteenian New Jersey into something more… interesting, and that I was only hearing on the radio or reading in the magazines that were enticing at that time, and I got lucky, you know. In the sweepstakes of where you get lucky in life, and where you’re unlucky, I’ve had plenty of the latter, like any human being, in serious ways. But the lucky thing was to somehow manage, whether through the choice of some editor, or the ability to buy a People Express ticket at the right time, to see a good deal of the world when I was really young.

So this is obviously lovely, and sympathetic, and you get the feeling that when David Remnick looks out over the Hudson he sees all kinds of things, and I think that is what people want from this image: A reminder of all that really is out there. This is the upside of cosmopolitanism, of feeling at home with the world. Also, The New Yorker was kind of built to color in and to widen that view. People feel the way they feel about the drawing because of the way they feel about the magazine, and that’s part of why it’s so paradoxical, and so confusing.

But here’s what the drawing really means. Let’s start with Bair.

After the magazine’s legendary reader, “the little old lady in Dubuque,” enjoyed her moment of condescension with the cover [a moment of knowing condescension, that is, over provincial New Yorkers], she and the rest of Steinberg’s viewers wanted to know why none of his typical landmarks were included to identify the grandeur for which the city is famous. He had a ready answer: this was a drawing of how “the crummy people”—that is, the working classes—see the world that lies beyond their immediate neighborhood. He never intended to make people feel superior or even comfortable when they looked at this drawing, for his thoughts about America, particularly New York and its environs, had darkened considerably during the past decade.

There’s more to it than that, but this view really shocks you (or rather, me) into an entirely new consciousness of the drawing. It’s quite true, there is not one single symbol of New York’s wealth, glamor or power in this image. One supplies the idea of New York oneself.

The people in it—did you ever even notice that there are people in it? There are, there are a lot of people in it!—they are without character or expression, drawn in like ants. They’re not in a place of beauty or fascination—they’re not inhabiting the New York, in short, of The New Yorker—though they are literally inhabiting The New Yorker.

For many, perhaps, the glamor comes from the top few inches of the cover, the familiar name and font, printed over a drawing of what might have been intended to mean… just in part, at least… something like urban despair.

One so easily forgets how dark the 1970s were. The Son of Sam was coming to “the vengeful and paranoid America that let McCarthy ride and killed the Rosenbergs,” in Robert Hughes’s memorable phrase. The encroaching fears that beset the middle-aged artist, too, the pathetic “is that all there is”? feeling. That’s just the sort of thing I think Steinberg might have found, in the way of a Russian novel, both funny and sad.

Speaking of Hughes, he wrote one of his glorious capsule biographies (in Time) about Steinberg, calling “View of the World from 9th Avenue” “a classic commentary on the provincialism of great cities.” That is so, but now I think it is something more like, the provincialism is completely involuntary, a part of the malaise of the 20th century which, with understanding, we might yet transcend.

It’s a commentary on the way people trap themselves in big cities and won’t, or can’t, look up, or out over the water.

Steinberg was an intellectual artist, but not an esoteric one. People would compare him to Paul Klee and he didn’t really care for it; he once tried to explain the superficial similarity this way: “Klee and myself are both children who never stopped drawing.”

This speaks to a certain comfort with not knowing, with not needing authority. It’s a rare artist, a rare person who can let that need go. “Dubito ergo sum,” Steinberg once wrote; a joke, sure, but the funny part of it is that doubt might in fact be a better indicator of reality than any other.

Klee once said, “A line is a dot that went for a walk”—a fun paraphrase of Euclid. But Steinberg went him one better: “A line is a thought that went for a walk.” He didn’t like explaining his work to people; he just invited them on the walk.

“The sort of people who need explanation,” he said, “deserve a mystery.”