I suppose I first became an insomniac in high school. Caught between obsessive studying for exams which kept me up until 2 AM every day and a burgeoning terror of death from reading too much French existentialism in my free time, my body became permanently adapted to not sleeping for more than four to six hours at a time.

They say sleep is the cousin of death, after all. What terrified me about sleep was the sense of oblivion and non-existence—and the knowledge that I might fall asleep and never wake up again. So I’ve always had difficulty emptying my head of thoughts in order to fall asleep.

After twisting my knee in a bizarre New Year’s accident trying to prevent a drunk friend from jumping out of a moving car, I have been stuck mostly at home for the last month. Originally I planned, for the first time in maybe a decade, to stay in, rest, and sleep.

No such luck, despite the fact I’ve continually tried to force myself to sleep in order to recover faster. I guess I’ll have to resign myself to a permanent sense of tiredness for the rest of my days.

Perhaps it was the fact that I was trying to force myself to sleep that prevented me from sleeping.

People sometimes tell me that they’d never know how little I sleep if I didn’t tell them. Know this, friends! If you ever have a meeting with me before noon, there’s a strong chance that I just haven’t slept, and just decided to power through without sleeping—and while I’m having a conversation with you, all these distracting thoughts are running through my head, refusing to merge into a single, coherent voice.

I take full advantage of my life as a freelancer to keep strange hours, sometimes sleeping from 6 AM to 10 AM or 8 AM to 12 PM or 10 AM to 2 PM. I try to get up before sunset. I become neurotic if I see only night, but my schedule usually means I see both the sunrise and sunset each day.

Insomnia is undeniably useful for productivity. Unless I’ve checked off everything on that day’s agenda, I can’t relax. And living in Taipei, a highly nocturnal city, helps too. In my opinion, whatever they say about New York, Taipei is the real city that never sleeps.

So how do I keep awake?

Obviously, first and foremost there’s coffee. For me, that’s usually convenience store coffee; usually from 7/11 or FamilyMart, the two convenience stores within five minutes’ walk from my apartment. Starbucks in Taiwan is operated by the Uni-President Enterprise Corporation, which also owns and operates 7/11 here, so it has long been rumored that 7/11 uses the same beans as Starbucks. But 7/11 is much cheaper, with a large Americano coming out to 45 NT ($1.50). 7/11 coffee isn’t all that bad. FamilyMart coffee doesn’t taste as good as 7/11 coffee, but it’s a change of pace.

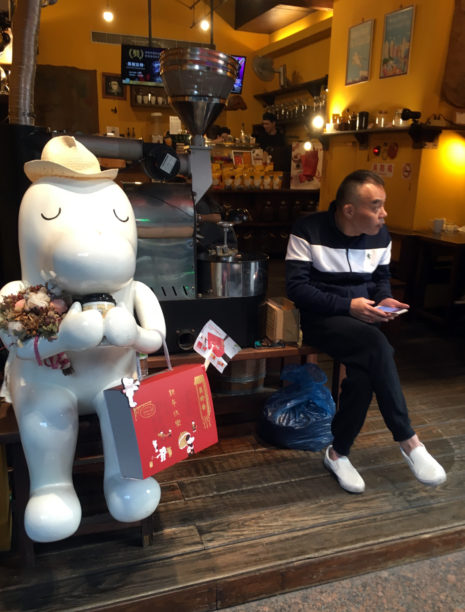

Man sitting in a Cama Coffee next to its mascot, a statue of which is featured in every store

Or if I’m feeling up to it, I might walk to a Cama Cafe or Louisa Cafe, both better-quality coffee chains. Despite having drunk tens of thousands of cups of coffee in my lifetime, I can’t say I understand coffee in the slightest (or alcohol, for that matter)—I just drink it. So I basically have no idea what “better quality” means, except that the coffee tastes better, and stronger. 60 NT ($2.00) will get me a large coffee at Louisa that probably contains more liquid than my bladder can hold, so I usually go for that.

No matter what season it is, even in the winter, I drink iced coffee. You can drink iced coffee right away, for immediate gratification, while with hot coffee you have to wait for it to cool down. I tend not to have the patience to wait. And if it is the winter, the coldness of the coffee just makes me more awake.

Since I have an addictive personality, I realized early on that if I took the path of using energy drinks I’d become dependent on them, so I just try to keep to coffee. I rely on energy drinks as a last resort for crisis periods in which I have no choice but to stay awake for over 24 hours in order to do reporting. The last two times I had energy drinks was in 2016, during the historic China Airlines strike, and in 2015, during the weeklong occupation of the Ministry of Education by high school students. Or sometimes, if I’m working at night, I might get a drink to give me another burst of energy—usually a can of Taiwan Beer, or sometimes, if I’m feeling adventurous, a small 59 NT bottle of kaoliang.

I also try to take small meals so as to avoid getting tired, or gaining too much weight. And I try to stick to spicy food, since the spiciness will wake me up. I’m not actually sure if it’s a Hakka thing or an Indonesian thing or just a family eccentricity, since my father’s family is Chinese-Indonesian of Hakka origin, but I’ve also taken to adding chili sauce to my rice or noodles the way many members of my dad’s family habitually do. My preferred convenience-store choices are microwaveable mapo tofu over rice—which, to be honest, is pretty bland compared to the real deal—and extra spicy instant beef noodles.

7/11 microwaveable mapo dofu packaging

While many of us are familiar with the wonders of Shin Ramyun, a Korean brand of spicy instant noodle found across the world (at least, the parts I’ve been in), Taiwanese instant noodles seem to have advanced the art of the instant noodle beyond what many of us are familiar with. Because some brands contain meat products, they aren’t easily exportable, and are thus scarcely seen outside of Taiwan. The inventor of instant noodles as we know them today, Momofuku Ando, was a Taiwanese man primarily remembered as Japanese, because he was born during Taiwan’s Japanese colonial period and spent most of his adult life in Japan.

Super spicy instant noodle packaging. Brand goes by the dubious name of Man han da can (滿漢大餐), literally “Manchurian-Chinese Feast”.

Ingredients mixed in bowl

Final product. Real meat!

I have a deep and abiding love for spicy food while being simultaneously extremely sensitive to it. I think of the pain and pleasure, the ecstasy and the agony of eating spicy food as a profound, even aesthetically sublime experience. Maybe something akin to “experienc[ing] [one’s] own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order,” which is something Walter Benjamin said about fascism, but which I also find to be true of eating spicy food. However, I suspect that the staff at the local eateries must think “What a weirdo” about this man who orders spicy food daily but is continually reduced to tears, snot, and gasping for air by even mildly spicy food.

Other things that help keep me awake come from poor living conditions. For example, although I live no longer live in a windowless box, as I once did, the opaque windows in my current apartment actually make it somewhat hard to distinguish between day and night. The showers in my last two apartments don’t provide hot water. Cold showers usually give me a burst of energy. Buildings in Taiwan usually don’t have indoor heating, making it very cold during the winters.

Textured glass windows, which seem to dull all sense of passing time

I also live above a major road, meaning that at all hours of the night there’s noise; my apartment vibrates when a large truck passes by. During the morning rush hour there are cars honking and traffic whooshing by. Since I live above a long stretch of road in a comparatively affluent part of town with a lot of nightlife, at night I might hear bar patrons arguing, the occasional bar fight, or the noise of cars or motorcycles illegally racing—rich kids who are Fast and the Furious wannabes, tearing around in expensive cars with tinted windows.

Whatever insomniac tendencies I had in the past became much worse after I moved to Taipei. Apart from the fact that one in five people in Taiwan has insomnia, it’s a city where there are always people awake, at any given time of night. Oftentimes I am one of them. It’s another way in which this city seems to be made for me.

Well, plenty of time to sleep when I’m dead, I always tell myself, as a distraction from the thought that not sleeping will shorten my lifespan, thereby undermining this whole enterprise of staving off the fear of death by not sleeping to begin with. But I simply can’t stand the thought of lying inert on a bed for 8 hours out of 24 per day. The thought of spending one-third of one’s existence lying on a bed is unbearable to me. I can never escape the equation that “SLEEP=DEATH” in my head, I’ve internalized it way too deeply to get away from now.