There are lots of reasons art doesn’t get finished. Buildings, too. A common reason is that the artist or architect dies. Or loses interest—they put aside the novel or canvas or play and don’t pick it up again. There can be other reasons too, particularly when it comes to buildings: zoning and planning wars; creative disagreements; the slow process of actually putting stone on stone or words to the page; an interrupted opium dream; money, money, money. For instance, one of the tallest buildings in Krakow, which has been a hovering skeletal shell since 1981, tangled and frozen in political, financial, and legal issues. Or Leonardo da Vinci’s “Adoration of the Magi;” he stopped midway through because he needed some cash and headed to Milan to curry favor with the duke who eventually commissioned “The Last Supper.” And that was that for the Magi—the painting remains a draft.

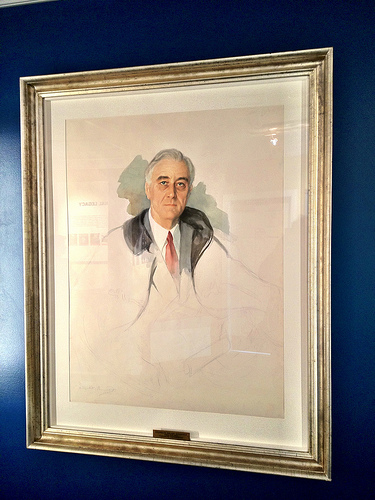

Sometimes, too, things are left “unfinished” intentionally, which creates some epistemological questions about what unfinished-ness actually is. Elizabeth Shoumatoff began painting a portrait of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1945. He was in good spirits, apparently doing an impression of Winston Churchill and making fun of Joseph Stalin (ha ha!). But then mid-portrait-sitting, he slumped over. He died right then, from a massive brain hemorrhage, with the painter in the room. Shoumatoff left the portrait as it was: his face and collar filled in, his body trailing out to outline, at once spectral and vivid.

She would go on to paint FDR again, a nearly identical replica that was completed, but it’s “The Unfinished Portrait” that’s famous. Indeed, an interesting thing about unfinished work is that it often generates more interest than finished work. Unfinished work is regularly the subject of bitter post-mortem disputes between artists’ estates and artists’ fans or family members—playwright Edward Albee’s unfinished plays will likely be litigated for years. (He wanted them destroyed; others would like to read what’s left of his work). This obsession with the leftovers and the incomplete is sort of weird, if you think about it, because there are millions—billions? A lot, in any case—of finished buildings and novels and symphonies and paintings and plays and poems and art, the broad category, for us humans to absorb. Why are we so obsessed with the ones that aren’t even done?

The answer, I think, is that unfinished-ness as a state often reveals both the limits and power of Great Artistic Dreams. Looking at La Sagrada Familia, perhaps the most famous Unfinished Building of all time, you can see both the outlines of Antoni Gaudí’s masterpiece, and the obstacles it has run up against. You can stand in the dappled orange-red-blue light of the perfect stained glass and marvel that a man could dream up such a place, and devote most of his life to that dream, and that it could come into being. Almost.

Construction on the cathedral began in 1882 and is still going, at a snail’s pace—it’s expected to be done in 2026 but don’t hold your breath; financial crises and political tensions can always intercede. Cranes hover over its spires, which will one day supposedly be the tallest of any church building in the world. The scaffolding is an undeniable blight on this holy shrine of stone and light. But looking at the cranes and the intricate façade, we can simultaneously see a grand vision and the ways it has failed because things got in the way: money, civil war, the death of a great artist.

Gaudí was hit by a tram when the cathedral was only a quarter of the way done; others have been attempting, over the course of more than a century, to fulfill his vision, which of course they can’t quite. Another architect got involved and designed it partly in a different style, to some controversy and some acclaim. The whole mishmash of what’s there today is moving; it’s sad and it’s wonderful to look at something that’s a monument to both the ephemerality and endurance of a great dream.

This is often why unfinished works are so appealing. Of course “Adoration of the Magi” would be a better painting if it were done. But would it be as interesting? As it is now we get to see what da Vinci wanted to do and what he didn’t do. It’s a chance to see a great mind at work, in progress, in media res, but it’s also humanizing; he too had money troubles, he too ran out of time.

Unfinished work—what happens to it after an artists’ death—has often been the subject of great disputes, as it is with Albee. Many artists want their unfinished works destroyed. Nabokov wanted his unfinished novel burned. Kafka wanted his unfinished manuscripts destroyed, including The Trial. I once wrote about the popular fantasy novelist, Terry Pratchett, who wanted a hard drive of his unfinished books crushed with a steam-roller after his death. His wish was actually carried out, unlike Kafka or Nabokov’s. Nabokov’s son wouldn’t burn the manuscript for The Original of Laura, and now we have another novel, or rather, part of one.

I’m inclined to think artists are protective of their unfinished work because they want the public to view their art, especially their magnum opuses, as bulwarks against time; projects that have reached an end and stayed there, forever. This is one of the great myths of art and architecture, and an appealing one: the idea of something that “stands the test of time,” a piece that “will endure.” I put these phrases in quotation marks not because these things can’t be true—they can, and often are, which is how I’m sitting here in 2019 writing about da Vinci. But they are also concepts that have become embedded in the process of creation, which can often drive artists a little mad. We have in our heads the concept of a finished “masterpiece,” rather than something that someone stops working on at some point in time for a complicated set of reasons, or just because they think, at some point, this is enough.

Unfinished works expose not only the mechanics of artistic process, but some realities that are both sad and freeing: art cannot actually stand outside of money, or politics, or time.