My first taste of the Han Kuo-yu era came the night after elections, when a friend took the high-speed rail up to Taipei from Kaohsiung and sought me out for drinks. He couldn’t stand the atmosphere anymore, he said, and had to get out of the city. I was a bit surprised then that he’d make a trip from one end of Taiwan to the other; in retrospect, I understand his decision better.

Since his election victory last November as mayor of southern Taiwan’s major metropolis, Kaohsiung, Han has been the focus of television coverage around the clock. A decidedly Trumpian figure, Han’s key characteristics are tough talk, together with an inability to fulfill any of his campaign promises. Nonetheless he has become a media phenomenon, the object of frenzied, even cult-like adulation from his supporters.

Han served for close to ten years as a legislator in the 1990s, but managed to convince voters that he was not your average politician. Instead, he campaigned as more of a “businessman,” since from 2012-17 he’d served as general chairman of the Taipei Agricultural Products Marketing Corporation, a partially state-owned enterprise for distributing agricultural products.

Despite his many gaffes, Han’s blunt, frank speech was seen as a positive, breaking from the political mold. He made highly misogynistic public statements, such as “a mature woman is like a bowl of soup—drink quickly once it’s cooked, otherwise it will burn.” His organized crime connections from his past political and business career were well-known. Heck. Han had even been involved in a fatal car crash, in which he was charged with manslaughter, though this only emerged after elections. But none of these things appeared to matter to his voters.

The strangest thing about Han’s victory is that he was an outsider to Kaohsiung; he had moved to the city simply in order to run in mayoral elections. While this is far from unheard-of in Taiwan, Kaohsiung voters chose Han over Chen Chi-mai of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), who grew up in Kaohsiung and campaigned as a native son. Chen proved in mayoral debates to have a strong memory for facts about Kaohsiung and was able to rattle off a seemingly endless number of concrete policy proposals off the top of his head, whereas Han sometimes seemed at a loss for what to say entirely and lacked knowledge about even his own neighborhood.

It may be that Chen was simply too lacking in charisma; he came across as nerdy and wonkish, whereas Han projected a relatively attractive bad-boy image. Having watched a few more kitschy Japanese romance dramas than I care to admit, the campaign reminded me of the romance drama trope in which the (usually female) main character has to pick between the loyal, nerdy childhood friend, and the dangerous but alluring bad boy. It’s very rare to see any drama’s protagonist go for the former. So, too, perhaps, with the Kaohsiung electorate.

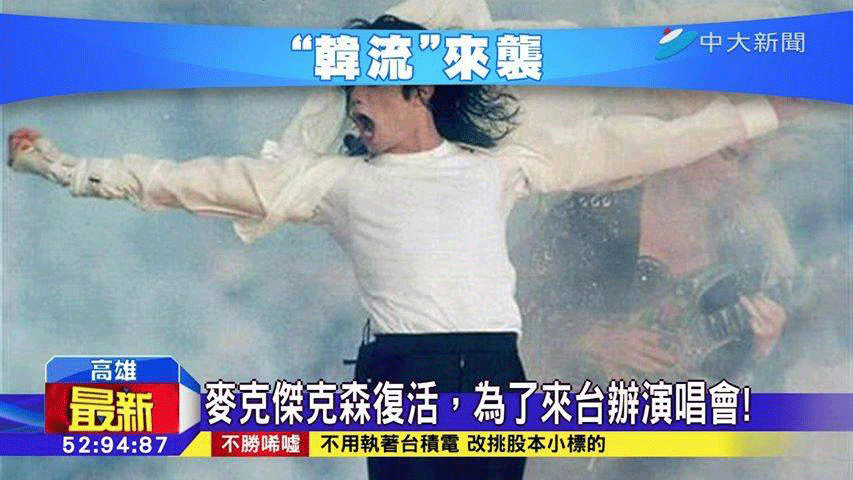

The Han phenomenon is often referred to as the “Han wave”. He also acquired the rather odd nickname of “Korean fish,” because his surname and the first character of his given name (“Han” or 韓 and “Kuo” 國) when combined means “Korea” (韓國) and the second character of his given name (“Yu” or 瑜) is a homonym for “fish” (also “Yu” or 魚).

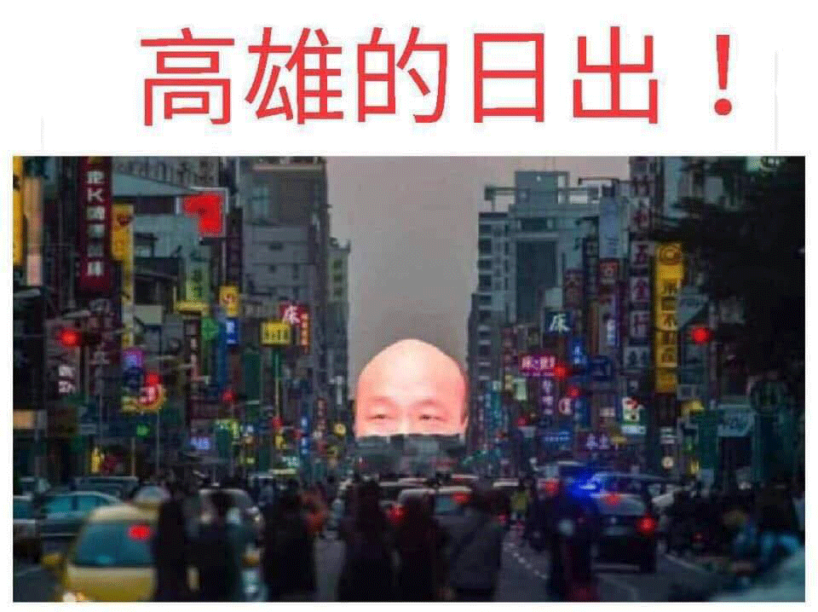

This nickname was originally used by Han’s critics, but eventually his supporters adopted it too. At campaign rallies last year, you‘d see Han supporters carrying images of fish and the South Korean flag. Critics of the constant coverage have sometimes joked that Han’s media omnipresence has become “North Korea-like”. But, well, the Korean fish is here to stay.

Among Han’s more colorful campaign promises were that he would bring F1 racing, world-class horse racing, casinos, Disneyland, and… a visit by Arnold Schwarzenegger to Kaohsiung. He also claimed that he would increase the city’s population to five million and revitalize the economy by drilling for oil in the South China Seas. All this, in four years in office!

It should go without saying that most if not all of these promises will be impossible to deliver. Gambling is illegal in Taiwan, with casino construction legally permitted only on the outlying islands—yet no casinos have been built to date, in the face of popular opposition. Sports car and horse racing are also illegal in Taiwan, leaving aside the fact that Han proposed that his horse race track be built on what was originally an oil facility; clean-up of this facility will take until 2033, presumably well after Han leaves office. Disney theme parks require years of planning and investment, with goals announced many years in advance; there’s been no indication that the company has set its sights on Taiwan.

Increasing Kaohsiung’s population to 5 million would require nearly doubling the population of the city—already Taiwan’s second-largest—within four years. And drilling for oil in the waters of the South China Seas—disputed territory between Taiwan, China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia—sounds like a pretty good way to start a world war!

Han’s outlandish campaign promises reflect his personality perfectly. He likes big, fast, flashy things, hence the notion of constructing an F1 race track or a horse race track. I have no idea who would really care if Arnold Schwarzenegger were to visit Taiwan—he would probably get more mileage out of inviting, I don’t know, Justin Bieber. Maybe Han just really likes the Governator.

But his fans really do not seem to realize or care that much of what Han says is nonsense. When will the Han bubble burst? Will the damage be irreparable, by that time?

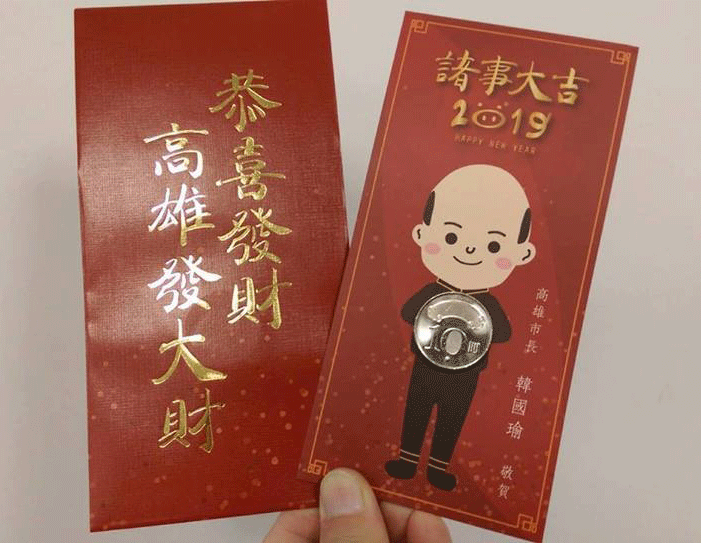

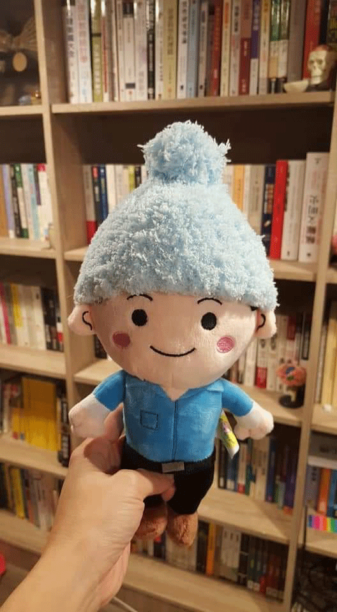

The thing that truly blows my mind about the Han personality cult, however, is the veritable cottage industry of Han products that have appeared since last November. There are expensive designer handbags, red envelopes (in China and Taiwan, it is considered polite to give money in red envelopes), gashapon capsule toys, dolls, and many other items featuring his image. Quotes made iconic by Han, such as “Goods out, money in” (貨出來,錢進來) are also featured on products. It’s hard to believe that companies would invest the resources in designing and producing such goods, hoping to cash in on the Han craze.

Photo credit: 高雄迷因 Kaohsiung meme/Facebook

Photo credit: 高雄迷因 Kaohsiung meme/Facebook

韓國瑜粉絲後援會/Facebook

韓國瑜粉絲後援會/Facebook There are even entire Han-themed stores, including a Han hot pot store and a wig store (Han is bald).

The rise of Han has contributed to a growing sense of helplessness among many young people, who see Han as the sign of a resurgent Kuomintang. After the battering the Kuomintang received in the 2016 elections, the Kuomintang has been desperately searching for a way to win the support of young people, who have been alienated by Kuomintang policies aimed at facilitating the unification of Taiwan and China, as well as policies benefiting financial elites and entrenched interest groups at the expense of other strata of society.

The Kuomintang’s pursuit of younger supporters has generally failed. I myself have done no shortage of scoffing at their ridiculous attempts to conduct outreach with young people.

But the Kuomintang finally has the charismatic figure it needs to rebrand itself in the form of Han. Even if the Kuomintang remains as ridiculous as ever, voters seem to like it!

For more left-wing and pro-independence young people like myself, the recent election results caused a lot of soul-searching. Just as the Han personality cult grew into this odd microcosm of the Internet devoted to adoring him, a mirror image grew on social media devoted to scoffing at Han with ridiculous Han consumer products to mock, or news articles about his failures to tear into with great schadenfreude. The schlocky lanterns that Kaohsiung displayed at this year’s Lantern Festival, were mocked in this way, including several depicting Han himself.

But mock all we want, there are enormous numbers of people who are diehard Han fans, including young people. I don’t have blind faith that the Han bubble will suddenly implode and people will wake up and smell the roses.

We’ve seen how Trump supporters will still back him to the hilt in spite of his obvious hypocrisy, or Brexit supporters still convinced that Brexit won’t have any negative effects. The highly polarized news environment, in which each side reports only on news favorable to themselves and unfavorable to opponents, exacerbates these tendencies.

There’s a lot of talk now of the need to break out of social media echo chambers and self-selecting peer groups, particularly to dialogue with older people. Just as in the United States there is a lot of talk about how to dialogue with the working class, following the assumption that it was mainly working-class voters that voted Trump into office. Amusingly, this effort involves attempts to communicate with the elderly through so-called “zhangbeitu” (長輩圖), or “elderly images,” a type of meme which older people like to send around.

There’s a strong tradition of personality politics in Taiwan, with politicians developing cult-like followings. Han’s predecessor, Chen Chu of the DPP, was such a figure. Her history as a democracy activist during the martial law period added to her cult appeal.

Yet just as Kaohsiung suddenly reverted to Kuomintang control in 2018, after decades of DPP control, these personality cults can evaporate into nothing overnight. Such figures as rise to prominence through the media, may also be torn down by the media just as abruptly.

Maybe this is the early stages of a right-wing populist wave in Taiwan, part of the global resurgence of the right that led to Brexit, and the rise of Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, and other authoritarians. Or Han’s sudden rise to superstardom might, in the long run, turn out to have been a flash in the pan.