It’s hard to not to have a love/hate relationship with the underground party scene in Taipei. Sure, you’ll meet a lot of strange and interesting people; I can’t deny that it all feels very fun in the moment, on the dance floor. But there are maybe just too many crazy people out there. I’ve gotten a bit tired of hearing about Elon Musk discovering that we all live in the Matrix and how—great man that he is—he plans to break us out of simulated reality with lasers.

I used to be the guy who always stood stock still on the dance floor on the odd occasion I found myself in a club, but in time I became part of the nebulous entity we might refer to as the “Taipei underground,” largely through Korner, an underground techno club that closed last year. Korner was the nighttime alter ego of The Wall, Taiwan’s premier indie venue. The first time I went to Korner in 2013, with a group of strangers from a school gathering, I drank so much that I ended up falling down a set of stairs and knocking out a tooth. I had to have a dental implant, which meant drilling a screw into where my tooth had been, and screwing in a fake tooth. So I guess I’m technically a cyborg now, thanks to Korner.

Bad things tend to happen to me when I go partying. For the past two and a half months my left knee has been wonky, after a friend of mine tried to jump out of a moving car on a highway while we were heading back from a queer art party in a taxi; I twisted my knee grabbing her as she was rolling out of the car. But I discovered the underground electronic music scene in Taipei as a result, so maybe the injuries were worth it.

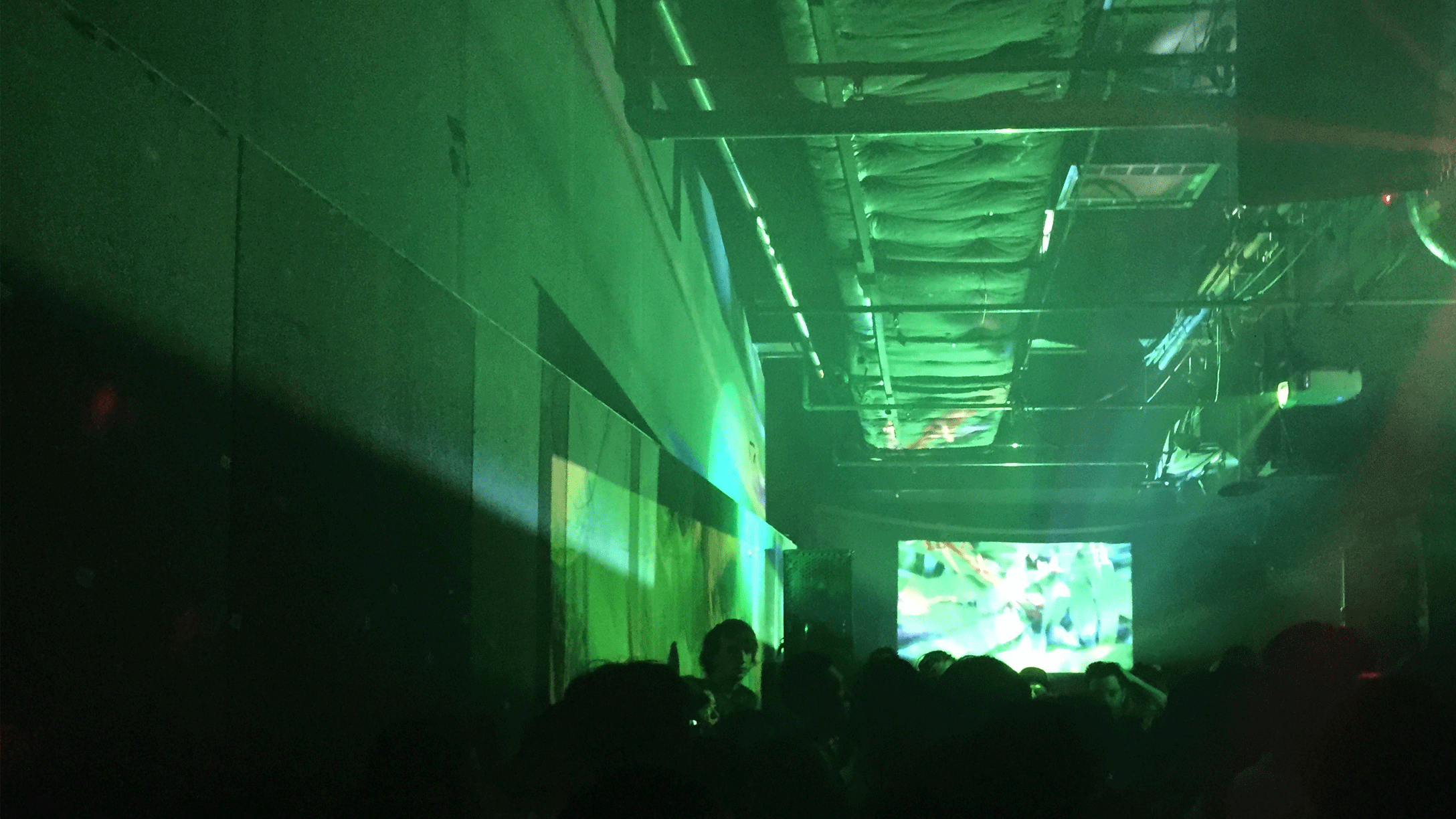

For a long time, Korner was probably Taiwan’s only internationally known underground electronic music club. The cool thing about it was that they allowed artists to do installation art to change up the space for parties. Technically “Korner” was the name of the main space (which, during the daytime, served as the corridor of The Wall) where featured acts played, with generally more danceable music. “Outer,” the secondary room, became a place for less danceable, slower, or more experimental fare. For the biggest events, they would open up the “The Wall” itself, the largest space in the building.

Korner would have something going on Friday and Saturday, as well as some Wednesdays. There would be a crowd of people gathered outside of the entrance, smoking, those looking to save money drinking Taiwan Beers from from a convenience store five minutes’ walk away.

Right before it closed, Korner’s parties were going in innovative directions, breaking down the barriers between live bands and electronic music; once, after a performance by the indie band Forests, stage hands carried out DJ equipment midsong, set it up, and Forests lead singer Jon Du began DJing uninterrupted.

Nobody really knows why Korner closed—or at least, I’m too much of an outsider to know. It certainly wasn’t for lack of business.

I’ve also heard rumors that the staff were unhappy with how things were being run, and that there had been some beef between the owners of The Wall/Korner and some well-known indie bands. The main organizers, I’ve heard it said, had a blacklist, which excluded some figures who’d played a significant role in the development of the underground scene over the past ten years. You can’t run a space like that without accumulating some grudges, perhaps.

And then some thought that Korner had become cooler than thou. It was hard to go there without feeling uncool, as if you weren’t as chic or edgy as everyone else. I thought some of the parties were becoming a bit too over-aestheticized, with too much of an emphasis on abstract conceptualism or deliberate shock value, such as playing up this sort of Berlin sex party aesthetic for events which turned out, in the event, to be fairly tame.

Korner also took some heat for the high prices imposed when famous foreign DJs were invited to perform—higher ticket prices required to pay for the stars’ travel to Taiwan. By contrast, local Taiwanese DJs seemed always confined to the peripheries of Outer, which led to some grumbling. Nearly every week some big name DJ would be playing, and so prices always seemed high. Since Korner closed, prices for underground club events have generally dropped. Yet there may be fewer big-name DJs coming to Taiwan, now that Taiwan no longer has an internationally-known club.

I think that this reflects a few things. Electronic music has long been a feature of the Taiwanese musical landscape, as observed in something like the working-class “taike” (台客) techno of the 1990s and 2000s. “Taike” is a derogatory term for working-class “benshengren” Taiwanese, descended from the 90% of the ethnic Han population which had been living in Taiwan for hundreds of years before the Kuomintang came to Taiwan after its defeat in the Chinese Civil War. Taike techno might be best known internationally for giving rise to the internationally famous Electro-Techno Neon Gods, in which techno was combined with temple ceremonies; many young temple dancers went clubbing on the weekends, and thus ended up combining their musical tastes with temple ceremonies.

But clubs are generally seen as dangerous by Taiwanese society, as dens of corruption and iniquity due to the drug usage that sometimes goes on there, or the association of some nightclubs with organized crime. This leads to periodic attempts by politicians to crack down on clubs as a way to score political points, say, when there is a large drug bust or overdose widely reported on in the media, or after fights taking place outside of clubs.

Such attitudes reveal the highly conservative underbelly of Taiwanese society. Taiwan’s draconian drug policy, for example, treats even marijuana as a highly dangerous drug. This has unfortunately led it to become one, as we saw in a murder case last year when a group of expat marijuana dealers decided to kill one off their own, whom they’d suspected was a police informant.

Even so, Taiwanese politicians periodically throw parties in order to attract votes from young people, as recently observed in the Nuit Blanche events thrown by current Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je, Tainan fringe mayoral candidate Mark Lin’s “Crazy Friday” campaign, or the raves that former president Chen Shui-bian threw around the turn of the millennium, back when he was Taipei mayor. Somehow, the Electro-Techno Neon Gods now travel around the world to perform in Taiwanese cultural events, despite that the group’s style of electronic music was originally associated with organized crime.

The partial stigmatization of clubs or partying almost guarantees that the young people who go to these places deliberately embrace a subversive image. You get a lot of people wearing all black, or who are all spikes and tattoos. However, it strikes me as being a sort play-acting sometimes, like cosplay.

It could just be that I’m a normie. Part of why I never really felt I completely fit into party culture was that, despite my generally dissolute lifestyle, as a journalist, I still work in a profession that requires me to blend into white collar society during the day. But it seems clear as well that at a certain point in the past two decades, techno aficionados began seeking cultural respectability or cultural capital. It could no longer be about just having fun—it had to also be thought of as sophisticated.

The global mainstream popularity of the genre of electronic music known as Electronic Dance Music (EDM) has made fans of underground electronic music all the more anxious to distinguish themselves from what they view as crass, philistine sounds. Even the term EDM is highly misleading, often used as a catch-all term for all electronic dance music, when it is in fact a specific genre with certain defining characteristics, just as techno, house, trance, psytrance, and disco, are genres of electronic music.

This longing for respectability has its roots, perhaps, in the low regard in which electronic music is generally held; the mainstream view being that electronic music producers and DJs are just pushing buttons, which is thought to require no skill or talent.

Bands or solo instrumental artists are seen, by contrast, as authors and creators, who require years of training and practice to play their instruments—as though this were not also true of electronic musicians—and respected accordingly.

Since the issue of training is often raised by people playing in bands, I tend to reply, as one with decades of training as a classical musician, that one could easily make the same complaints about them.

This is one reason I find acts that can’t really be classified as strictly electronic music production or strictly as bands so exciting. In Taiwan, a few examples I like are Prairie WWWW—which has something of a cult following—Forests, and Mong Tong.

Anyway, since Korner closed, a bunch of new spaces have opened. Some were opened by former party organizers who threw parties at Korner. Others I’m pretty sure are just run by mainstream club owners who realized that there’s a buck to be made from the growth of the underground scene in Taipei.

The so-called underground never really escapes market forces. This is despite the claims to radicality of some prominent underground electronic music groups, or underground party scenemakers who view their scene as a space apart from capitalist oppression. At the end of the day, whether in terms of mainstream clubs or underground clubs and parties, most people are just there to blow off steam from the workweek and spend some money on beers and fun.

Heck, that’s really why I go to all these parties myself. Most will really just dance to anything, and don’t care much about underground or radical culture. It seems like just a form of radical chic, a fixation on superficial appearances more than anything else. Just a style.

Just as many are out to get wasted, high, or drugged out—as we say in Taiwanese, kiang (狂)—and nothing wrong with getting kiang. For all the paranoia about drugs in Taiwan, society would probably be a lot safer if drugs were legalized. But anything sounds good after you’re kiang. It’s hard to expect a discerning musical—or political—taste after that.

Next in Tempo: Me Today by Erin Schwartz, on the Jersey Shore