I take Nate Powell’s “About Face: Death and surrender to power in the clothing of men”—which warns of the appropriation of a “military style” that caters to “aggrieved white Americans with an exaggerated sense of sovereignty”—very seriously. As a historian, and a former howitzer gunner and senior jumpmaster in the 82nd Airborne Division, I find the militarization of civil society just as troubling as he does. But it’s important that we be crystal clear about how dramatically the “military style” Powell describes departs from its origins and purpose within the military itself.

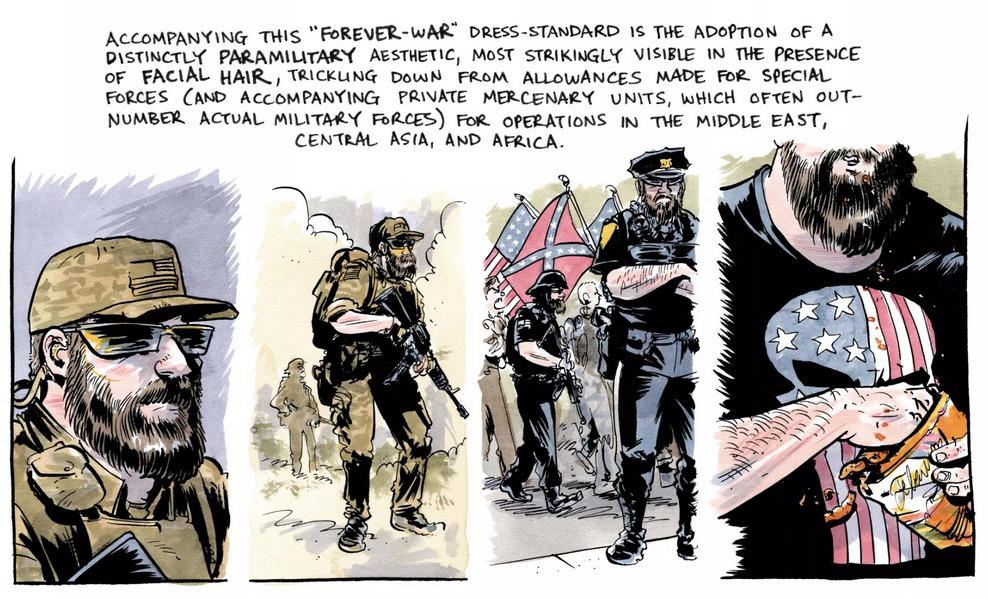

Powell’s ultimate conclusions regarding the malignancy of a “military style,” appropriated along hyper-masculine, hyper-nationalist, and highly commodified lines in American civil society, are correct. But Powell’s analysis erroneously refers to the same cultural zeitgeist to explain both military conventions, and the civilian appropriation of the “military style.” Treating both as manifestations of the same overarching culture effectively ignores the material concerns that distinguish the military’s appearance and design standards from the “future fascist paramilitary participants” Powell rightly warns us about.

At the outset of his piece, Powell characterizes service members’ everyday wear of “combat fatigues” as the indulgence of “a stunted child’s play-acting fantasy,” creating what he dubs a “forever war dress standard.” Aside from demeaning the men and women who serve in America’s armed forces, that description is both reductive and ahistorical. In reality, the wearing of fatigues for everyday garrison duty is nothing new, and is certainly not, as Powell suggests, a dramatic change that took place in just a single generation.

Prior to WWII, the U.S. Army’s service uniform was the field uniform (start from about p. 75 to cover modern history). That started to change when the introduction of the field jacket in 1940 relegated the old service coat to the garrison. Then the adoption of the “pink and greens” service uniform created even more separation between field and garrison wear. It was a separation that gave way following the Korean War, and by the 1960s and 70s the all-green utility fatigues and cap were everyday work clothes for most soldiers in garrison, though certainly not all. Powell’s images (and the artwork in this piece is brilliant, by the way) depict soldiers doing what appears to be clerical work, but many offices in a military setting require the wear of the Class B service uniforms, which consists of the Army blue trousers and a white short-sleeved dress shirt (or long-sleeved with a tie) with the appropriate accoutrements. This is typical attire, for instance, in administrative offices in headquarters units, military in-processing units, and recruiting offices.

More to the point, what should service members wear when going about their everyday jobs? For those who serve in Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) categories that are more administrative or clerical, Class B service uniforms might work fine. However, 71 percent of active duty soldiers serve in just five areas: transportation and material handling, mechanic, engineer, electrical equipment repair, and combat arms, which alone accounts for nearly 30 percent of U.S. Army personnel. Uniform options other than “fatigues,” like the Class Bs, require crisp white dress shirts and the painstaking placement of ribbons, insignia, badges, nametags, ranks, and epaulettes. They are the equivalent of civilian professional attire one might find in a bank or accounting office, and are thus ill-suited to the jobs that more than two-thirds of soldiers do on a daily basis. No one expects a mechanic to wear a dress suit to the garage.

“About Face” is even less precise in the matter of beards; they are first described as part of a “paramilitary aesthetic” emanating from specific allowances granted to Special Forces operators, as well as among the private contractors who have become disturbingly more prevalent in recent years. But keep in mind that allowances for Special Forces operators were made specifically in order to allow those operators to conduct their work without drawing attention to themselves as military.

The allowances made for Special Forces operators are not new, nor do they extend to the rest of the regular army, with one exception. Since 2009, the Army granted Sikh soldiers a religious exemption, so that they could keep their beards. In early 2017, the Army authorized a new directive that made those exemptions a regular policy (and it also applied to turbans, as well as head scarfs or hijabs for practicing Muslim female soldiers).

Beards are explicity and fundamentally part of a civilian aesthetic, not a military one, save for an extremely small number of special operators, and soldiers requiring religious accommodations. Employing a civilian aesthetic adopted by select members of the military to explain the civilian adoption of a military aesthetic that was itself an adoption of civilian aesthetic—whew! That’s convoluted.

The military appropriation of a “civilian style” is not limited to beards, either. As Powell notes, the Department of Defense has partnered with car manufacturers to design vehicles with interchangeable parts that can mimic civilian models. Powell is 100 percent correct that this move is made possible by an existing relationship, wherein manufacturers deliberately militarize some of their civilian lines. However, by referring to this as a “GI Joe inspired… toy store move,” Powell chooses snark over an honest assessment of the real-world material concerns that motivated special operators to request these vehicles.

Standard military vehicles are easily identifiable. Since we’ve already established that special operators often have to carry out their missions discreetly, a HMMWV is probably not the best choice. Standard issue vehicles are also easy targets, which means a person employing an IED against American soldiers has plenty of time to recognize the vehicle and time an attack. By contrast, a vehicle made to look like a Nissan pickup is just one in a sea of other Nissan pickups. By the time a would-be-attacker might notice that the driver looks like an American, the vehicle has likely passed safely.

My criticisms here should not detract from Powell’s larger point, which is valid, and worthy of attention. But this is about more than mere nitpicking. When white nationalists march in the open in public, in Charlottesville or elsewhere, donning tactical gear and carrying military-style assault weapons, they are most definitely not an extension of the culture of the US military; they are a bastardized and perverted version of it.

They’re not wearing wrap-around sunglasses because they are operating in a windy, sandy, and extremely bright environment. They don’t wear tactical gear or ballistic vests because they might legitimately find themselves in a firefight.

They are the real play-actors, not the service men and women who wear “fatigues” because they spend most days training in the field, or because they’re in the motor pool, cleaning, repairing, and maintaining their equipment. The 1,600 military amputees since 2001 whose vehicles were so easily targeted with IEDs are not play-acting, and a desire for vehicles that are not easy targets is not some G.I. Joe toy fantasy. The scores of active duty and veterans who suffer from traumatic brain injury, anxiety, and PTSD are not play-acting. The twenty-two veterans who take their own lives each and every day are not play-acting.

There are many service members and veterans, myself included, who are uncomfortable with the various ways that civil society has been militarized, from the entanglements between sports and the military to the weapons of war found in American streets. Their voices are important in our discourse because they carry the weight of credibility. They are difficult to dismiss, especially for those who fetishize the military. Yet, criticisms of the “military style” that mischaracterize the military create a space for people to flippantly dismiss valid criticisms of militarization as just more political posturing, even when those criticisms come from military veterans.

I hope that Mr. Powell would agree that we want to encourage people like General Stanley McChrystal, who has criticized weapons of war on American streets, to ally themselves with those of us who share similar concerns about a militarized civil society. Reductive characterizations that imply that our service members and these malignant proto-fascists are essentially cut from the same cloth are counterproductive. We can do better than that. If we want to take the issue seriously, then we have to make the correct distinctions between these groups of individuals. Only then can we properly de-normalize the power fetish embedded in the dangerously perverted articulation of the “military style.”