A year or two ago outside a Taipei bar, I got into an argument with a friend—like me, a lifelong New Yorker—about Andrew Yang, who was then a presidential candidate.

My friend said he related to Yang; he saw something of the common man in him. Heck. He spent a bit of time every day watching videos of Yang, he told me. I guess he found it therapeutic.

WHY? I demanded.

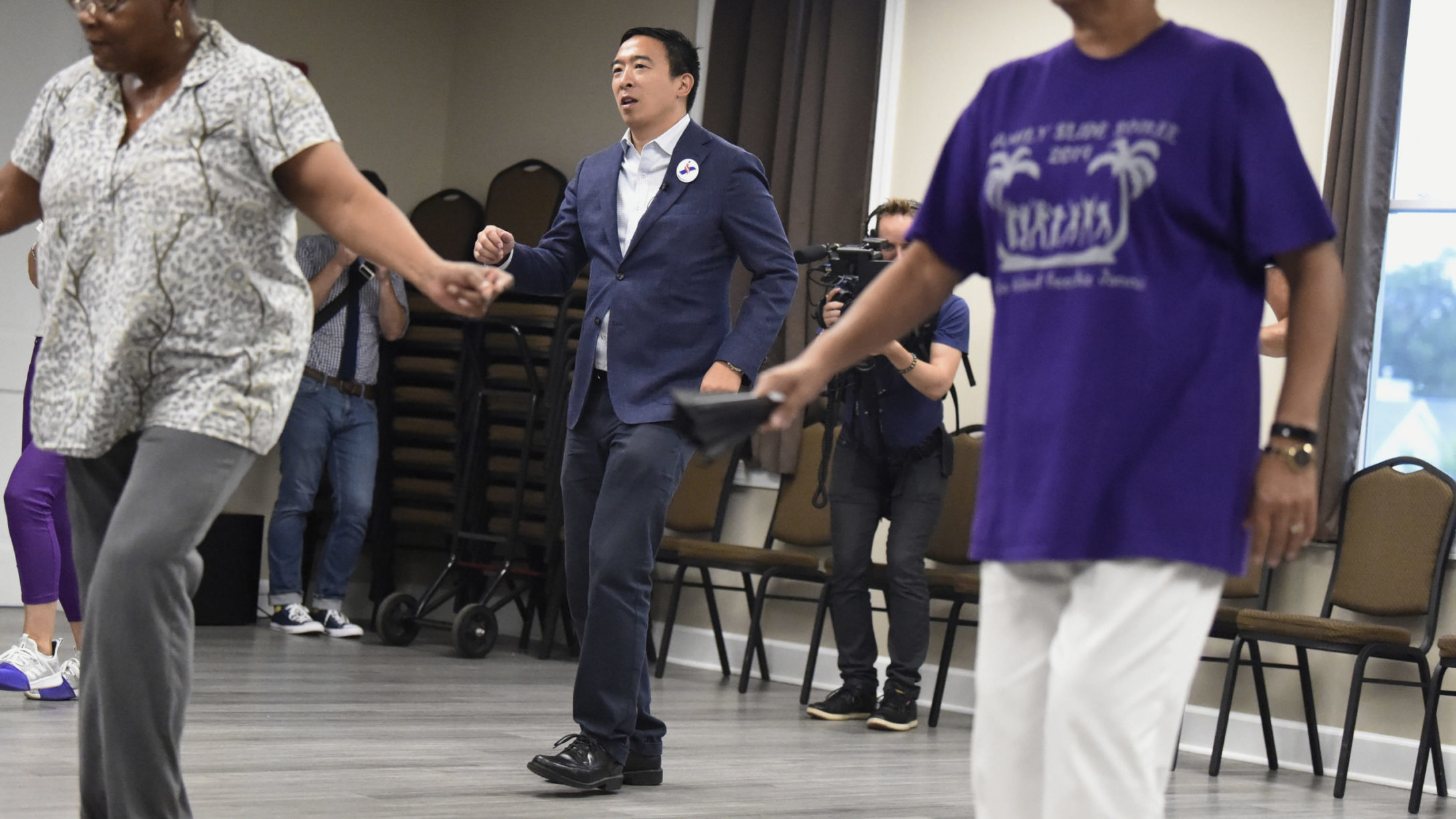

I saw precisely the opposite. Looking into Yang’s eyes, I saw… nothing. The video of him dancing the Cupid Shuffle during a campaign stop reminded me of Dennis Hopper in Blue Velvet, lip-synching to Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams” as Kyle MacLachlan stares at him in wide-eyed horror. But people seemed to just eat it up, a sign of how Yang was a regular Joe—prone to doing silly things, not always trying to look slick in front of the camera. The viral Cupid Shuffle video racked up well over a million hits. I couldn’t understand this in the slightest.

I find Yang simplistic and vacuous. The most deeply unsettling thing about him is that he seems to stand for nothing at all, allowing voters to project whatever they want onto his empty smiles.

Veteran political consultant Bradley Tusk agrees. Ben Smith in the New York Times yesterday reported that many of Yang’s campaign staffers work for Tusk, a former consultant to Michael Bloomberg, Rod Blagojevich, and Uber.

Mr. Tusk told me in an unguarded moment in March that Mr. Yang’s great advantage was that he came to local politics as an “empty vessel,” free of fixed views on city policy or set alliances. When I asked the candidate what he made of that remark, Mr. Yang took no offense. “A lot of New Yorkers are excited about someone who will come in and just try to figure out, like what the best approach to a particular problem is, like free of a series of obligations to existing special interests,” he said.

Yang first became famous for popularizing the idea of Universal Basic Income (UBI). I had the feeling then that people just loved him because he offered the promise of magic money from space to solve all of their problems, with many failing to realize that his offer of UBI was a front for a program of paring back government services—justifying neoliberal reforms with progressive reasoning.

Unfortunately, Yang’s political career grew beyond his championship of UBI. All this gives me a terrible feeling that he will, in fact, unexpectedly become the next mayor of New York City, just as few expected that Donald Trump would become president in 2016. Voters once found Trump, too, appealingly different from his smooth, polished political rivals, and felt that he too could relate to the common man. Yet it was (and still is) common to learn that Trump voters couldn’t name their favored candidate’s policies, and were surprised to learn his true political stances. So, too, I find, with a lot of Yang supporters. Did you know, for example, about Yang’s bizarre anti-circumcision platform?

The rise of Andrew Yang comes at an ironic time, at a time in which Asian Americans have faced unprecedented hatred and violence because of the COVID-19 pandemic, with nearly 4,000 attacks reported at Stop AAPI Hate.

In this context, the election of an Asian American mayor in New York City would send a powerful message. But then we remember that this is a man who didn’t want to state in public that he was from Taiwan, choosing instead to refer to himself as being descended from peanut farmers from Asia.

Maybe Yang fears to offend someone by claiming his Taiwanese heritage. Or he may be keeping his origins vague in order to appeal to as large a swath of Asian America as possible, while still playing into notions of hardworking immigrant ancestors who managed to make it to the US after a brutal life elsewhere, portraying Asia as a dark, scary and barbaric place. This political breeziness, like Trump’s, will come with real-life consequences.

Members of the Stonewall Democratic Club of New York City were offended by Yang’s condescending references to “your community” in a widely reported meeting; he went so far as to tell the membership of New York’s leading LGBT group that they were “so human.” as if there were a scale of humanity. Yang appeared unable to step beyond his own identity and, in trying to come off as “harmless”, just evidenced his insincerity and incoherence—heck, Yang has even tried to defend not living in New York City and instead living in New Paltz, yet running for mayor of the city. A campaign promise of Yang’s is that TikTok Hype Houses are the form of public infrastructure that would benefit New York City.

Yang has been criticized throughout the course of his political career for feeding into Asian stereotypes, while seemingly fearing to offend. The cringe-worthy quotes keep right on coming—“Now, I am Asian, so I know a lot of doctors,” “Well, I’m Asian, so you know I love to work,” or describing himself as “the Asian man who likes math.” He peppers his talks with Asian stereotypes in a playful manner, in hopes that white America and the powers that be will view him as non-threatening, rather than winning people over on the strength of his message. When Yang does try to break from the mold, it comes off as insincere and ridiculous—as when he claimed he’d be the first “ex-Goth president” of the US during his 2020 presidential campaign.

This superficiality explains much of Andrew Yang’s relation to “bro culture” as well. A toxic work environment for women—including a reported payment of $6,000 to a female staffer, to settle her discrimination claims—was described by staffers as an atmosphere of “bros who promote bros.” Public comments by Yang often come off more frat boy more than anything else—for example, he stated in public that he named his two pecs “Lex and Rex,” and he recently came under fire for laughing after he was asked (by a man) if he choked women.

Yang has made his political career by trying to please everyone. That is a failure of leadership. His proposed solution to anti-Asian violence is to increase funding to the police, with the aim of increasing the number of Asian American police, or even to turn the other cheek, to “show our Americanness” against xenophobes. He represents the logical outcome of the model minority myth—never going against the status quo, and always working to appear harmless, in hopes that the powers that be will throw you a bone. Yang is the very antithesis of what Asian America needs from its leaders at a time of crisis, when powerful voices must take a stand against anti-Asian racism and other forms of racism in the US. That probably won’t prevent many from voting for him, though. At this point, terrible and vaguely sociopathic mayors seem to be a New York City tradition.