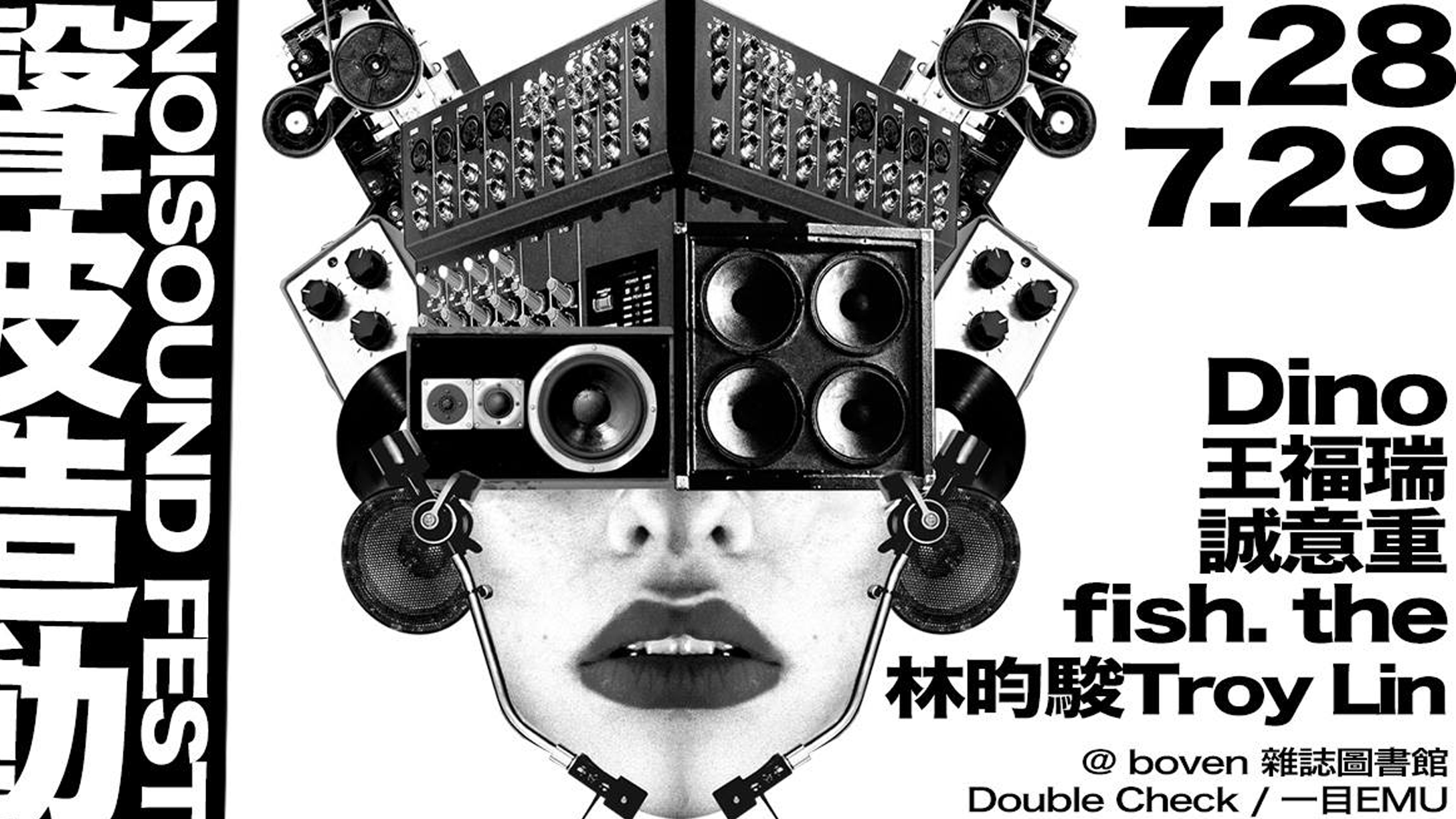

July 29, 2018

Taipei, Taiwan

I went with my partner, L., plus several friends, to the second day of the two-day Noisound Festival, which was from two p.m. to five p.m. It felt strange to attend a noise performance that didn’t take place at night. I thought that hearing three hours of noise music performances about an hour after I got up would wake me up, but it didn’t.

Some us started drinking, which felt normal for a noise performance, but I thought I would fall asleep if I did. I have a policy of not drinking before six p.m., since I usually tend to fall asleep a few hours after drinking. But I couldn’t do that, seeing as I had just gotten up. Plus I was already tired. L. and I had stayed up until 6:30 a.m., binge-watching shows.

I almost did fall asleep, somehow, not that I didn’t enjoy the music. It was a nice, small gathering. The summers are usually quite good for noise in Taipei. I had attended, what—three noise performances in the last two weeks?

I’ll probably remember this one the most clearly, though. Sometimes I wonder what the point of attending a musical performance is when you drink enough that you don’t actually have the clearest memory of what you heard. All you remember is that you had a good time or didn’t.

We didn’t stick around after, although some of our friends went out to dinner. I wanted to go watch a screening of 抗命者 (“Those Who Resist”) outside the Legislative Yuan, Taiwan’s legislature.

抗命者 was the newest documentary on the Sunflower Movement, specifically detailing the role of the Alliance of Referendum for Taiwan (ART) in the movement, which had maintained a continuous occupation outside the Legislative Yuan for something like ten years to push for a referendum on Taiwanese independence. I maintain a sourcebook in the online oral history archive and encyclopedia for the Sunflower Movement, so I felt I should go watch it, so that I could add it as an entry.

The documentary turned out to be almost exclusively about the first night of the occupation of the Legislative Yuan on March 18, 2014. It was nine hours of footage edited down to two, set to orchestral music which I thought was a bit unnecessary (Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 in D Minor, Shazam told me.)

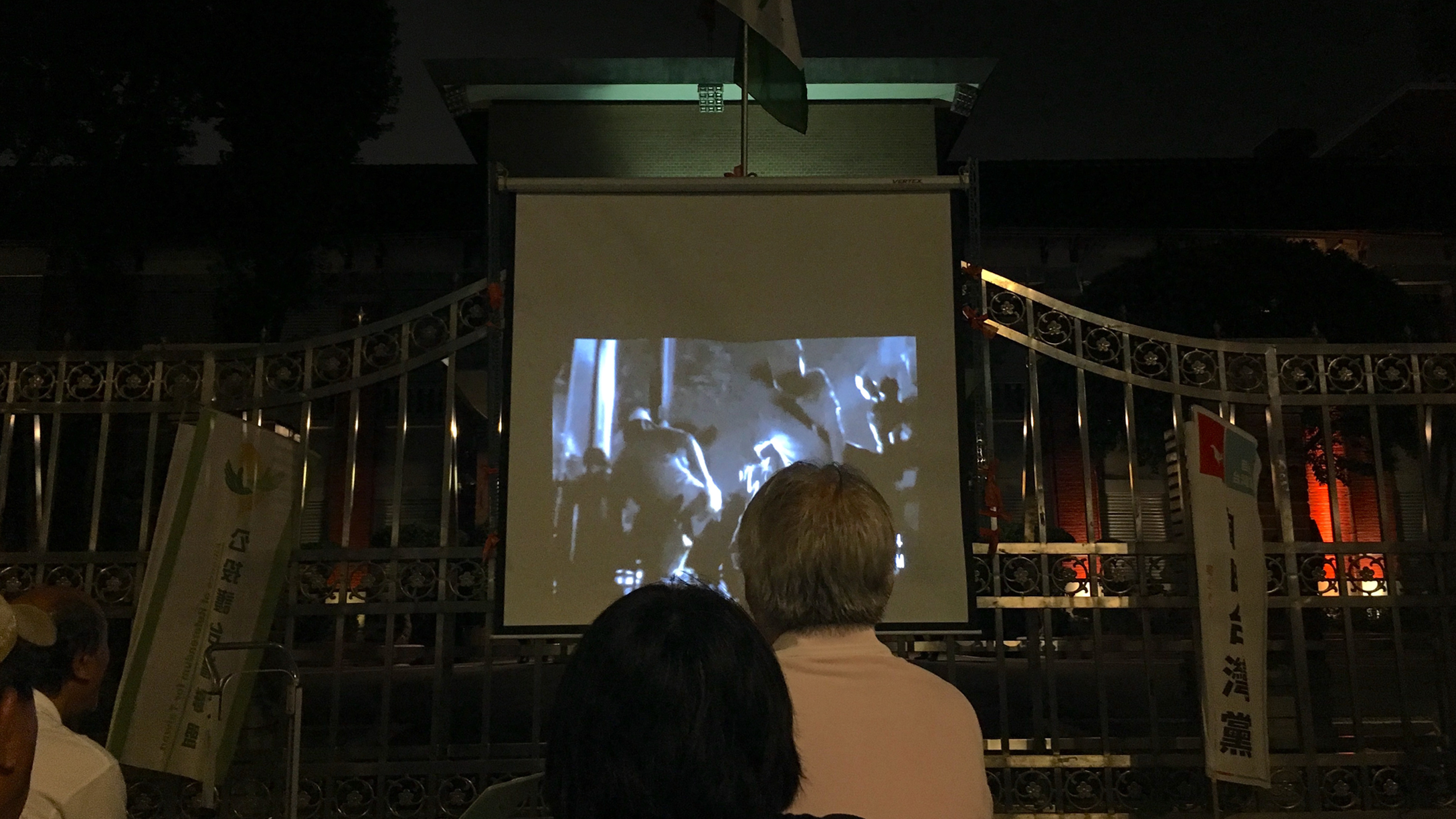

Photo: Brian Hioe

Photo: Brian HioeThe screen was affixed to the front gate of the Legislative Yuan, and the projector was placed on a stool. Probably, official permission had not been obtained for the screening; two dozen or so police officers from the Zhongzheng First Police Precinct kept a wary eye on the audience.

Ironically enough, the police were involved in their own form of documentary filmmaking, filming the crowd for the duration of the screening. This is standard practice for Taiwanese police during protests, as I also observed to be true of Japanese police when I studied there in college. Sometimes they use the footage as evidence in prosecuting protesters, but it mostly seems to be used for the purpose of intimidation—the police don’t seem to be paying too much attention to whether they are capturing clear footage or not.

It was rather strange watching the documentary right outside where the events had taken place in real life. In fact, some members of the crowd, which was around 40-50 people, were also visible in the documentary. As we stared at the film projected on the gate of the Legislative Yuan, watching documentary footage of events which had transpired on the other side of that same gate four years ago, it felt sort of like we were staring out at the ghosts of history—even if those ghosts were ourselves, from four years ago.

I myself was at the side gate that night, not at the front gate with the ART, as part of the crowd that eventually broke down and climbed across the fence surrounding the compound’s parking lot. So this was an opportunity to see what was going on at the other side of the Legislative Yuan at the beginning of the protest. I was a bit disappointed that the film only captured the events of the initial Legislative Yuan occupation, because the ART also played a key role in the storming of the Executive Yuan, Taiwan’s executive branch of government. While I had participated in charging the back door of the Executive Yuan, and knew that the ART had made an unexpected appearance during this charge, I did not see them firsthand, having been kettled by the police by then.

The film did a good job of showing not only the moments of sudden rupture in social movements, such as overt clashes with the police, but also the sheer monotony that can drag on from stalemates that last for hours and hours.

Flickr/ Tomscy 2000

Flickr/ Tomscy 2000On the way back to L.’s apartment, we got bubble tea from a place in front of the night market I pass every day, but had never tried. It was tieguanyin-flavored bubble tea, tieguanyin (鐵觀音) being some type of oolong tea; literally “Steel Guanyin,” after Guanyin, the goddess of mercy. I wondered aloud if that was where the film “Xieguanyin” (血觀音)–last year’s winner for best film at the Golden Horse Awards—had gotten its name. “Xieguanyin” means “Blood Guanyin.”

There was the phrase, “blood and steel,” after all. And it sounds similar in Chinese. The film is also known by the somewhat awkward English title, “The Bold, The Corrupt, And The Beautiful”; I think they would have just been better off going with a direct translation of the Chinese.

L. wanted to watch 15: The Movie, a Singaporean film from the early 2000s about teenage gangsters. The previous night we’d decided it was too long to start watching at 5:30 a.m. and still get up in time for Noisound.

I didn’t enjoy the film too much. It was stylized in a way that I felt was overdone, like a two-hour-long MTV video. It reminded me a bit Fallen Angels (Hong Kong), The Cut Runs Deep (South Korea), or All About Lily Chou Chou (Japan)—East Asian films typical of the period, all about violent young men. 15: The Movie was trying too hard to have a distinctive style; an example, maybe, of “anxiety of influence.” There was something to admire in the film’s social criticism of Singaporean society, but it also felt a bit too didactic.

I thought the acting was bad, but found out on Wikipedia that the actors in the film were real teen gangsters. Ironic. A lot of films from the early 2000s were trying for cinéma vérité in some way. I guess you don’t always end up with something like Zhang Yimou’s Not One Less or Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day, both of which used untrained actors to great effect.

I walked home after we finished watching the movie, around 1:30 a.m.. I bought instant pasta from a 7/11. I had eaten an instant burrito for breakfast/lunch from 7/11 as well. Surely, it couldn’t be healthy to eat so much 7/11 food, but I’m always in a rush and 7/11 food can be eaten on the go. I had read an article earlier that day describing Taiwan as having “an overworked, sedentary society in which most meals are eaten on the side of the road, at school or in the office”–that sounded about right. I have to admit—although I am working on cutting down—probably half of my meals are from 7/11 at this point.

In the store, I nodded a greeting to “Auntie,” an old lady who hangs around in the 7/11 night after night with her husband. I have never spoken with her. She’s usually pacing around the store, sometimes chatting with the store clerks or even helping them stock the shelves, while her husband flips through the day’s newspapers or works on the crossword. I guess they had no other family.

I remembered hearing someone compare the behavior of many elderly in Taiwan to schedule-bound NPC, or non-player characters, in RPGs. That’s the fate of a lot of elderly in Taiwan, who end up adapting these odd, repetitive schedules out of sheer loneliness. Maybe that’ll be my fate one day as well, I thought.

Brian Hioe