Joan Didion’s July 1993 essay, “Trouble in Lakewood,” is about a gang scandal at a white high school in a southern California town, the emblem of the sordid collapse of white America’s lower middle class. Twenty-five years on, there’s a temptation to see in Didion’s Lakewood early portents of the current collapse of white America’s lower middle class, still more sordid, and by now nationwide.

Didion despised the hooligans of Lakewood and their yobbo mothers in a manner recalling her contempt for the dirty, feckless hippies of her most famous essay, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” first published in the Saturday Evening Post back in 1967. I reread that one recently, too, and found myself studying her work in earnest for the first time. I’d always thought she was just some trivial, boring self-involved rich chick in sunglasses, who liked good clothes and having movie stars over to dinner. Someone for Pauline Kael to “whoop” at in 1972, and Caitlin Flanagan to swoon over in 2012. Someone for teenage girls to take too seriously.

On the face of it, “Trouble in Lakewood” is a profluent and elegant piece, drawing deep, painful connections between the postwar housing boom, the sprawling aerospace industry and the inexorable draining away of its union jobs in the wake of a huge and sudden slash in federal defense spending. With industrial decline came a creeping sub-suburban malaise that eventually overtook that whole weird little pocket of Southern California (where I grew up myself, as it happens, in nearby Long Beach.)

The result of Lakewood’s economic collapse, according to Didion, was a generation of youth with no prospects whose blind rage, pent up and convected, exploded into the shameful spectacle of the Spur Posse, a vile pack of Lakewood High troglodytes who achieved nationwide notoriety for their sexual abuse of girls as young as ten, getting in fights, dealing drugs, committing burglaries, setting off a pipe bomb on someone’s front porch, etc. (and later, angling to get paid to tell their ugly tales on ugly television shows like “NightTalk with Jane Whitney” and “Jerry Springer.”)

“Trouble in Lakewood” is about ten thousand times better than “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”—better researched and thought out, better observed and better written. The latter piece draws a frankly kind of unbelievable portrait of dumb, unwashed hippies who fed acid to their five-year-old kid and spent the whole day eight miles high, responding to most of the author’s questions with “Wow.” God knows how Didion found people quite as messed-up as these. I am a Seventies kid myself and I am here to tell you that people got high a lot back then, but I never even heard of anyone getting as wasted as Didion’s hippies do, outside of underground comix. It’s incredible that all of them didn’t just die in a big heap from all that acid and meth… okay, one of them lands in the hospital with pneumonia.

In any case both essays, written thirty years apart, are getting at roughly the same thing, namely that the American Dream is a myth and a fraud because the tough pioneer spirit that animated Didion’s own ancestors, and also John Wayne, is dead; and now these gross, unworthy new people, such as hippies and illiterate mall-shopping Lakewood matrons, deserve what they get—more or less.

Didion’s work is an unrelenting exercise in class superiority, and it will soon be as unendurable as a minstrel show. It is the calf-bound, gilt-edged bible of neoliberal meritocracy. The weirdest thing about it is that this dyed-in-the-wool conservative woman (she started her career at the National Review) somehow became the irreproachable darling of New York media and stayed that way for decades, all on the strength of a dry, self-regarding prose style and a “glamor shot” with a Corvette. The toast of Broadway and the face of Céline, decorated by Barack Obama himself, Didion is the mascot of the 20th century’s ruling class (both “liberal” and “conservative”)—that is, people who “went to a good school” and know how to ski and what kind of wine to order, and thus believe themselves entitled to be in charge of your life and mine, and just… planet Earth. Almost every college-educated person in the United States d’un certain âge (that’s the kind of phrase we liked to use) is to some degree responsible for this, insofar as we accepted it—or did, maybe, until 2016, when the failures of the “meritocracy” finally came home to roost. Or not roost, rather, so much as attack like we were Tippi Hedren.

In Didion’s reading, the shame of Lakewood is the result of a foolish belief in the pipe dream that a large, comfortable, educated working class is a sustainable or even desirable goal for American society. The tragedy of tens of thousands of people, veterans mostly, who’d come to southern California to take union jobs in aerospace and defense, people who’d bought modest houses with their modest salaries in the expectation of stability and a modest, comfortable future that did not, in the event, materialize—this was Lakewood’s own fault, for imagining that working class people were good enough to own property, good enough to consider themselves “middle class”:

“We’ve developed good citizens,” Mark Taper said in 1969. “Enthusiastic owners of property. Owners of a piece of their country—a stake in the land.” This was a sturdy but finally an unsupportable ambition, sustained for forty years by good times and the good will of the federal government.

Nowhere in this essay does Didion mention the end of the Cold War, that is, the end of an immediate imperative to produce the neverending floods of armaments and airplanes that had fueled Lakewood’s economy in the postwar period. Or, if you prefer, “good times.”

“The great events of 1991 ended the Cold War, banished the threat of global nuclear conflict, and freed us to redefine national security,” according to “After the Cold War: Living With Lower Defense Spending,” the now painful-to-read report of the Office of Technology Assessment Congressional Board of the 102d Congress. “While future U.S. defense needs are still unclear, they will surely require less money and fewer people… It is now safe to contemplate very substantial reductions in defense spending—perhaps to the lowest level in 40 years—and to turn our attention to other pressing national needs. […] from 1991 to 2001, perhaps as many as 2.5 million defense related jobs will disappear.”

Didion:

What had it cost to create and maintain an artificial ownership class? Who paid? Who benefited? What happens when that class stops being useful? What does it mean to drop back below the line? What does it cost to hang on above it, how do you behave, what do you say, what are the pitons you drive into the granite?

Bad and wrong as those questions were, the answer was staring her in face: keeping the country on a war footing paid the people who made the war machines. Who paid? We did, just as we are still, for the godforsaken neverending wars.

“An artificial ownership class.” What a phrase!—for all the world as if there were also an organic, natural or genuine “ownership class.” (If there were, you can bet your life you know who belonged in it.) But for serious now. Whence the contempt for the lost aerospace jobs of Lakewood, as if such a job didn’t even quite count as a job? Because it was a job, like any other—i.e., a series of tasks done for money—like writing an essay for the New Yorker.

An aside: I’m not trying to whitewash my own ignorance at all. In 1993 I was designing gilt photo frames and other fancy little things to be sold at insane prices at Bergdorf Goodman and Barneys Japan. I was studying Japanese for fun, saving for a holiday in Tuscany! Things were going to be great with the Republicans out of the White House!

But the Spur Posse’s in the White House now. The Spur Posse is running Congress and the Supreme Court.

Now I am about the same age Didion was when she wrote her Lakewood piece, having lived through twenty-five years of escalating disaster, the calamities of Iraq and Afghanistan, mass shootings, stolen elections and stolen Supreme Court seats, accelerating climate change, thieving bankers who never went to jail (speaking of an “artificial ownership class”), creeping authoritarianism and the abject ruination of Hope and Change, culminating last week in Michele Obama saying she loves George W. Bush, her “partner in crime,” “to death,” at which point I basically wished for the earth to swallow me whole, and had the last bit of the materialistic stuffing knocked clean out of me.

The steamy adulation of New York women writers for Joan Didion, q.v. Vogue (“the immortal intellectual and otherwise dream girl”); New York (“an eminence, almost a legend”); the New Yorker (“elegiac, magisterial”); Bustle (“the coolest writer of all time”), is particularly mystifying in view of the contempt in which Didion holds so many other women. The women of Lakewood, for example. She doesn’t like them shopping for “Heart Wafflers” on sale at Bullock’s, she doesn’t like how they call themselves “middle class,” when their husband is like a welder, or something; she doesn’t like how they’re so obsessed with high school athletics, or even how they “define themselves” as “moms.” The sneering is just palpable. This is not a lady who would dream of entrusting her Sunday brunch preparations to a department-store Heart Waffler. It’s a chilly, just barely veiled disdain, in exactly the same flavor as her contempt for the hippie girls of “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” like this teenage runaway:

I wonder what she is doing here in the Panhandle, trying to make friends with a city girl who is snubbing her, but I do not wonder long, because she is homely and awkward, and I think of her going all the way through the consolidated union high school out there where she comes from and nobody ever asking her to go into Reno on Saturday night for a drive-in movie and a beer on the riverbank, so she runs.

All this would be trivial enough, if it weren’t blindingly evident that the assumed superiority of “educated people” is a visible cause of today’s catastrophes. I’m not talking about the slamming of “coastal elites,” real or imagined, by today’s demagogues and alt-right garbagios; I’m talking about the mindset of “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” an essay that is still taught to and deeply admired by yearning undergraduate ladies who long to Write: an essay that considers the hippies of Haight-Ashbury pitiable wretches, the sign, as we were noting earlier, of a national malaise.

Right across the Bay in Berkeley just three years earlier, in 1964, twenty-two-year-old Mario Savio had spoken these words on the steps of Sproul Hall.

There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part! You can’t even passively take part! And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels…upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop! And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!

But Didion didn’t care about that, didn’t even mention the real political hopes and ambitions of young people in Northern California in the Sixties. Think about this for a second. If Top Writers like Didion had written about the legitimate concerns of Mario Savio, the Free Speech Movement or SDS, the lastingly valuable and influential aspects of Sixties youth culture, rather than getting off on themselves by talking with an allegedly tripping toddler, who knows where we might have gone, instead of where we find ourselves now.

For all their hanging out among the counterculturalists and jazz musicians and rock stars and hippies and desperately trying to be cool, I don’t think Joan Didion, or Capote, Updike, Wolfe, et al., ever wanted an egalitarian society. American writers like to pretend that their work is apolitical; it’s hard to imagine what the American equivalent of Marquez or Václav Havel might be. But no writing is apolitical. Didion and her cohort wanted a society where people like themselves could keep comfortably chronicling the interesting inferiorities of those in the classes below their own.

The depressing truth is that Didion and co. strangled the potential movement toward egalitarianism of the Sixties in its cradle. They did this with status and veiled sneers and European “sophistication” and “good taste.” They did it by posing next to a Corvette in dark glasses, by throwing a Black and White Ball, and by writing for Hollywood and in the best New York magazines for “serious money.” They did it by interpreting the hippie culture as purposeless, ill-bred, wasted and unclean—separate from and incommensurate with “educated people.” Didion and co. produced fake cultural leadership for the comfort and protection of the well-heeled and powerful. Better people, better writers, would have connected with the youth movement and the working class to protect and expand democracy—say, by putting their bodies upon the gears, and upon the wheels of the machine. Instead, they kept it running.

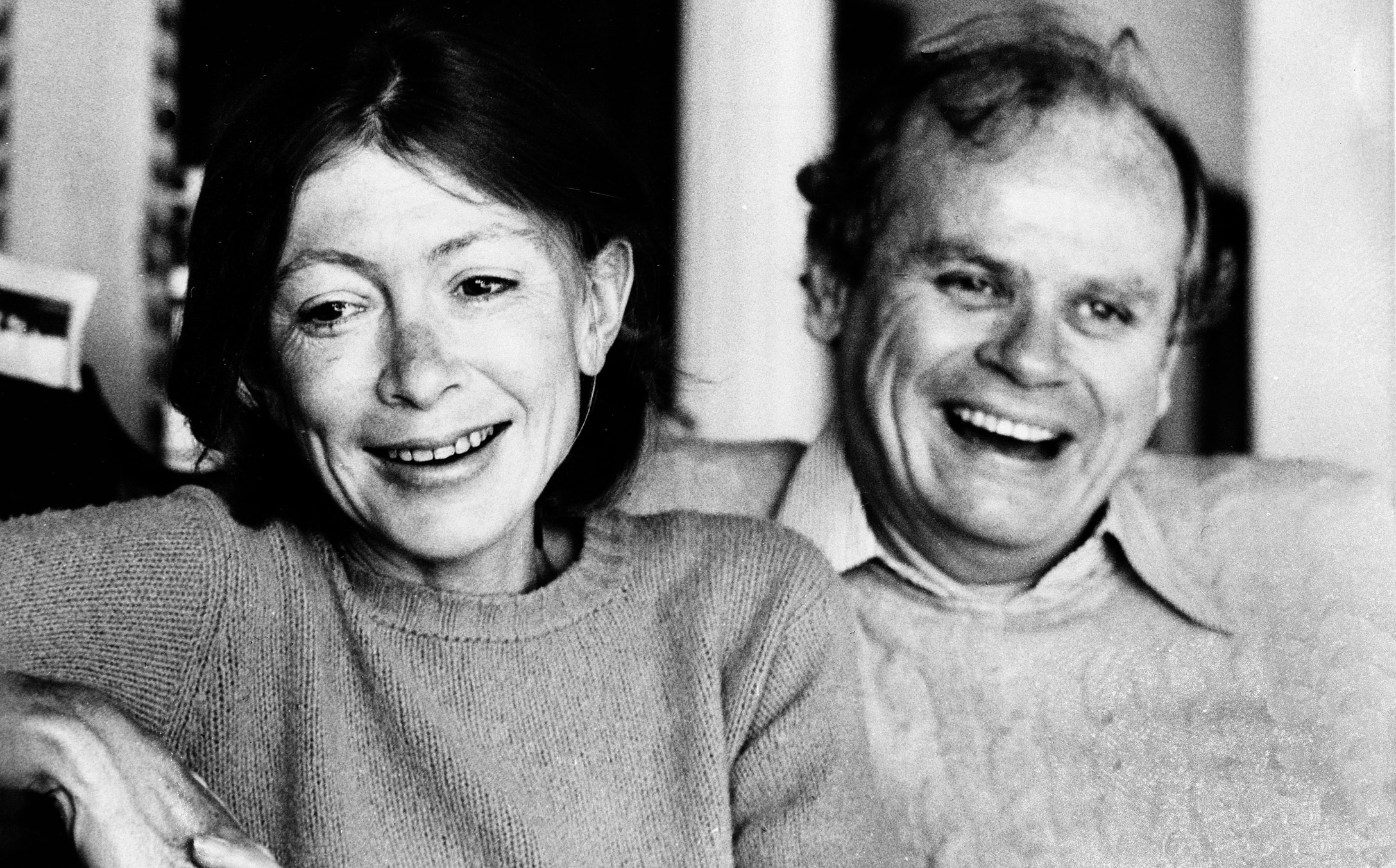

And maybe they got to where they kind of knew it. In The Year of Magical Thinking, a 2005 memoir concerning the sudden death in 2003 of her husband, John Gregory Dunne, Didion describes Dunne as having been very low in the weeks before his death. Feeling his mortality. He insisted on an impromptu trip to Paris, convinced he’d die before he could see it again unless he seized the moment.

Photo: AP

Photo: APIn New York magazine some twenty years before, an interviewer fawned over the delightful epitaph the couple had once chosen for themselves: “THEY HAD A GOOD TIME.” In 2003, Dunne was evidently revisiting this view.

We were not having any fun, he had recently begun pointing out. I would take exception (didn’t we do this, didn’t we do that) but I had also known what he meant. He meant doing things not because we were expected to do them or had always done them or should do them but because we wanted to do them. He meant wanting. He meant living.

Joan Didion, The Year of Magical Thinking

“What John meant when he said we were not having any fun” concerned Joe and Gertrude Black, whom Didion and Dunne had met in Indonesia in 1980. Joe Black had retired from the Rockefeller Foundation and come to teach political science at the Indonesian university where the two couples met. The Blacks’ faces were “open and strikingly luminous,” Didion says, and her husband had talked about them frequently over the years, “in each case as exemplary, what he thought of as the best kind of American.” Dunne mentioned them again a few days before he died, prompting Didion to search his computer for their names, which she found in a file called “AAA Random Thoughts,” where he’d written: “Joe and Gertrude Black: The concept of service.”

She knew what he meant by that, too, Didion says.

He had wanted to be Joe and Gertrude Black. So had I. We hadn’t made it. “Fritter away” was a definition in the crossword that morning. The word it defined was five letters, “waste.” Was that what we had done? Was that what he thought we had done?

The answer is yes. Just like everyone who is still ordering a steak and planning a European vacation and somehow hoping for the best in this best of all possible worlds. It’s the only thing I like in all of Didion’s writing I’ve read. The moment when the neuraesthenic-in-the-cashmere-turtleneck routine fell away.

But maybe that’s exactly what people like and will continue to like about Joan Didion. Her deranged fans are so obsessed with what she wore, to do her reporting. Her bony Céline-flogging bod on the sofa. In the recent Netflix documentary about Didion directed by her nephew, Griffin Dunne—who is crazy about her because she didn’t mock him for accidentally flashing one ball out of a too-tight bathing costume at the age of five, a tale that goes on forever—he asks her about the tripping toddler of “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.” How did she feel, as a journalist, about meeting Susan?

“Let me tell you, it was gold,” she says, after a nightmarish pause. “You live for moments like that, if you’re doing a piece. Good or bad.”

Hey. That wasn’t “gold”! If it happened, she was a monster.

But you had Rebecca Mead defending that response in the New Yorker, because it meant that Didion was the Real Thing, unflinching, a truth teller, a real journalist. Come on, man. It wasn’t “gold”!! If you see that some idiot has given acid to a five-year-old child you have to drop everything and call the police, an ambulance. As a human being, you have to do that. For the love of Betsy. Didion was supposed to be a Law and Order guy, I thought. What would John Wayne have made of that.

That’s what “wanting” is, surely? What “living” is. Just being, rather than putting on some kind of performance on behalf of I guess your biographers? The whole thing recalls that fake Gandhi remark about Western civilization (“I think it would be a good idea.”)

To put this another way, “wanting” and “living” are things that a person can very easily do in Lakewood, California. Which is a little square, okay. But El Dorado Park is really pretty, with huge old trees, and on the weekend there are a lot of families having picnics. The sea is very near by.

The author’s grateful thanks to Brian Morton.

Maria Bustillos