I was looking at the Southern District of New York’s website a few nights ago—never mind why—and was really horrified to see all the judges listed were all men. Then I realized I was looking at the judges from the late 18th Century and 19th century, before feminism fixed everything. Most of these judges seemed to be named John, even up through the nineteenth century. But one name jumped out at me, and it was Learned Hand, who was a judge in this office from 1909 to 1924. Jesus Christ! Learned Hand! What an intense guy he must have been, walking the streets of lower Manhattan over a hundred years ago, a judge named Learned Hand, his craggy face taking shape under the gas lamps as he emerged from the brown mist.

I expected to have to dig for information about him, but in little time I discovered that Learned Hand could have worn an “I’m kind of a big deal” T-shirt with zero shame. Learned Hand is/was, I am embarrassed to report, very very famous. If you already knew this, you’re saying to yourself, yeah, “Learned Hand, you idiot,” but if you have never heard of him, if you are not a lawyer, that is, or just an usually erudite person, probably over 50, you’re still where I was when I very first saw his name, which is to say, lost in a world of “Learned Hand, was that a real person, is this a joke, did a person with a really dumb sense of humor hack the SDNY website, can you imagine how craggy this guy’s face was.”

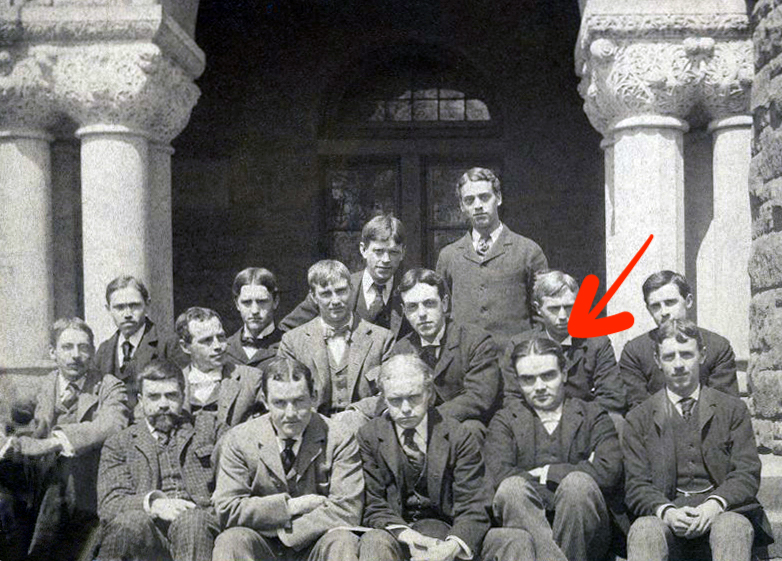

Learned Hand was born in 1872 in Albany, and grew up there. Imagine him as a boy, sitting in some stone-turreted mansion on State Street, reading the Book of Common Prayer to his mother as she clutched a handkerchief to her mouth. His real first name was Billings, and everyone called him B (This is some extremely preppy shit). He attended Albany Boys Academy, and is indeed a featured alumnus on the school’s Wikipedia page, chosen over Herman Melville, Andy Rooney, and a frankly not very nice boy I went on two dates with in 1986.

After Harvard and Harvard Law, Hand practiced law in Albany and lived with his mother. He never went out with any ladies, then he met someone and just married her very fast, and later in life she had a very long affair that he seemed resigned to. (Hmmmm.) He was briefly interested in politics, then he worked for the SDNY, then, in 1924, he was appointed by Calvin Coolidge to serve on the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, where he remained until his retirement in 1951. He died in 1961.

Learned Hand, lawyer friends told me, was famous because he was pithy, and a good writer. Here are some examples of Learned Hand’s pithy-ness, and my sense of the man—the most quoted judge in American history who didn’t make it onto the Supreme Court, an odd way to be described, but how he is described nonetheless—and my comments.

[Woodrow Wilson] is the type of statesman which I most distrust, and individually a most repellant human being, on the whole the American president for whom I have achieved the greatest personal dislike.”

Woodrow Wilson was definitely bad. Yes, Learned Hand, I agree.

You may ask what then will become of the fundamental principles of equity and fair play which our constitutions enshrine; and whether I seriously believe that unsupported they will serve merely as counsels of moderation. I do not think that anyone can say what will be left of those principles; I do not know whether they will serve only as counsels; but this much I think I do know — that a society so riven that the spirit of moderation is gone, no court can save; that a society where that spirit flourishes, no court need save; that in a society which evades its responsibility by thrusting upon the courts the nurture of that spirit, that spirit in the end will perish. What is the spirit of moderation? It is the temper which does not press a partisan advantage to its bitter end, which can understand and will respect the other side, which feels a unity between all citizens—real and not the factitious product of propaganda—which recognizes their common fate and their common aspirations—in a word, which has faith in the sacredness of the individual.

I’m not going to argue with someone who was born in 1872 about how fucked up and privileged the idea of moderation is. Out of kindness to myself and to the memory of a man who, unlike people alive today, had an excuse maybe to think dumb stuff like that, I will instead focus on the the other main point here, which seems to be that if a culture is going a certain way and its citizens are largely possessed by either very bad or very good ideas, there’s not a law that will change the tide. I think I’m with Mr. Hand on this one, especially when it comes to all the people who think that mythical “American ideals” will somehow rescue us from our present situation, which was caused by actual American ideals.

There is no surer way to misread any document than to read it literally. … As nearly as we can, we must put ourselves in the place of those who uttered the words, and try to divine how they would have dealt with the unforeseen situation; and, although their words are by far the most decisive evidence of what they would have done, they are by no means final.

I like to believe that Learned Hand felt so strongly about this that he would not have just been BFF-opera-buddies with Antonin Scalia, even though their shared interests include being dead.

The day has clearly gone forever of societies small enough for their members to have personal acquaintance with one another, and to find their station through the appraisal of those who have first hand knowledge of them. Publicity is an evil substitute and the art of publicity is a black art; but it has come to stay, every year adds to its potency and to the finality of its judgments. The hand that rules the press, the radio, the screen and the far-spread magazine, rules the country whether we like it or not, we must learn to accept it.

I am happy for Learned Hand that he died well before the birth of Jonathan Cheban, a Kim Kardashian BFF otherwise known as The Food God.

In each case [courts] must ask whether the gravity of the “evil”, discounted by its improbability, justifies such invasion of free speech as necessary to avoid the danger.

Hand might be best known for this last one, his tweak, if you will, of his more famous colleague Oliver Wendell Holmes’ more famous legal standard, from 1919’s Schenck v. United States, known as “Clear and Present Danger.” This phrase is just as it sounds—when it comes to threats against the government, the threat must be immediate and obvious for the courts to intervene. Now, Hand had throughout his career been seen as sort of advocate for the First Amendment and free speech: in Masses Publishing v. Patten (1917) Hand ruled that a postman’s refusal to distribute a mailing attacking capitalism violated the First Amendment and in 1934, he ruled that James Joyce’s Ulysses was not obscene.

But once the red scare was in full swing, in the 1950s, Hand became more nervous about Communists and Communism than he had been thirty years before. Though most communists were not inciting immediate violence against the government, and hence not meeting Holmes’ standard, Hand wanted to come up with a way to establish them as being in violation of the law. The last of the the quotes above, from the trial that became the 1951 Supreme Court case Dennis v. United States, reflects that reasoning: if whatever was at risk of happening—the United States being taken over by Communists—was truly and incredibly terrifying, then it didn’t really matter that the Communists were not, at that moment, about to do anything really awful. The problem was that they were reading Marx. The emphasis, in Hand’s analysis, was not on what they might do, but on what they wanted to do, even hypothetically.

The Supreme Court decision adopted his standard, making a point to bestow praise upon Chief Judge Hands’ prose: “We adopt this statement of the rule. As articulated by Chief Judge Hand, it is as succinct and inclusive as any other we might devise at this time. It takes into consideration those factors which we deem relevant, and relates their significances. More we cannot expect from words.”

The results were not good. After Dennis, 145 American Communists were arrested and prosecuted, in one of the agreed upon most embarrassing moments in our history. It was not until 1957’s Yates v. United States that everyone decided again that there would have to be an actual threat to establish danger.

In conclusion, it seems that it is entirely arbitrary whether or not a court wants to decide if something is a threat to the government or not, and this seems bad, and even though Learned Hand was Good at Writing, he was probably not good at helping people be more free, which is not terribly surprising, since he was a judge. In the end, I am sad to tell you that after an entire lifetime of having no idea who Learned Hand was, the only thing I can promise to remember about him is that his grandson, Richard, went out with Marcia Cross, the actress who played Bree Van de Kamp in Desperate Housewives, and Kimberly Shaw on Melrose Place, and that he was much, much older than she was.

Sarah Miller