My generation in Taiwan grew up surrounded by parents and relatives who swear by fortune telling, and a number of friends my age are into it. Those who believe in fortune telling appear to believe that a “good” fortune teller is someone who tells them what they want to hear, while a “bad” one does the opposite. But either way, some of my friends give an astonishing amount of weight to their fortunes. One has stayed at a job she’s hated for over a year, evidently because fortune tellers keep insisting that with the poor economy, it will be hard for her to find another job. Another went obsessively to have his fortune told while struggling desperately with an unrequited love. In the end, as I recall, it did not work out for him.

There is still a great deal of traditional belief in ghosts and spirits around as well, and young people may or may not believe in their existence—so long as there’s no harm, many seem to think, they might as well believe.

You have many different kinds of fortune telling in Taiwan, with techniques including face reading, palm reading, calculating fortunes based on one’s birthday, or even using birds.

At temples, one may shake a cup with a number of lottery sticks in it and choose a stick that falls out. You then throw a set of wooden “moon blocks—known as jiaobei (筊杯) in Mandarin but in Taiwan, almost exclusively referred to by the Taiwanese pronunciation, bwa bwei—onto the ground, in order to determine whether this is the right stick. When the moon blocks land the right way, to indicate that this is, in fact, the right stick, you can withdraw a paper fortune from the corresponding drawer in order to learn your future.

Or you may consult a spiritual medium. My favorite of these methods involves Ji Gong, the drunken monk deity. Spiritual mediums invoke him by, as you might guess, drinking large quantities of alcohol, usually kaoliang.

The ability to see the future sounds like it could be a useful side-effect of drinking. though generally, being a spiritual medium is considered a high-risk job. The high cost of fortune telling is seen to some degree as a recompense to mediums for the burden they bear of seeing the future. The burden of prophecy.

Having spent my formative years outside Taiwan, these practices were never integrated into my everyday life. But the longer I live in Taiwan, the more I find myself developing a sort of casual, half-serious belief in traditional spiritual practices. I still avoid having my fortune told, though, since I know that whether I believe in it or not, after having my fortune told, I won’t be able to stop thinking about whether it could be true or not. I would never be able to stop thinking about it!

For this reason, I try not to think too much about the future, or fate, or causality, or any of those things. Either you find yourself believing in absolute fate, in which everything is predetermined, or else that the future is simply meaningless, indeterminate chaos.

I don’t like either option, frankly. However, I’ve long since realized that I tend to be paranoid, and think too much about the patterns one randomly encounters in the world.

When I was a kid—probably struggling to some degree with OCD—apart from the compulsion to wash my hands obsessively, sometimes until they bled, I had also a paranoid fixation on washing my hands an even number of times per day; otherwise, I was sure, I would meet with some kind of terrible calamity. Whenever I had a bad day in elementary or middle school, I had the strong tendency to attribute it to my having disturbed the cosmic order through washing my hands the wrong number of times.

Now, as a messy and disorganized adult, I sometimes wonder where all my childhood fixation on order and cleanliness went. Some level of that sure would be useful now. It’s strange to think that, as a child, I was terrified of eternal damnation simply on the basis of having failed to wash my hands the right number of times. I was one weird kid—that’s for sure—but also, what a terrible and senseless universe it would be, in which one could face cosmic doom for… hand-washing.

When I have a bad day now, rather than attribute this to washing my hands the wrong number of times, I remind myself that there is, in general, no logical or causal connection between the various things that made my day bad. After all, having a pitch rejected or having to deal with a fussy translation client has no connection to, say, being stuck in a traffic jam or having an unexpectedly long wait at the MRT that made me late to something. Once I can disconnect the imaginary links between these things, logically smoothing out in my head that they are not related, I feel better.

Interpreting patterns out of random chaos is how we make logical sense of a messy world, but our capacities for pattern-recognition sometimes go a bit overboard, and we create the patterns instead of just interpreting them. That may be how superstition originates. But it’s natural, I think, to come up with little rituals to get through the day, as a way to make sense of the chaos of quotidian existence. That is, we develop our own coping rituals.

Brian Hioe

Brian Hioe Brian Hioe

Brian HioeSince I pass nightly through a night market offering a kaleidoscopic array of T-shirts bearing strange English slogans, I’ve recently taken to trying and predict the future on the basis of the shirts I see.

Brian Hioe

Brian Hioe Brian Hioe

Brian Hioe Brian Hioe

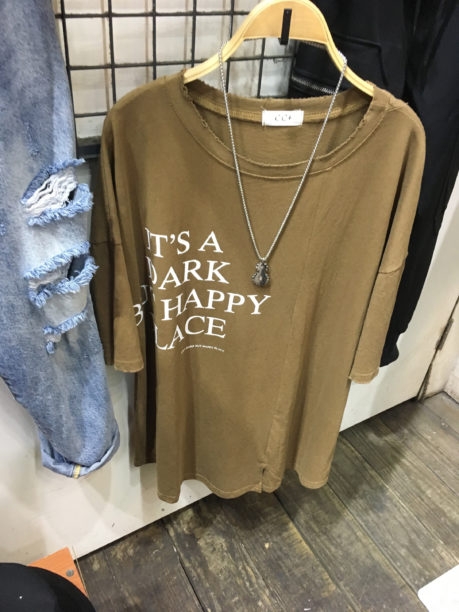

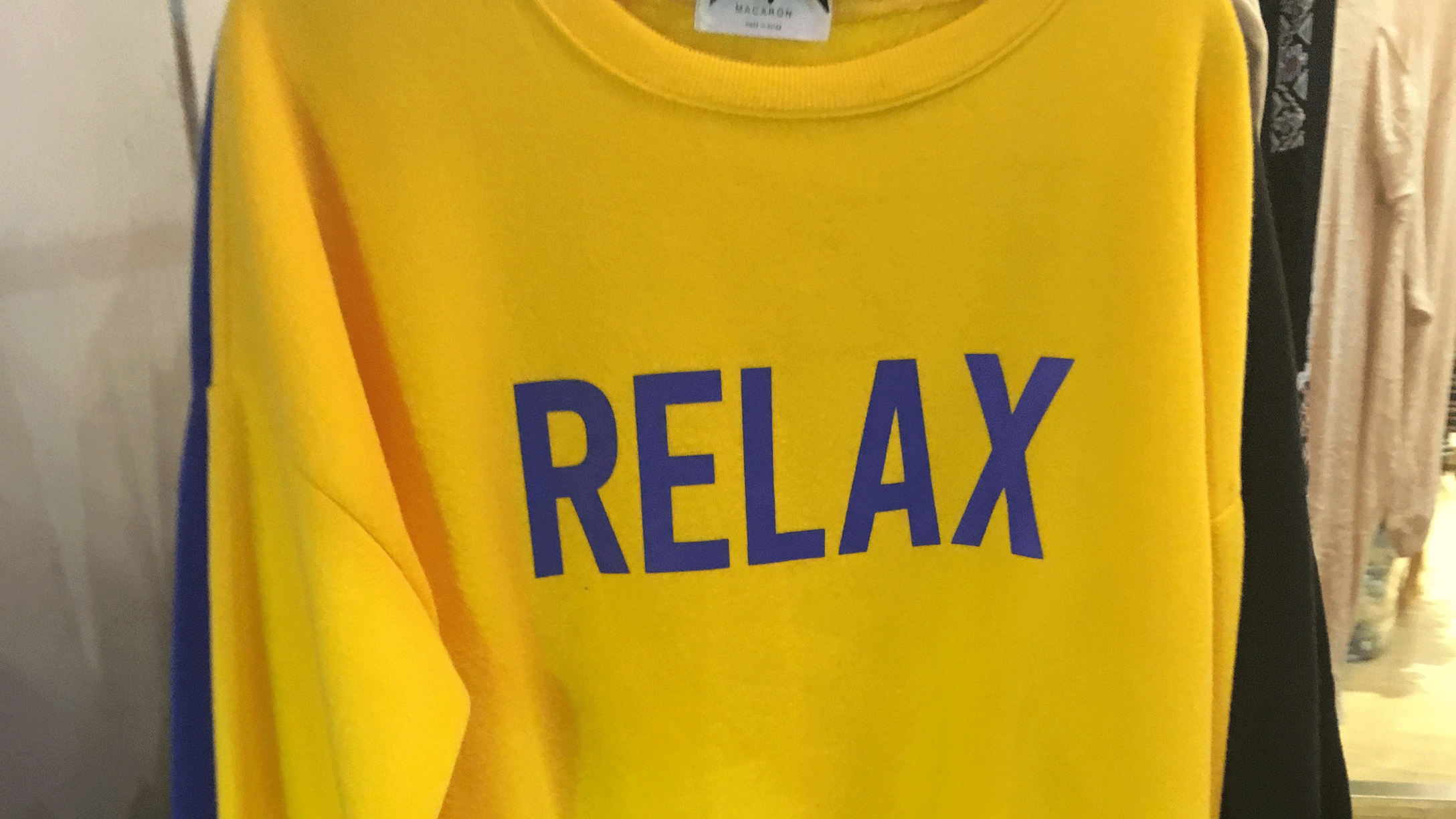

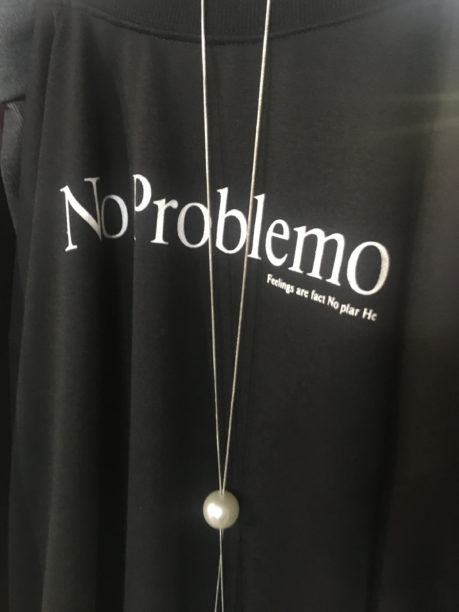

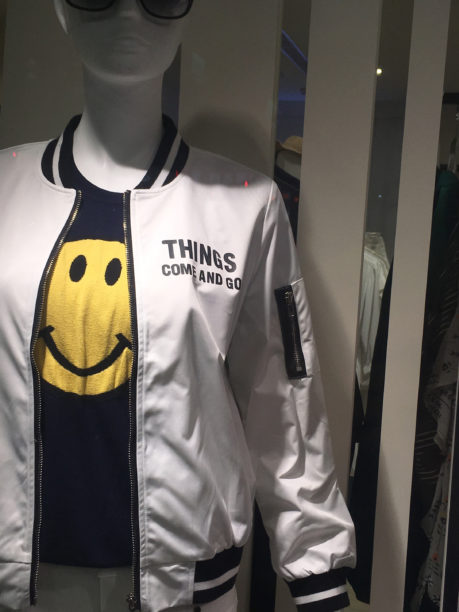

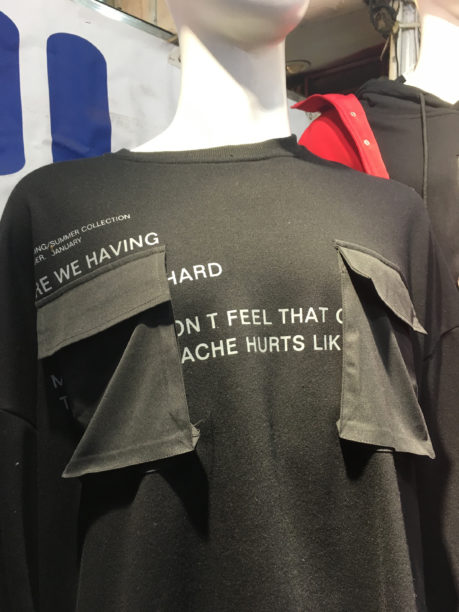

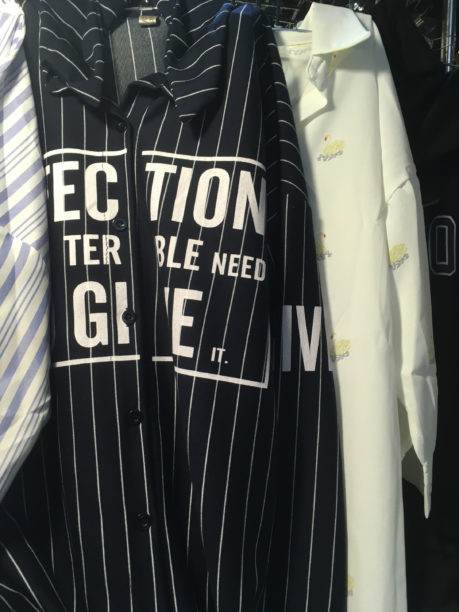

Brian HioeAnd I can’t help feeling as though the cosmos is calling out to me sometimes, attempting to communicate with me through night market t-shirts. Too often, when I’ve been having a bad day, I’ve come across a night market shirt that seems to be giving me some form of advice, like “RELAX,” “No Problemo Feeling are fact No plar He”, and “THINGS COME AND GO”. Or “ARE WE HAVING HARD ON T FEEL THAT ACHE HURTS LIK”, “FECTION TER IBLE NEED GIVE IT”, or “IN MY NAME HIS HORNS WILL BE EXALTED…DON’T IRRITATED.”

Brian Hioe

Brian Hioe Brian Hioe

Brian Hioe Brian Hioe

Brian HioeHeading back from a friend’s birthday party one night, I found myself thinking that I should stop thinking of myself as someone in their mid-twenties, but admit that I am in my late twenties now, I came across a shirt that said, “Youth: Good things come to those who wait.” It really is hard to shake the idea that some higher entity is trying to communicate with me sometimes through night market t-shirts. With anti-gentrification protests being a topic I have been covering in the past month, I recently came across a shirt that said, “Run your city,” something I interpreted as meaning, “Take back the city.” Another quite literally read, “BE REASONABLE DEMAND THE IMPOSSIBLE,” I guess some version of the Debord slogan. Indeed, feeling rather misanthropic about the rise of conservative forces in society, I also recently encountered a shirt that read “WE BLAME SOCIETY BUT WE ARE SOCIETY.” And as for life, which quite often seems like it’s nasty, brutish, and short? According to a night market shirt, “It’s a dark but happy place.”