In Taiwan so far there have been no nationwide lockdowns, life continues as normal, and as of writing, there are only around two hundred cases in the island as a whole. This may be due to the quick response of the Taiwanese government,with interventions by the state into private industry. Taiwan also has universal healthcare, and a functioning government.

Still, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has quadrupled in Taiwan in the last week. That’s life. Sometimes you’ll be watching a disaster unfold from afar and then suddenly it’s upon you.

A friend, a Chinese student currently doing a Ph.D. in Taiwan, hasn’t left home at all for over a month. She’s from Wenzhou, one of the most heavily affected areas in China. She’s been attending class through video-conferencing software.

After it started getting bad, I tried contacting an ex from Hubei—the province where the virus originated—whom I hadn’t spoken to in a while, but no response on email or text. I’m no longer on WeChat because of security concerns, so I couldn’t get in contact. But I managed eventually to make contact through a mutual friend—they were alright and in Beijing. That was a relief.

Most days, I try to avoid non-essential activities and just stay in my apartment. If I do go out, it’s usually for some kind of work meeting. Since I’m usually most active at night, that proves a natural form of social distancing. It’s a strange feeling, only ever encountering the other people out and about at the late night, and never really leaving Bangka.

These days, it feels like I’m watching the world burn from afar. I usually am sitting in front of my computer working through two news cycles, the Taiwanese news cycle during the day, then the US news cycle into the late night. Every day, there seems to be some kind of new cataclysm on the horizon. Just there hasn’t been any significant disruption to my own life yet.

Taiwan’s borders were shut to foreigners the other day, which means that people whose visas are about to expire may have to return to their home countries, even if these are countries heavily affected by the coronavirus and even if traveling at a time like this seems like a pretty good way to cause the coronavirus to spread further.

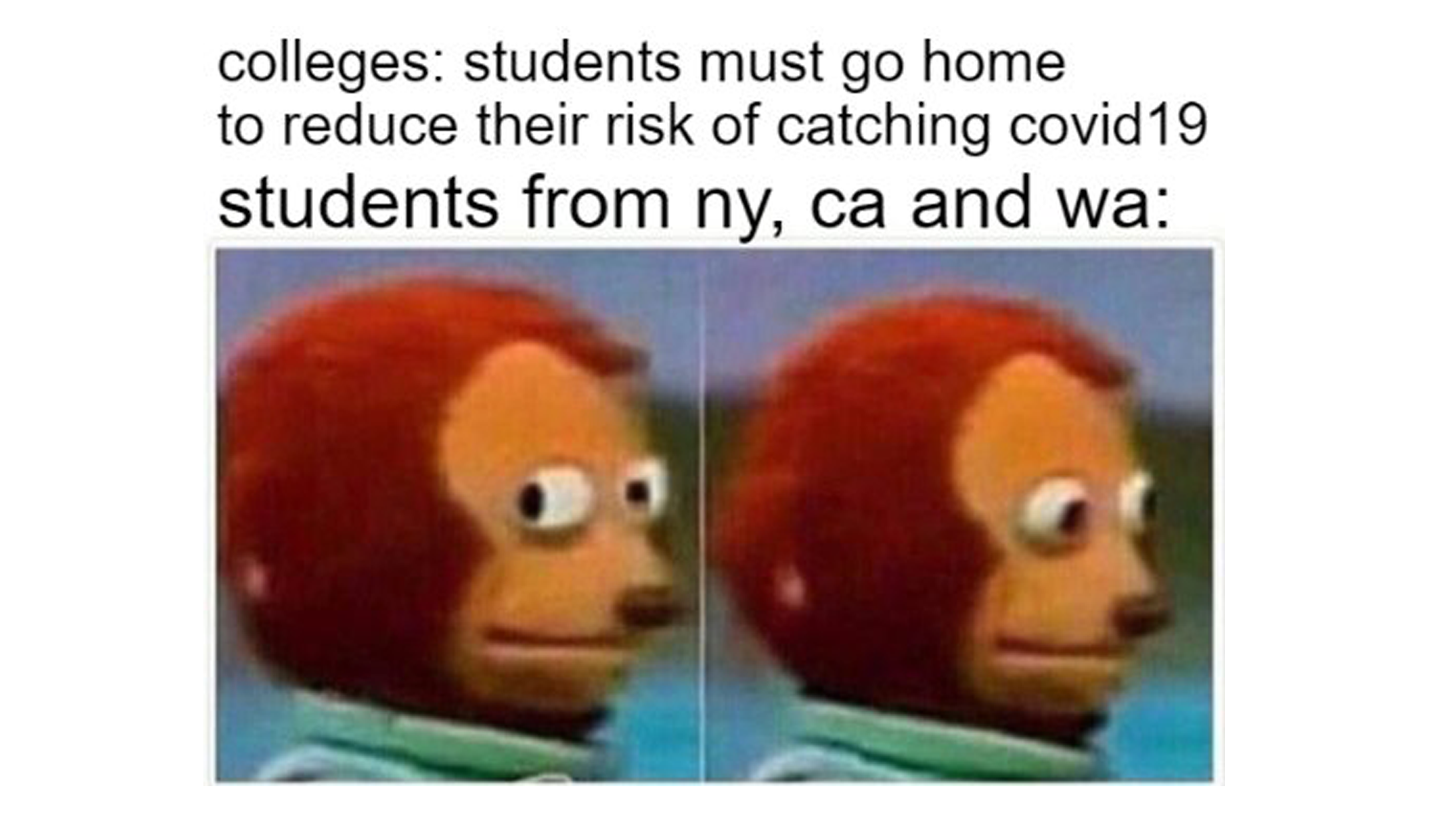

Two interns at the magazine I run, both of them American, had to go back after their programs were canceled, even though it’s safer right now in Taiwan than in the US. It seems that colleges are afraid of liability if students were to contract the coronavirus outside of America. International students have been a particularly vulnerable population. This fits that pattern.An extension was later rolled out, but generally, I don’t know what will happen to a lot of my non-Taiwanese friends; I fear they may have to end up having to go back to danger zones.

Recently I got drinks with a friend who had just gotten back from Hong Kong. Since we hadn’t seen each other in a few months, we drank until 5 AM in a park. The police even came because we were too loud, though we got off with just a warning.

The next day, he texted me, “I’m in Taichung now. I just woke up.” It was 7 PM. He had managed to get back to his apartment in another city after that all-night binge, somehow.

Two days later, he texted me again. “I’m in Okinawa now.” What????! Apparently, his partner, who was from Hong Kong, had been planning to come to Taiwan to get out of the situation there. They were planning on going into quarantine together. Love in the time of the coronavirus, I guess. But after a sudden shift in border policy, all arrivals from Hong Kong were blocked from entering Taiwan. They decided to divert to Okinawa instead. They’ve been there for close to two months now. These are the times we live in, I guess.

The coronavirus exposes the ways in which this world is deeply interconnected—something few really understood, to the detriment of… basically, well, everybody.

The governments of the United States and the United Kingdom, for example, seem to be run by psychopathic and incompetent right-wing buffoons, as a result of which there was a failure to grasp that the coronavirus wouldn’t just stay “over there” in Asia. Informed and intelligent experts were aghast, but to no avail. This failure to grasp that the coronavirus threat wasn’t just a threat that would only affect Others in far away Asia will ultimately affect everyone. The failure of government in the United States or the United Kingdom to take proactive steps to fight the disease ultimately affects the whole world, even places that were already affected and recovering. Just as how, if the Chinese government had acted sooner in heeding the warnings of whistleblowers instead of trying to forcibly silence them, the overall number of coronavirus cases would be much lower today. The mistakes each government made in failing to take preventative measures ultimately has a cumulative effect on humanity writ large. It adds up; the effect is exponential.

Governments everywhere have placed greater priority on preserving their own power and political legitimacy than on fighting the disease. Again, the Chinese government initially tried to punish those who sounded the alarm about the disease outbreak. Only public outrage finally forced the government to respond. The Trump administration was slow to begin testing for the virus, evidently because it hoped to keep infection numbers low for the sake of elections.

The Japanese government is reluctant to call off the 2020 Tokyo Olympics , despite the danger, downplaying the threat of the virus and attempting to carry on as if everything is normal; only over the weekend did reports emerge indicating that Japanese politicians were considering a delay. For fear of social and economic disruption, a number of countries in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East initially claimed to have no cases of the coronavirus even though that’s statistically impossible. For example, many of Taiwan’s coronavirus cases are from travelers that visited Turkey–a country that until recently claimed to have no coronavirus cases.

Governments have even taken to using the coronavirus in order to further their geopolitical aims. Given its successes in fighting back the disease, the Chinese government is attempting to shift blame to its geopolitical rival, the United States, including engaging in conspiratorial claims that the CIA is responsible for the disease. American politicians, on the other hand, are threatening to take measures against China for failing to fight the pandemic earlier and in this way, negatively affecting global health–though America has more or less done the same.

And governments–particularly authoritarian ones–have used this as an opportunity to expand state power. This has been particularly visible with surveillance states, such as China and Russia. When the crisis passes–if it does, state surveillance seems likely to remain at an expanded level.

As observed in deportations of immigrants back to their home countries, despite that this could cause the disease to spread further, the priorities of the state are on enforcing the borders of the nation-state above all else. One notes that the coronavirus spread further in China because healthcare is tied to whether one has an urban or rural household registration, forcing individuals to travel to seek medical aid. Something similar is likely to occur on a global scale now.

But at the same time, a lot of what people were previously told was impossible by the government or by politicians is suddenly possible. You have state intervention in the private sector from people for whom this was previously anathema, promises of cash handouts and the like. Injections of trillions of dollars of stimulus packages, enough to wipe out all student debt in the United States and more. There’s a cruel irony to that.

The other day, nine cases were reported in the town in New York next to the town where I grew up, and where my parents still live. I guess that marked the entrance of the coronavirus into the American side of my lived experience. Before that day, the second-largest daily jump in reported cases in Taiwan had been ten cases, yet there had been a jump of close to the same number in just one day in a single town in New York. By now, New York accounts for 5% of all cases in the world.

Daniel Case/WikiCommons/CC

Daniel Case/WikiCommons/CCThe new cases in New York were in a town called Kiryas Joel, which is mostly populated by ultra-Orthodox Satmar Hasidic Jews. By the numbers, it was the poorest place in America in 2011, though poverty in the traditional sense is nonexistent in their tight-knit religious community.

After those cases were reported, a local doctor warned in a video that went viral that Kiryas Joel might have 90% infection, due to the large population in a small area there, though he didn’t provide any explanation of how he had arrived at this number. The claim was then reported on by local media, leading authorities to begin looking into the matter. Local authorities debunked the video, but by that time the county executive had already called on the state government to declare Kiryas Joel a quarantine zone.

Concern that Kiryas Joel might be a place where COVID-19 could rapidly spread was understandable. The rapid spread of COVID-19 through religious communities that have persisted in congregating in numbers, sometimes in defiance of authorities, was already clear. This was how COVID-19 went out of control in South Korea, for example, due to mass infections among the Shincheonji Church of Jesus, with one woman who was part of the church having over 1,100 traced contacts. Schools in Kiryas Joel initially did not close, despite orders from the county commissioner.

Still, a lot of the concern seemed to just come from fear of the Other. Comments in news articles about the situation in Kiryas Joel were often anti-Semitic, with calls to blockade the town and leave those there to die. This too is understandable, gven longstanding tensions between the Hasidic community and residents of surrounding communities. The residents of Kiryas Joel vote as a bloc, and they have been accused of voting strategically in order to gut the governments and school systems of other communities; some view them as actively hostile toward their non-Hasidic neighbors. The community has also been characterized as a theocracy with no separation of church and state, in which there have been attacks on religious dissidents.

In any case, anti-Semitism has been a recurring issue in the area, which tends to consistently vote Republican. Last time I was there, it was all Thin Blue Lines, Blue Lives Matter, and Support Our Troops everywhere. It all seemed quite familiar. Again, I was reminded of calls to blockade China entirely after the disease outbreak, that China and Wuhan should be “punished” for being where the disease outbreak started, or at least punished for mismanaging the pandemic.

I was reminded of the wave of violence against East Asians across the world because of the association of the COVID-19 coronavirus with East Asia. Just here, it was transposed to a different set of actors, with Hasidic Jews blamed instead of people of East Asian or Chinese descent. Once more, the same kind of behavior everywhere in the world. People sure do love their boundaries.

I sent an article about the situation to a high school friend. “These comments,” he said, after scrolling down, “Wow.”

I responded that I wasn’t too surprised.

“We are terrible people, haven’t you figured it out?” he joked. He was probably referring to people from our town. Or maybe Americans more generally.

“Aren’t we all?” I said. “Humanity.”

The coronavirus is spreading unnecessarily because of individuals or groups who don’t self-report or who defy quarantine measures, seemingly believing that the rules don’t apply to them. You can scale this up to the level of nation-states, with governments slow to react to the spread of the virus because they just don’t seem to grasp that what’s happening in other countries will happen to them, too.

This has all gotten me to thinking that whether we—as humans—live or die, it will be as a species; humanity is in a sense a single organism. The question is whether we come to understand our interconnectedness before we destroy ourselves. And sometimes I really question whether we will. What I’ve seen in past months is that we’re very good at drawing up borders and justifying exceptions, if nothing else.