In March 1977 the iconic National Geographic cover of Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun (King Tut) appeared on my parents’ coffee table. For months, I did little else but stare at King Tut’s beautiful gold-and-cobalt death mask. Underneath the photo, the copy for the accompanying story about Egypt itself—“HER DAZZLING PAST / AND HER HOPEFUL FUTURE”—was, and still is, the best poem I’ve ever read, though I would have removed the “and.”

I begged my parents to take me to the massively publicized King Tut exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was just three hours south of our home. They said no. I remember one conversation in particular, driving with my dad one day when he told me that it would be “too expensive” to go see King Tut. This is enraging to think of as an adult, because we were probably on our way to buy an antique bookcase, or a boat.

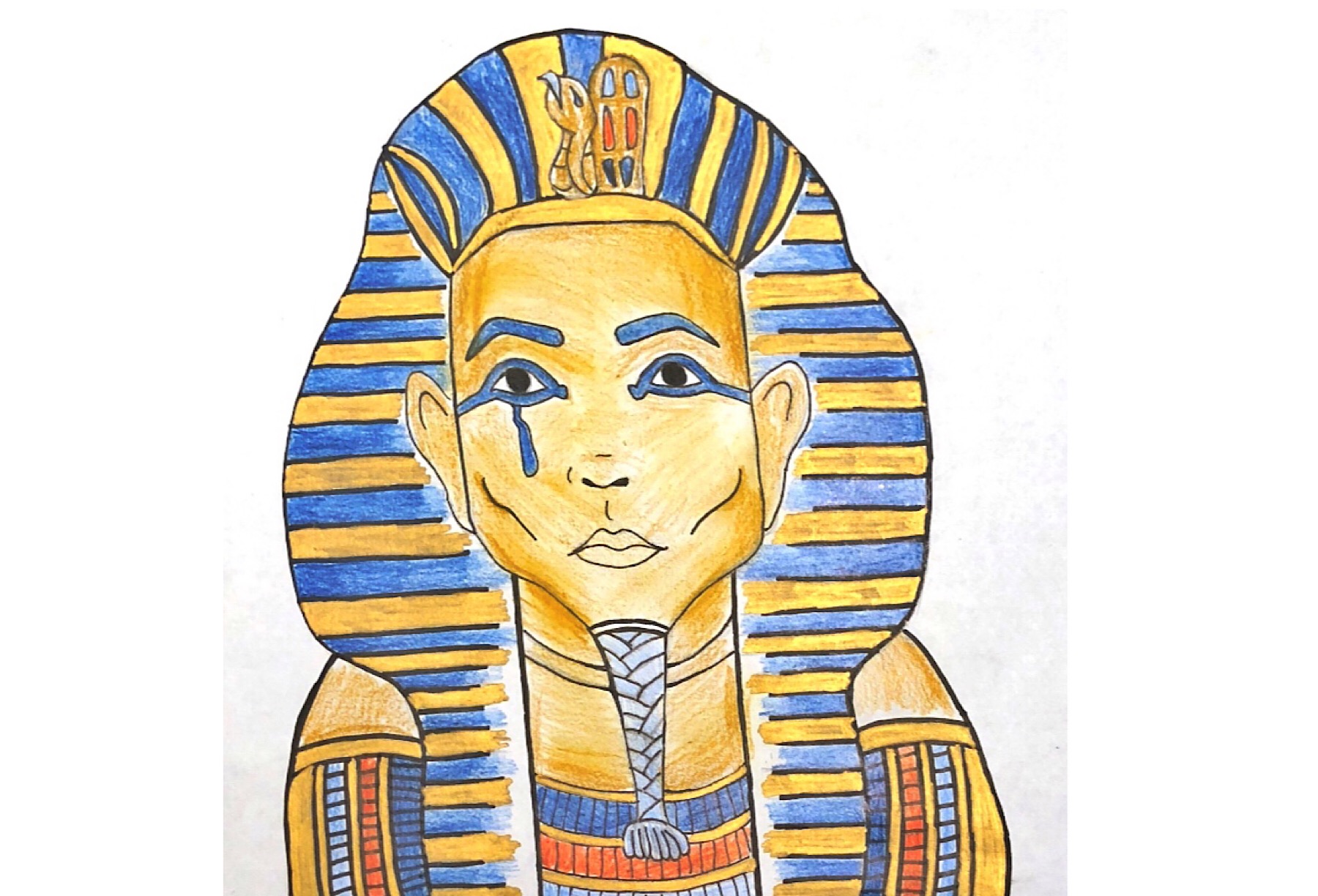

How it might have comforted me then to know that 3,000 miles away, around this time, my future best friend Heather had also seen the cover, and was enamored of all things Tut. One afternoon, at Louise Van Meter Elementary in Los Gatos, CA, the teacher announced to Heather’s class that the King Tut exhibit was coming to San Francisco. After school, Heather ran all the way home and breathlessly informed her mother of this amazing news. Six months later Heather’s mother got two tickets to the show. She took Roberta, the next-door neighbor. Heather threw all her grief from being left at home into a colored-pencil illustrated rendering of Tut’s famous death mask, for which she won third prize in a competition at the 1980 Santa Clara County Fair. A re-creation of this very drawing is posted above.

When I arrived in Los Angeles last Friday night, some 40 years after our respective Tut heartbreaks, Heather told me that a new, different King Tut show had opened in Los Angeles. How was it different? We didn’t know, we never found out, it was different the way one band tour is different from another. Tickets were somewhere around 10 billion dollars, but we decided to go anyway, Heather, me, and her girlfriend Molly. Were we wasted when we made the decision? It’s possible. It’s possible that if you too had only wanted one thing in your life and your parents had cruelly prevented you from having it, you would have been wasted too. That’s not the point. The point is that we had to get up early enough in the morning before the show—our tickets were for 11 a.m.—to get the right weed for it.

The dispensary helpers were young and beautiful and largely unhelpful. “Stoners shouldn’t be allowed to sell pot,” Heather said. “It should be sold by scientists.” I said I wanted the lowest-dose thing they had and they gave us some red gummy rings. I ate a piece the size of a pencil eraser, and within five minutes everything went extremely bright and was way more interesting than I wanted it to be. That said, I guess this was the feeling I had been seeking: I tend towards being unable to absorb things like Tut. I sprint through museums, “Red painting, green painting, painting of person, painting of cat, pardon me, is there by any chance a gin exhibit?” I saw Mayan ruins last year in Guatemala and I kept trying to fascinate myself. “REAL PEOPLE USED TO WALK THESE VERY PATHS THOUSANDS OF YEARS AGO.” But I was just obsessed with everyone’s hair, and how this Spanish lady on my tour was insane, but also, trying to make her give me candy.

On the drive to the California Science Center, down near USC, I was just blown away by the landscape of Los Angeles, the dry palm tree fronds holding up the healthy green ones, the ugly apartments next to the fancy houses, the clothing blown against the guardrails on the freeway. “I love Los Angeles too much. It hurts how much I love it. Look at the blue sky behind the white skyscrapers! I could just die right now! Molly, were you obsessed with King Tut when you were little?”

“Please,” she said. “I’m from Buffalo. We wouldn’t even allow ourselves to dream of such things.”

I had never been to the LA Science Center before. It sort of felt like a museum and it sort of felt like a mall. There was something called the ExploraStore and I kept trying not to look at it. “That store is hideous,” I said. “Not at all befitting a man of Mr. Tut’s stature.”

“What I heard,” Heather said, “is that the exhibit organizers were like, ‘Mr. Tut, you can have all green M&Ms but the ExploraStore is really central to the Tut brand mission, and, FYI we are going to sell tone-on-tone T-shirts with your initials, KT.’ Anyway, Tut was like, ‘Just put it in the contract.’ ”

Written on the wall outside the entrance to the exhibit was a quote from some archaeologist about how holding Tut’s glove (the world’s oldest) was the most profound experience he’d ever had as a human being, bar none. There are things you dream about seeing when you’re stoned. For me, this quote was beyond those dreams. I read it a hundred times, and tried to make Heather and Molly read it, but I couldn’t get a lot of traction. Today, I called the California Science Center to get the exact wording and was told no such quote exists.

I went to the ladies’ room. Two seven-year-old girls were washing their hands at the sink and wanted to tell them how lucky they were that their parents were like, “Oh sure of course we will take you to see King Tut because that’s what parents who have disposable incomes do for their children when they’re normal and care about you,” but I managed to restrain myself.

The King Tut exhibit began on time and was divided into two parts. There was no leader, or maybe there was and I didn’t notice them, but somehow we were sort of ushered from one part to another in an organized fashion. Each of the two parts began with a movie that we watched with our group in a black-curtained room, standing up. I would love to tell you what the movies were about but I don’t remember, and I took notes but I can’t read any of them on account of the darkness and being super high. I am pretty sure the first movie was about Tut himself. He became king when he was 10, he died when he was 19. For some reason I had forgotten this and it made me a little sad that King Tut had not done anything, other than be rich and also possibly hot, to deserve this attention.

After the movie the sort of earnest, museumy, antiquities-in-glass-cases portion of things began. These antiquities, in this case, were the things they put in the tomb so King Tut would have a funner time being dead. The rooms were dark and cool and glowed a pleasant Tut blue. The music was like if King Tut and Enya had a baby that whispered its own name, Tutankhamun (minus the junior), over and over. We clustered dutifully around some urns. There was one white ivory extremely fancy urn that was clearly the best urn and I wondered why the curator wanted to be so mean to the regular urns. There was lots of jewelry like you’d see women in Sedona wearing, but obviously better.

Museum text explained what everything was, this is a necklace (got it) this is a pectoral (some sort of decorative chest plate, OK, from the Latin above the pecker) this is a cartouche. What was a cartouche? It seemed like anything could be a cartouche.

The gold funerary bed was there, and I remembered it as a famous thing. It was clearly designed for analysis in the underworld, and I guess the people that gave it to Tut did not realize the extent to which Tut’s problems were seriously OVER, unless of course “I just don’t know what to do with all of these cartouches, and by the way, what are they” is a conversation post-alive Tut felt he needed to have with a disinterested professional.

The second part of the exhibition also started with a movie, also, sorry, I don’t remember what exactly it was about. If I were forced to guess I would say it had to do with this English dude, Howard Carter, and how no one believed in him when he said he could find Tut, but then he did, or actually some little Egyptian kid found Tut and Carter found the kid and asked him where Tut was and, like an idiot, the kid told him and Carter toddled off to Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo for a brandy-and-soda.

This part of the exhibit was basically like a long round of “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow,” illustrated with brown people bearing shovels and white people bearing victorious smiles. A quote kept popping up: “According to the ancient Egyptians, a man dies twice. First, when his soul leaves his body and a second time after the death of the last person who speaks his name.” The idea being that thanks to Carter finding him, King Tut will never be dead, and also, Carter will never die either, because he discovered King Tut. A third layer of nonsense, “Guests will also discover how their presence in the exhibition perpetuates King Tut’s immortality.” I was like, hey, guys, please, please keep me out of your metaphysical circle jerk. This is between Carter and Tut.

So of course this whole time I’m like, yes, this is all wonderful, but I can’t wait to get to the gold death mask. The death mask, the money shot of the whole show, the fulcrum on which more than 40 years (in the US, anyway) of Tutmania is based, this face/object that I had dreamed of since youth.

But then, there was no death mask. There was no DEATH MASK. There was something, and honestly, I don’t know how to describe it except to say it was bullshit.

Heather went and found a guard. “Excuse me,” she said. “Where is the death mask?”

“It’s in Egypt,” he said. “It’s never left Egypt.” He was like 22 years old. As he answered, I saw that he had seriously considered getting “The fucking death mask is in Egypt, you a-holes” tattooed on his face.

We emerged from cold darkness into blazing, vivid Los Angeles. We stumbled about and soon found ourselves in a bland afterthought of a public garden.

“Your parents were heroes, guys,” Molly said. “Forty years they kept this disappointment at bay.”

We stared at sprinkler systems and shrubs until we were ready to get back in the car.

As we drove out of the parking lot, up to the parking-attendant kiosk, Heather slowed down and then stopped and rolled down the window. The attendant looked at her expectantly. Between her index and middle fingers were a few crisp singles, and she held them out to him and said solemnly, “See that Mr. Tut receives this. Tell him it’s from a friend.”