“Wenqing” (文青), a term used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China, seems to be the close equivalent of “hipster.” It’s an abbreviation for wenyi qingnian (文藝青年), a word comprised of wenyi (文藝), meaning “literature and culture,” and qingnian (青年), meaning “youth.” Apart from seeing it translated as “hipster,” you sometimes see it translated as “literary youth” or “cultured youth.”

Despite its common use, I often see Chinese-to-English translators get stuck on “wenqing.” This may be in part because Chinese-language encyclopedias and dictionaries give “wenqing” as the Chinese translation for “hipster.” But there is enough of a gap between “wenqing” and “hipster” to produce some ambiguity. The popular dictionary app Pleco gives “xiaoqingxin” (小清新) as “hipster”, and instead defines “wenqing” as “a young person who adopts an artistic or intellectual style.” A recent article on Chinese director Bi Gan’s art film, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, described a critical backlash against its rom-com style advertising campaign; here, “wenqing” was defined “artistically-minded hipsters,” a hipster subset. Which is not incorrect, either.

The origins of the term apparently go all the way back to China’s New Culture movement, with the term “wenyi qingnian” appearing in a 1928 essay by Chinese intellectual Guo Muruo in a journal of the Creation Society, a literary group co-founded by Guo. The term has distinguished origins, in other words; Guo is one of 20th-century China’s most renowned intellectuals. For example, his calligraphy adorns the northern gate of the Forbidden City in Beijing.

Young people who studied abroad introduced a great deal of new art and culture into China in the early 20th century, a period of great historical transformation known as the Republican period. This came in large part through studying western ideas in Japan, which had modernized before China.

Republican-era intellectuals had a lasting influence on the Chinese language. Their neologisms, many of which were loanwords from Japanese, ended up as permanent features. This period also saw the linguistic shift from classical Chinese to contemporary vernacular Chinese.

In particular, many two-character compounds in contemporary Chinese that refer to modern categories, such as “society” (shehui or 社會), “people” (minzu or 民族), or “modernity” itself (xiandai or 現代) were originally from Japanese (society in Japanese is shakai or 社会, people is minzoku or 民族, and modernity is gendai or 現代). These two-character compounds are of Japanese origin; even though Japan uses kanji characters originally borrowed from Chinese script, these particular compounds were introduced into China via young intellectuals who’d studied in Japan.

This Japanese influence on Chinese intellectuals of the 1920s is recorded in terms strangely similar to those describing hipsters of today. So-called Japanese “mobo” and “moga” (モボ and モガ, abbreviations for “modern boy” and “modern girl”) were known for adopting new ways of dress and behavior, interest in new forms of literature and culture, and fixation on ideas imported from the West. Yet, as with today’s hipsters, mobo and moga were criticized as decadent aesthetes, concerned with the latest fads and little else.

Maybe this set the template for today’s “wenqing.”

I’ll speak here mostly of the Taiwanese context, since this is what I know best, though there is a great deal of cultural exchange between wenqing in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China with respect to films, books, and music. Taiwan was a Japanese colony during China’s Republican period, having been ceded to Japan by the Qing dynasty in 1895 after the First Sino-Japanese War. A whole generation of Taiwanese people grew up writing only in Japanese. But terms such as “wenyi qingnian” and loanwords from Japanese later came to Taiwan in circular fashion, brought over with Kuomintang after it retreated from China to Taiwan following its defeat in the Chinese Civil War.

In the last few years, wenqing have assumed a prominent place in Taiwan. In the 2014 Sunflower Movement, when young activists were in the public spotlight, many of them were labeled wenqing. Afterward, politicians courted the youth vote and sought to make it appear as though young people were on their side. Yet politicians have also been criticized for pandering to young people.

Current president Tsai Ing-wen was criticized by Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je for “governing with hipsters” in her administration; legislator Chiang Wan-an of the Kuomintang lashed out at her for throwing around “hipster slogans” and little else. I certainly can’t imagine this happening in China, though I greatly enjoy the mental image of members of the Central Commitee of the Chinese Communist Party calling each other hipsters during their policy debates in the Great Hall of the People.

So who are Taiwan’s “wenqing,” anyway? The stereotype is that wenqing own Apple computers, like to go to independent bookstores, are always taking selfies that they post on Instagram; they hang around in fancy coffee shops, and wear tight jeans and thick-framed glasses. Perhaps not very unlike hipsters in Paris or Chicago or Buenos Aires, in other words.

I’ve observed that contemporary Taiwanese wenqing are interested in various cultural niches revolving around film, art, photography, music, or what have you. These different “scenes” can be very isolated from each other.

The music scene, for example, is very much segregated between genres. There are separate scenes for indie rock, underground electronic music and hip hop, with members of each group hanging out only with one another. And they all look down on other genres and the people who like them.

I guess that, too, is a stereotype about hipsters which seems quite applicable to wenqing: They can be unbearably snooty. The word I think most would use in Taiwan to describe hipsters is that they are ké-pai (假掰)—Taiwanese for pretentious. I can totally understand why this is derided. Wenqing are perceived to be interested in the accumulation of “cultural capital.”

For example, contemporary Taiwanese wenqing are very interested in foreign culture, usually western: foreign films, or musicians unknown to most Taiwanese. Another stereotype is that Taiwanese wenqing favor European over American culture, with the view that Europe is more cultured than America.

I think that much of the derision of wenqing comes from contempt for bourgeois values, since the West is still often idealized as superior or highbrow in Taiwan. As in, deliberately aspiring towards cultural elitism in a highly imitative fashion. It’s strangely reminiscent of the interest in things foreign exhibited by young Republican-era intellectuals or Japanese “mobo” and “moga” in the early 20th century, calling to mind the apparent origins of the term “wenqing” in that period.

Interestingly, today’s “wenqing” and their predecessors clearly share an interest in social change. Contemporary Taiwanese social movements such as the Sunflower Movement seem to be full of wenqing, hence the accusations against politicians trying to appeal to “hipsters.” Meanwhile “wenqing” activists are accused of superficiality, an aesthetic pose, an attempt to be cool—radical chic, in other words.

It’s clear that the current generation of young people in Taiwan lack the advantages that their parents—the baby boomers—enjoyed. They are surviving on meager “22K” salaries, working long hours, confronting a lack of career opportunities, and facing the fact that they will probably never own a home or have enough savings to start a family.

So this strikes me as a fundamental contradiction. Can one really have it both ways—young people are simultaneously poorer than ever, while at the same time wasting what little money they have on decadent bourgeois pursuits? This has not prevented young people from being criticized as a “Strawberry Generation“: Fashionable and chic but, unlike their boomer parents, weak and soft—like strawberries.

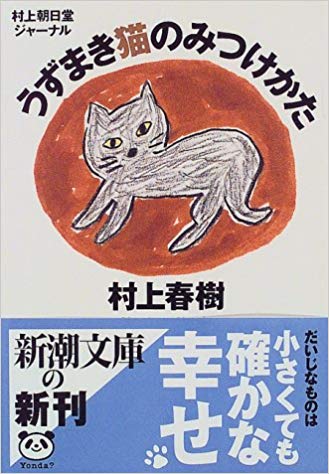

The aestheticized pursuits of wenqing can also be seen as an attempt to re-enchant a disenchanted capitalist world. There’s even a term, “small pleasures” (小確幸) referring to the trivial delights that young people cling to in a harsh world. It comes from a line in a Haruki Murakami essay, Murakami being one of the authors most popular among wenqing. As ever, art provides no shortage of “small pleasures”.

But if this is so, how do you account for young people standing up against a system that has disenfranchised them? Through, for example, the 2014 Sunflower Movement and the 2008 Wild Strawberry Movement (a retort from the “Strawberry Generation”)? While both movements were against Chinese threats to Taiwan’s political freedoms, they were also expressive of the economic discontents of Taiwanese young people against the wealthy elites of the self-interested Kuomintang.

To dismiss wenqing as just decadent and wasteful misses the point. And it strikes me as sad that some haven’t seen what should be obvious.

Music video by No Party for Cao Dong, featuring imagery symbolic of contemporary life for young people in Taiwan.

The indie band No Party for Cao Dong, comprised of former art school students, exploded into mainstream popularity in 2017 after winning three Golden Melody Awards (Taiwan’s top music awards). Before that, they had primarily been known among—you guessed it—wenqing, with their fame primarily spreading online. They are now one of Taiwan’s most famous bands. Their lyrics found resonance in society as a whole: “What I originally wanted to say, those who came for me already finished saying before me;” “What I originally wanted to do, rich people did before me,” evoking a sense of a stolen future, resulting in feelings of disgust, that “everything has become mud”, including the feelings of the heart; a stolen life, which might have otherwise produced a beautiful poem or painting. The refrain of another song goes, “I hadn’t realized, as it turns out, I was so ugly.” Such lyrics reflect the anger and despair of many young people in Taiwan, hence the popularity of the band.

Far from an aesthetic pose, on the contrary, works like this represent a scream of rage at an uncaring society. Who knows? Perhaps we should be talking about wenqing more like the “angry young men” and “angry young women,” like the youth subculture of Britain in the 1950s, more than as “hipsters.” As has been noted by others, it’s already just one step from “wenqing” (文青) to “fenqing” (憤青), meaning “angry youth”.