I doubt there is a writer anywhere in the world who can pinpoint the exact moment they started writing, largely because writing starts long before you put words on paper. However, I have been writing professionally for the past seven years—that is, being paid to write—but even then I was in university, so it was a sort of side gig. Then in 2014, it became my fulltime hustle. It is not a long time, seven years, to have been writing; it is not even a period I can say out loud in front of my peers with pride. But it is long enough for people to start asking, “so when are we getting a book?”

In many ways, writing is a kind of marriage. I have never been married before, so of course, everything I say about it I say with the full authority of observation, conjecture, and hearsay. You know how African marriages go, right? Everyone has an opinion about it. Everyone knows what is best for you – some even suggest people you should get married to. And whatever you choose, whomever you decide to spend the rest of your life with, you can never satisfy everyone. Not even most people. You can only hope to please some people (who really matter to you). And the problem is, while a good number of people will shower you with congratulations, you never know who is being genuine. That is why, in the unfortunate event this shit does not work out, people who you considered friends will the first ones to say, “Osiepa, even me deep down I knew this wasn’t the right fit for you. It is good it has failed, so perhaps try another one.”

In case the marriage works, after some time, people will want to know, “so when are we getting children?” as if that is any of their business. “When are we getting a book?” is the African literary version of “when are we getting a child?” And when you have been married to your craft as long as I have, people start getting impatient. And as people start pressuring you about timelines, the more you start looking around and wondering what the hell you are doing with your life.

“You are not getting any younger.”

“You know Ayobami Adebayo was only 29 when she released Stay With Me and you are 28 without anything.”

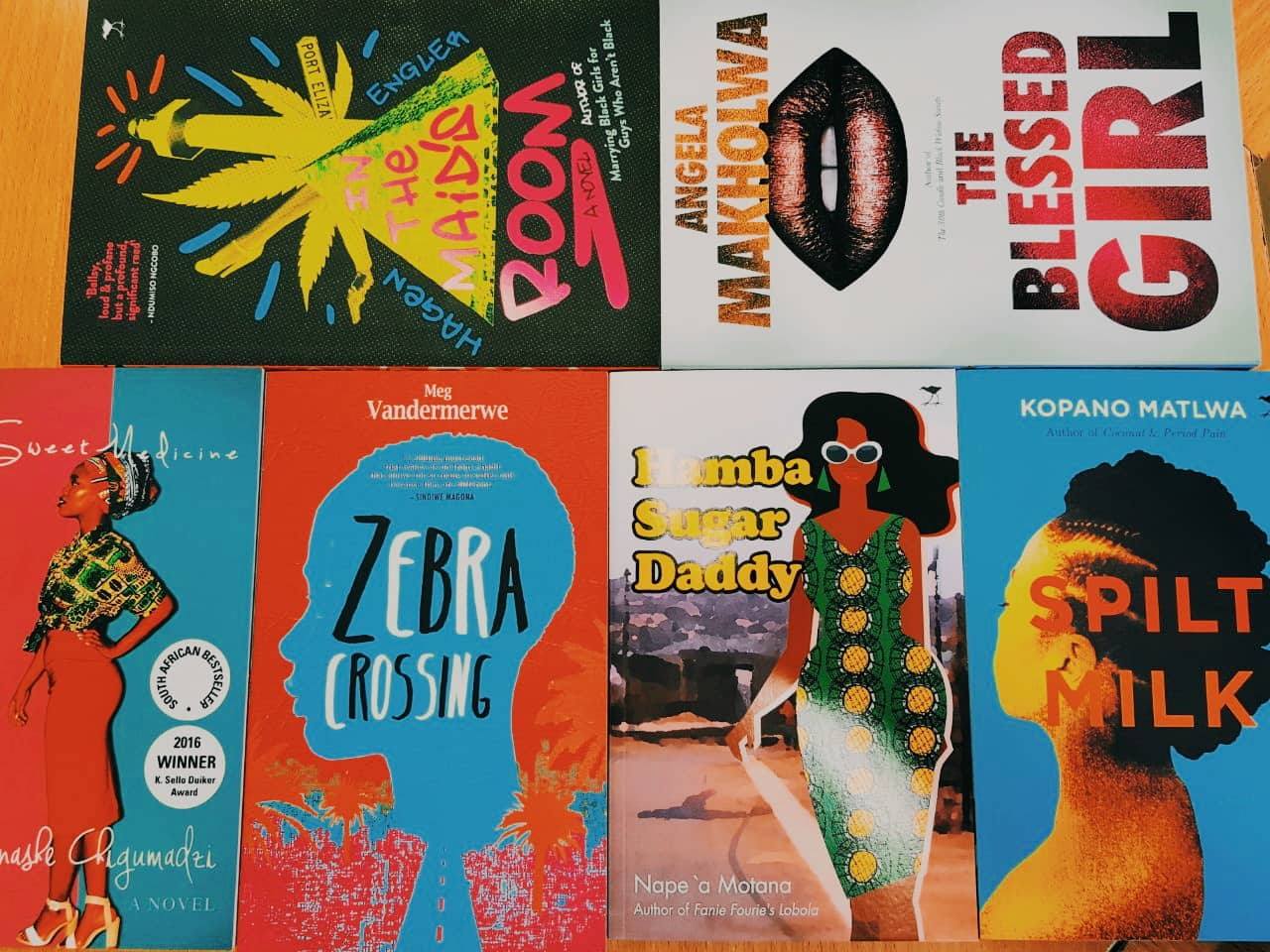

“Look at Zukiswa Wanner; in a period of 10 years, she has 7 titles to her name, and was the youngest Mandela biographer ever. You what do you have to show after 7 years?”

“See Troy Onyango. Someone who was looking up to you just the other day. He now has a manuscript and a novel.”

Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor gave birth for a second time the other day. Her second literary child, that is. I haven’t finished reading it, but it is clearly going to shake tables. Prizes are looming for The Dragonfly Sea. But as soon as the book came out, a friend posted something on Facebook lamenting about the price of books—and how ludicrous it is that Yvonne’s new book is retailing at KES. 2,800. Use Google to find out how much that is in whatever currency you understand. [About $28 USD—Ed.]

And it is instances like these that remove pressure from me about writing books—or whether I should even bother. Because you see, while I have been around for seven years, I have also been a bookseller for three of those years, and what I can tell you is this; people will give you pressure to get a child, but very few of them will want to help you raise it.

When I started the kiosk in December 2015, I was so concerned about pricing. I wanted so badly to be the cheapest bookstore around. So I cut down the margins of the books to the very bare minimum, until my other partners started protesting. Because while I would let people bargain an already discounted price, other bookstores did not. There is in fact a bookshop – the oldest one around, I believe, very rich in its collection—that sells books at KES 300 higher. Take it or leave it. Yet people still buy from them. And when I realized this I got so confused (I had not yet learned about market differentiation).

Many factors determine the price of books, especially African titles. First, outside East Africa, getting books from publishers within the continent is so expensive, we would rather just get the books from US and UK. Books shipped from UK are cheaper than those from US.

Then there are different editions and formats. And this is one of the things I never imagined I’d have to explain to customers. In many instances, when a book is released, they release it in hardcover first, then perhaps trade paperback, then normal paperback and e-books. All these are different in pricing. A hardback is costlier than an e-book, duh. Then sometimes a writer will give publishing rights to different publishers in different areas. That is why you have one book with four different covers. Just Google Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda and see how many editions are there. And for each edition there is a different price, because they are all from different sellers.

Then there is tax, transport, county government duty, booksellers’ profit and all those things added.

But you know what? Customers do not give a damn about all that. They will go online and compare prices. If a book on Rugano Books is 200 bob more than one on TBC, they will buy from TBC. And that is fine, really, I would do the same. The only problem is that some of these people will go online and start yelling Rugano are just thieves. It does not matter if the editions are different or that one person is a bigger company so they have the benefit of cheaper pricing since they buy in bulk. To a customer, whoever has a higher price is trying to rob them.

So when my friend said that The Dragonfly Sea is expensive, I tried to explain all this. But you know who was not having none of that shit? My partner, David. He basically came to that comment section and said “We cannot continue justifying the prices of books to please readers; otherwise, authors & the creative industry players will never grow! Writing a good read book is no joke, same to publishing one. If anyone values books, let them invest in them.”

Now you can see why we do not like leaving David with customers. There I was trying to be diplomatic because we have an image to protect, and then he pours sand on our name like this.

But even in his harsh tone, he was not lying. We have people who bargain for books worth 400 bob, as much as we have people bargain for books worth KES. 2,890. And if there is a way in which they can find it for free, they will. If they can find a pirated book for half the price, they will. And they will not care.

Someone will want to buy a 500 bob book for 300 bob, then go buy an overpriced coffee at an uptown restaurant to read this same book, take pictures and slay on Instagram. Want to travel to Kisumu or Mombasa from Nairobi for holiday- they will budget and book a flight for KES. 3,500. It is Saturday and there is salsa night at Serena Hotel? Sure! Entry is. 500 bob and a soda goes for 250 bob, but why not? The other day I want to surprise a girl with perfume for her birthday, and I called up five of my girlfriends to ask where they shop for their scents. You know what all of them told me? They import their scents. They wait for someone who is coming in from majuu and send them for like three bottles for like KES. 5,500 a bottle.

Of course five girls from my phonebook are not representative of how women in Nairobi spend, but it does give a sense of how far people are willing to go to get something they consider of value. So why can’t these people keep the same energy for books? Why does the struggling economy suddenly become an issue when buying books? Is KES. 2,890 expensive, unaffordable, or is it just not a priority? And how much should a piece of art that took at least 5 years to make go for?

If there is any writer out there who is struggling in this marriage like I am, please keep this in mind. If you want to get children, get them because you want to. Not because you think people will help you with them. Forget what people will say, because people will always have something to say. If you decide not to get children, they will call you a long lilo anyway. And when you do, you will still have to justify yourself and your kids.

Writers do not make people happy, writers write. If it happens to be a book, sawa, if not not, pia bado ni sawa.