In 1947, eleven years into the work of publishing books, New Directions founder James Laughlin wrote to his friend, poet Robert Fitzgerald, “I often feel like I’m working in a vacuum, or in a country where few readers hear the sounds.” He was, uncharacteristically, wrong. In a review of the A New Directions Reader, Richard Kostelanetz wrote that, “The Reader makes us wonder what the current literary scene would be like if ND had never existed.” Pointing out that Laughlin was the first person in America to publish English translations of Borges, Queneau, Eluard, and Lorca, Kostelanetz went on to wonder if, in 1965, New Directions hadn’t “outlived its purpose.”

It had not. Under president Barbara Epler’s guidance, the New Directions of 2018 is still translating essential writers into English. The global appreciation for Clarice Lispector is down to the efforts of New Directions; living writers like Beatriz Bracher, Luljeta Lleshanaku, César Aira, and László Krasznahorkai are reaching new readers because of Epler and ND.

Earlier this year, Epler and Krasznahorkai lost the Man Booker International prize to Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights, published by Fitzacarraldo Editions. Of Fitzcarraldo founder, Jacques Testard, Cahiers Series editor Daniel Medin said, “He is the best thing that has happened to the anglophone literary world in years…It’s extraordinary that his books have won the Nobel and Man Booker International within a few years of launching.” Fitzcarraldo is turning four next week, and in honor of this birthday, we conducted an email interview with Epler and Testard. They are colleagues, friends, and, in the most fruitful sense, competitors.

What was it like to be cast against each other for the Man Booker prize? I am guessing it was less like being pitted against each other and more like being cast into something together. How do you feel about prizes like this?

Barbara Epler: It was much as you say, a case of being cast together, and what good company it was! Plus, the elements of luck and absurdity about all prizes, no matter how much absolutely each author merits it, are always moving things along with a little buoyancy. It is fun to be co-hopefuls around a Prize. I don’t feel the love I have for my tennis partners, but there is some of that rascal camaraderie of competition.

I love prizes. Books need every friend they can get to raise their heads out of the madding crowd. I also love prize stickers–the inner raccoon loves a shiny object.

Jacques Testard: It was daunting, and flattering, to be in such illustrious company. For such a young publishing house–we published our first book in August 2014–it’s quite surreal to be invited at that top table, not only with New Directions but also with MacLehose Press, Serpent’s Tail, Tuskar Rock, Oneworld. I don’t know about Barbara, but at the prize galas I tend to be a nervous wreck–the stress really gets to me. I suppose that’s because I know how transformative winning prizes can be for Fitzcarraldo Editions. It’s not quite make or break, but it’s one small step towards long-term financial security.

Tynan Kogane (New Directions, editor): Of course, we want all of our authors to win all of the major prizes. But the lack of control that publishers have in who eventually wins them can be a little liberating and fun. Only last year, we were both rooting together for Mathias Enard’s Compass to win.

From the stage of choosing which books to publish, there’s often the excited exchange of emails asking, “Have you heard about X yet?” Sometimes it can feel like two detectives working on the same international case. With Maria Stepanova, Nora was wise enough to know that we’d both be very eager to pounce upon a Sebaldian novel about Russia’s cultural memory. In the end it was an easy decision that led to the perfect outcome. Later on, having two editors looking at the same manuscript can be extremely valuable–two sets of eyes catch much more.

How does something like co-publishing the Maria Stepanova book work?

BE: There is much back-and-forth. I saw with Tynan and Jacques how well they edited Mathias Enard’s Compass, and I know with Maria Stepanova there will again be this doubling of intelligence for the editing, care and presentation of the author. It is especially good when a book is launched both in the UK and the US, another doubling.

JT: In my limited experience, publishing a book simultaneously in the UK and US is always that little bit easier. Both publishers are able to feed off each other’s energy, and it helps to have press on both sides of the pond simultaneously.

The Maria Stepanova book came about in quite a fun way. I saw Nora Mercurio, the rights director at Suhrkamp Verlag, in London last March. We talked about the Suhrkamp authors we already publish–Rainald Goetz, Esther Kinsky–and at the end of our meeting Nora said, “I just have to mention this one name, otherwise you’ll kill me later: Maria Stepanova.” That night she wrote me an email to say she had an offer from a publishing house in the US. I wrote to Tynan, hazarding a guess that it might be New Directions, and it was. So we talked about the book, swapped intel, and eventually proposed to Nora and Maria that we’d publish the book together.

How do editors all over the world differ? Are there differences that spring to mind?

BE: Editors differ from office to office, even in a small office such as at ND. And that’s a good thing. I do think some countries edit less and some more, but again that would be true within companies, too. This might be one of those cases of “comparisons are odious.”

JT: Editing books isn’t something you can really teach: it’s sort of intuitive, entirely subjective, and like most things the more you do it the better you become at it. And though I know plenty of editors around the world, I have no idea how most of them edit, because it’s quite hard to talk about the nuts and bolts of editing (and besides, talking about books is more interesting). I have worked closely with a few editors in the US but it’s only ever been on translations, where the editing process is fairly limited in that you’re making a version of something that already exists rather than helping to fashion something from scratch. So I have no idea, really, other than an intuition that every editor is different.

Translation is such a huge part of what you both do.

BE: As a person with no ear for languages, and as a monoglot, what I most feel about translation is an overall gratitude.

This magic of being able to understand all these languages always reminds me of the Grimms’ fairy tale about the white snake. The enchantment and generosity first of the hero (well, not to his poor horse, fed to baby ravens, but to all the other creatures he meets) and then the generosity in return of all the animals, based on the harmony of understanding, really based on the knowing–that’s translation.

Of course, first we need great books to translate, so there is also a first gift: the book in the original. To me, the devotion of translators is quite amazing.

JT: I was lucky enough to grow up bilingual, reading in both French and English, and often reading in translation without really considering there might be any difference with a text written in the original language. Ever since I started editing, whether at the White Review or at Fitzcarraldo Editions, I’ve wanted to publish literature in translation. It only seems to be in the Anglosphere that translated literature gets set apart from English-language literature, that it gets its own shelf. In France, where a fifth of all books published in 2017 were translations, you’ll find Balzac and Borges on the same shelf in bookshops. That’s the way it should be–it’s all just literature.

Do you ever think about spreading out your titles, geographically? If you publish a title by one Korean author, do you worry about then “doing” Korea twice in a year? Do you ever feel like you need to look into certain countries more, if you’re not publishing many authors from that country?

BE: Sometimes we think of this. Last week, we were putting a new list together–we now, hideously, have three a year instead of two–and we thought, “Let’s have the Urdu book from India on this list and then the Bengali book on the next one.” But that choice was made more with a view to presentation. It is all about considering how best to have a solid attention for each with the reviewers and booksellers, as they are seeing hundreds of thousands of books annually, and I can’t believe their eyes aren’t rolling in their heads.

We don’t really plan. It is more of a seat-of-the-pants sense of trying to have a memorable and an easy-to-thumbnail-sketch pitch list as we want to present the books clearly to people whose time is already being eaten alive.

As to the second part and certain countries: we go on jags.

Spanish-language has been steady for us, for the past 15 years or so. You get to know people and know more books that ought to be in English, books which sound incredibly good and which we might do well by. We have been on a little Japanese spree lately, but we try to publish from all over.

We are very feeble about Africa, except for North African authors, and weak on the many languages of India and Southeast Asia (though we do have great recent books from the latter two). We also have almost no Native American writers, and one of the very best books I’ve read–Carpentaria by Alexis Wright, an aboriginal writer of real genius–I missed out on publishing. But we are looking, always.

The fact is that Europe and males are in the house in a predominant way, but we want to see changes there, and I think we will. In fact, we have been changing that.

I always think there are so many astonishing things waiting to be found and that, fair or not, it is a boon to New Directions that so many things haven’t been brought into English, largely because of the old publishing model in the US. Until recently, only odd, smaller trade publishers like New Directions or Grove were active with translation. There was the rare exception like Harcourt, and university presses such as Northwestern and Texas, which all did so much, but in terms of the big houses which bring out most of the books in the USA, very little translation was being carried out by American publishers. Knopf might have done a bit, but there really wasn’t all that much.

The good news is that now there are so many presses even smaller than us that are bringing home treasures, and they are new–most didn’t exist 15 years ago.

Which brings us back to friendly competition.

JT: We’ve only been publishing since 2014, so that question isn’t quite as relevant to Fitzcarraldo Editions as it is to New Directions because we’re still very much building a catalogue from the ground up (and we are one of the smaller presses Barbara mentions). And in fact our problem is more one of size. This is either naive or idealistic or stupid–I refer you to the name Fitzcarraldo, a not-very-subtle metaphor on the stupidity of setting up a publishing house, like dragging a 320-tonne steamboat over a hill in the Amazon jungle–but I want to be the kind of publisher that publishes authors rather than books. So if I publish your first book in English and it sells 500 copies, I will publish the second one anyway, and so on and so forth. I’ll have taken you on because I believe in you as an author, and the hope is that author and publishing house can grow–and prosper– together.

This is a problem in terms of expanding our catalogue because we remain a tiny operation (two full-time staff including me, and two part-time) with 11 books published in both 2017 and 2018. A significant proportion of those books are new books by authors we already publish. This year it’ll be more than half of our output, with new books by Brian Dillon, Alejandro Zambra, Joshua Cohen, Olga Tokarczuk, Dan Fox and Mathias Enard. So while we are always looking for new authors, we are limited in the number of books we can acquire and publish for now.

Generally speaking I have no problem with publishing a number of authors from the same country. I’m naturally drawn to French-language authors, and we already have four on the list: Mathias Enard, Jean-Philippe Toussaint, Annie Ernaux, Jean-Baptiste del Amo; I don’t read German, but we have five German-language authors already: Gregor Hens, Clemens Meyer, Rainald Goetz, Esther Kinsky and Elfriede Jelinek. All of them are ambitious, innovative contemporary writers who play with form or style or both, and that’s what drew me to them.

It’s quite rare that I do decide to go in search of an author from a specific country or region. I went looking for a Polish writer in the wake of the Brexit vote, when there were attacks on Polish migrants in Britain. I felt I had a duty as a publisher to fight against a difficult cultural climate, that we needed more Polish voices, and an insight into Polish culture in Britain. I didn’t have to look very hard, as Olga Tokarczuk turned out not to have an English-language publisher (as seems to be the case for many of the world’s best writers).

At the moment, our translation list is very Eurocentric, with only two Latin American writers (Zambra and Fernanda Melchor, another writer we share with New Directions), and we’ve just signed a Palestinian novelist, Adania Shibli, whose novel Minor Detail I’m very excited about. Slowly but surely we’ll open up to other parts of the world–that’s the hope.

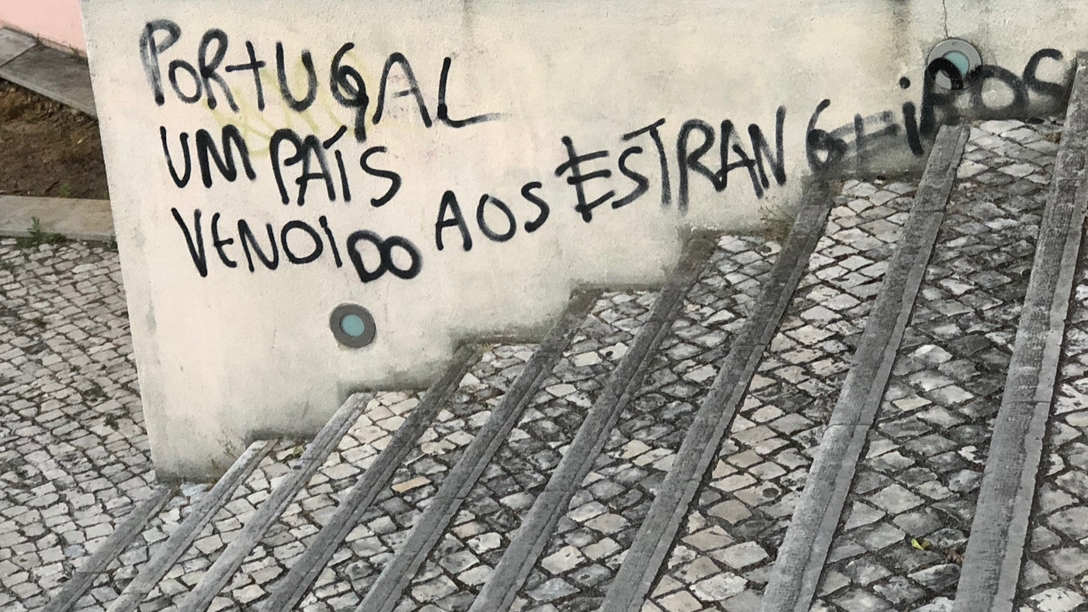

I was just in Lisbon, and spoke to some of the researchers at Casa Fernando Pessoa. (New Directions released the Pizarro/Costa complete edition of The Book of Disquiet.) Pessoa was not in any way a traditional author but he is a hero in Portugal, taught in schools, a face on the now-defunct 100 escudos note. In Anglophone countries, one scholar told me, he is not nearly as important as he is elsewhere in the world.

How does it feel to help change the idea of literature itself, with someone like Pessoa? Or is that perhaps itself a stupid idea, changing the framework? If the canon is local and multiple, then change is a different process. Or, to reverse slightly, are there other authors like Pessoa, writers who can change the idea of the canon itself, authors whom English speakers are the poorer for not knowing? I know the answer to that is “Yes, the list is vast,” but I suppose I am thinking of figures who have the ability (as Pessoa did) to change how the canon is consumed, and viewed. And as much as we may hate the idea of a canon, it seems unlikely that it will disappear as either fact or idea.

BE: I think Pessoa may be a hero in Portugal the way Clarice Lispector is a hero in Brazil, Emily Dickinson is a hero in America, Borges is a hero in Argentina, and James Joyce is a hero in Ireland? By which I mean they are as much foundational figures as demigods. We don’t hope to re-create their home-team divinity, or foundational status: I guess we just try to get great world writers out of the grad school literature programs and into people’s weekend bags.

But, that said, I would venture that Clarice Lispector “helps change the idea of literature itself,” as you say–and Borges and Kafka (everyone’s hero) definitely did, too. Thank god they are in English: imagine if they weren’t, what poverty.

And I don’t think it’s stupid to talk about changing the framework when such writers certainly have.

A Japanese friend recently was telling me about her fascination with Hamlet being staged (and changed) in all these different languages.

But we are a little closer to the ground, busy scratching around. If we can get people to get a taste for Pessoa–It’s as if someone were using my life to beat me with–we’re happy. We love him and have four more Pessoa volumes coming, though my feeling is The Book of Disquiet is the one most likely to find the most readers.

JT: Fitzcarraldo Editions turns four years old on 20 August, 2018. In that short time we’ve published 38 books, all of them by contemporary writers. I don’t think we’ve come close to changing the idea of literature itself in our publishing choices, whereas New Directions have legitimately been shaping the canon since 1936. That kind of longevity as an independent publisher is something to aspire to. But I don’t think we’ll ever come close to having a list quite like theirs, even if the company makes it to 2096.