The Movie Girl

In October 1996, I was 27, a freelance film reviewer at Philadelphia’s second best (of two) alt-weeklies and excited to see and review Anthony Minghella’s The English Patient. My excitement was not about the movie itself, which I was pretty sure would be mediocre, but about its female star, Kristin Scott Thomas—then to me the apex of beauty—and the knowledge that for some significant portion of three hours, I would get to look at her newly blonde hair.

During my time at this paper, I wrote three to four reviews a week: two short reviews and one or two long ones. Most of my reviews were negative, bordering on mean, for the simple reason that most movies are not good. But I still loved movies, and I had the highest, purest hopes for them. I wasn’t exactly quivering with anticipation when the lights went down before Powder or the remake of Sabrina, but for most films, I retained a childlike faith that I was about to behold greatness.

So, when Braveheart, Toy Story, Shine, and—God help us—Swingers (!) were not great, I said so. Honestly, all I really wanted was to see a decent movie, and once in a while—Trainspotting, Bound, The Long Kiss Goodnight, The Daytrippers—I did. My bad reviews were angry. But they weren’t about rage. They were about disappointment.

For short reviews, I was paid $75. For longer ones, I got $125. Sometimes I interviewed people—like Kenneth Branagh (effusive, delightful), Lili Taylor (defensive; my fault), or John Sayles (pompous ass; his)—and got another $75. I think I made about $1400 a month, or $1600 if I was very lucky, but I didn’t mind. I could live off it and I spent all my time writing about movies.

Sometimes, when I met people, they’d say, “Wait! Aren’t you the movie girl?” Sometimes they would say, “Do you like anything?” A guy in a bar told me once that he and his friends called me “the movie assassin.”

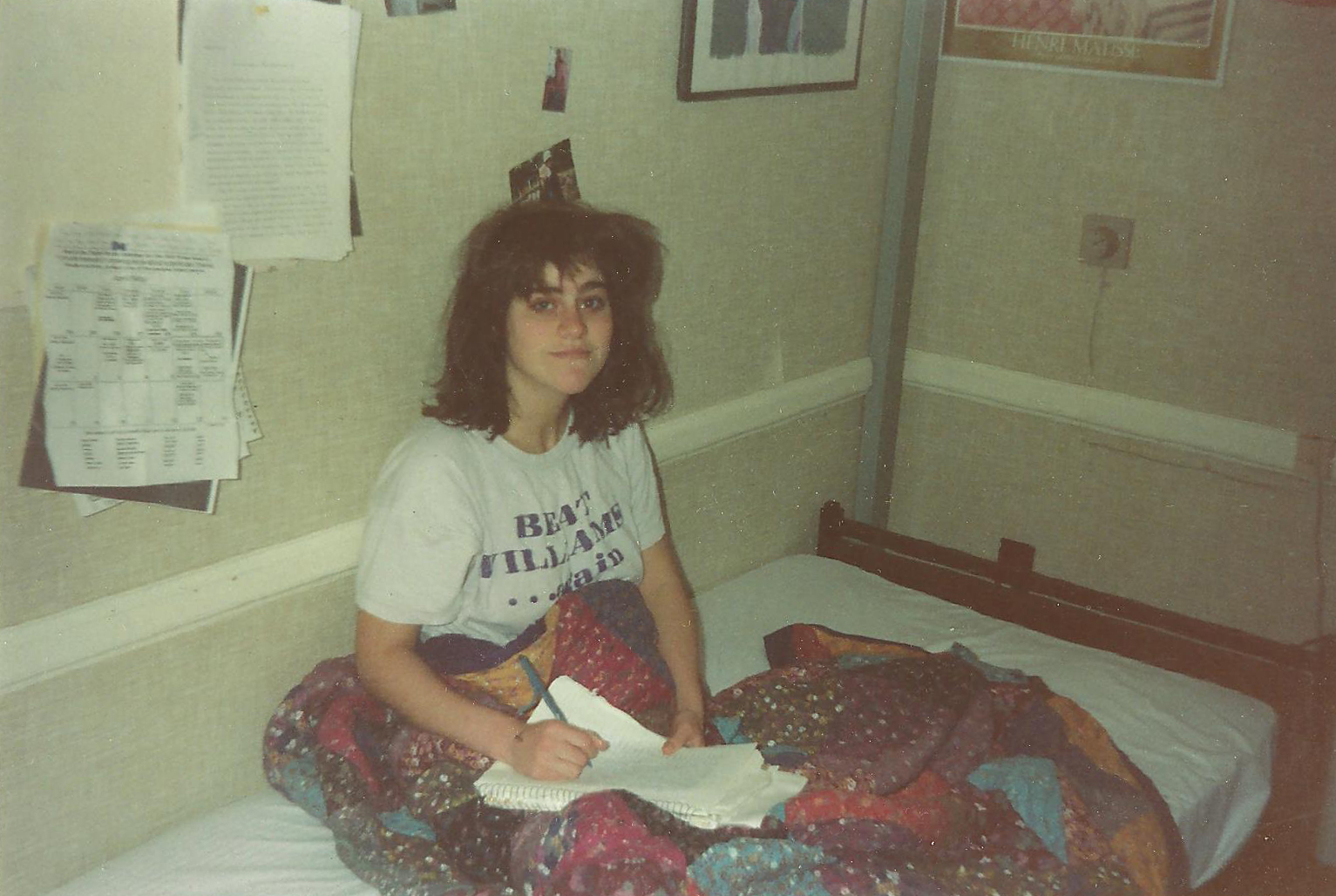

Juvenilia

I lived a modest, pleasant life, but what I wanted was to be hired. To be On Staff.

The editor of the paper, Ron, was in his late 40s. His sidekick, Julie, the managing editor, was my age. They were both so boring we didn’t even wonder if they were screwing. They knew I wanted a job, and it was unfathomable to me that they wouldn’t give me one.

Sheila, the calendar editor, was my best friend. Sheila was such a fucking bitch it was awesome. She was also the only person I have ever known who truly supported my being a bitch to the true extent of my capabilities. We read Ron’s and Julie’s weekly columns out loud to each other, laughing so hard we peed Chesterfield Ale into our underwear. I veered back and forth between being certain I would never be hired and being equally certain that I was one perfect review away from a job, from writing something so good that Ron and Julie, who I felt held all the keys to my future, would be unable to refuse me. I spent about half of my time complaining, feeling sorry for myself, and just basically being a jerk with Sheila. For the other half, I worked. I lived on the eighth floor of a beautiful building and split the $700 rent with a vixenish college sophomore named Danielle who made me feel mature. I looked out over the lights of the city and wrote and lost track of time.

Every Monday, I walked the half mile or so from my apartment to the paper’s offices to deliver my copy via a floppy disk tucked into my jacket pocket. As I walked, I would play sentences in my head, laughing at my own jokes, awestruck by my own profundity. It is nice to love what you do, and to be properly compensated, and praised. It is not nice to feel the opposite—wronged and ignored, sure you’re on the brink of a breakthrough and also sure it will never come—but there was a buzz to it all too. I was the pearl, they were the swine; not wholly unenjoyable!

Each week that passed I wrote something amazing and nothing happened, so I dug in and wrote harder. I thought I was trying to get somewhere. I thought there was somewhere to get. I had no idea that what I was experiencing was being a writer, and that no matter what happened, good or bad, I would feel exactly the same way forever.

Jennifer

For the first year or so I worked at the paper, Julie edited me. She basically fixed tiny errors, and cut small tangents and good jokes. In tiny, pathologically neat script (this was pre–track changes, I think) she wrote “unnecessary,” or “???” Sheila cut Julie’s photo out of her weekly column and taped it to a ruler to make a Julie puppet. “Me no understand movie joke,” the Julie puppet said. “Me go have salad.”

I’d heard they were going to hire an editor just for the arts section, and had even thought it might be me, but when I asked Julie about it there came over her face a look of such astonished horror, as if I had invited her to go on a full-moon squirrel hunt in Rittenhouse Square. I was told they needed someone with experience. Well, fine, I thought, perhaps this new person will be my ticket.

When they finally did hire someone, she called me in right away for a meeting. Jennifer was 10 years older, six inches shorter, and wearing a blue polka-dotted dress and slingback tan heels. Right away, she mentioned that she went to Penn, and she seemed both embarrassed and proud of this. She had enormous eyes, and I had a little trouble getting my bearings not because she was so pretty—I mean, she was, but that wasn’t it—but because she was so intensely feminine. After a minute or so I was able to actually hear what she was saying, which was that she thought I was “extremely talented.” I had heard that before, but only in school, never from someone who would pay me. I nearly threw myself at her feet and sobbed—finally, someone else who agreed with me.

Within a month, we’d had dinner or drinks at least six times. I discovered that she knew Ron from some long-ago job. She wouldn’t say bad things about him but she laughed heartily at the bad things I said.

Jennifer came from a strange family. They were so strange I couldn’t even wrap my mind around what brand of strange they were. Having come from a stable family I envied her having a specific reason to not feel right with the world. She dispensed wisdom, and I dispensed jokes. I listened attentively, she giggled into her hands. I told her my life story: high school, college, now. She told me hers, which was longer, and therefore more sad.

Her ex was a successful writer living somewhere else. I asked her why she left him. “Because he was an idiot,” she said.

“An idiot? But wasn’t he a very good writer?” I asked.

She laughed so hard her eyes teared up. “Oh, my dear,” she said in a tone of voice I loved, because it assured me she was going to help me grow up.

Jennifer knew a lot, and it concerned her that I knew so little. I brought a magnum of chardonnay to her house once for dinner. She put it in the linen closet and we drank her wine instead. I said I felt guilty, and she said, “I’d make you feel guiltier if we drank your wine.” When she went out of town I injected her fat orange cat with insulin, slept in her real bed, and enjoyed it enough that I replaced my futon. When I got pregnant, she said “Yikes,” handed me $40, and said, “Take yourself out to dinner afterward.”

My age made her protective of me. Her size made me protective of her. I often have this thing with small, feminine women. When I am alone with them I try to deduce whether I would be strong enough to carry them if I had to. I look for exits we could escape through if attacked, and case public spaces for men likely to become suddenly violent. Jennifer was my boss and I wanted things from her, but when we were out, all our interactions were undercut by the sense of responsibility I felt for her physical safety.

I lived for Jennifer reading my reviews when I brought them in. She took my disks from me like they were wrapped gifts, and settled in at her desk like a hen settling over eggs. Then there would be murmurs of appreciation, giggles, sometimes howls of laughter. Walking to the office I still ran sentences by myself, for my own keen appreciation, but the more powerful fantasy now centered around Jennifer: what she would agree with, what she would laugh at, what would make her cry.

The English Patient

On an October afternoon, walking across the park with reviews of Sleepers (no), The Ghost and the Darkness (no), and Breaking the Waves (a yes that years later became a no), I was in a very good mood. I was so happy about my work that upon finishing it the night before, I had summoned Danielle from her room to join me in choreographing a dance to Folk Implosion’s “Nothing’s Gonna Stop the Flow.” As always, I was looking forward to Jennifer reading my work. I was in such a good mood, and, like most people, in this state I am apt to say the wrong thing, and in my defense this is why I told Jennifer that I could not wait to review The English Patient because it was going to be so terrible and stupid but Kristin Scott Thomas was in it and she had blonde hair and therefore I was also dying of anticipation.

“That’s why you want to review The English Patient?” Jennifer said. “Because of some actress’s hair? But you think it’s going to be awful?”

What a fool I was. If I had managed to think for one second about what Jennifer was like, and that she was also MY BOSS, I would have known to keep my mouth shut. Yes, at times Jennifer admired my irreverence and bluntness. Like when I went to a Chasing Amy screening and Kevin Smith mocked this gay dude I knew, and I stood up and called him a homophobic asshole, Jennifer was thrilled. “I wish I could have done that,” she said. But that was Kevin Smith. To her, he wasn’t a “filmmaker.” He wasn’t “culture.” And so yes, insulting him was fine. But making light of a Film and saying I only wanted to see it because of Hair landed me in that part of Jennifer’s mind which regarded me not as fearless and passionate but as childish and unrefined. She felt it was her job to correct this. More importantly, she was the Boss and had to have Standards.

Anthony Minghella’s The English Patient—based on an award-winning novel, sumptuous foreign setting, somber themes of war and infidelity—was not something Jennifer wanted me to joke about.

“If you’ve already decided it’s silly, I really should send someone else,” Jennifer said. “People are saying this is a really wonderful film.”

What people? I thought. Fuck those people! I felt the day, my $125, and my chance to hold forth on the most anticipated movie of the fall, slipping out from under me. I backpedaled. “I am not saying I’m positive that the movie is going to be bad. I mean, I give everything a chance.” I was sure I’d given her my bullshit speech about how I just wanted movies to be good.

But she had moved on from me. She was calling the man—the man!—she had review movies sometimes. He lived in New York. He was a professor. She was dialing his number. To borrow a phrase from that time, and the theme of this essay, this aggression [would] not stand, man. My adrenaline was high, my anxieties multifaceted, but my biggest fear was Jennifer thinking there were things I couldn’t write, that some assignments were beyond me. If she wanted me to go to see The English Patient through a lens of reverence, surely I could borrow that lens for one review?

That’s when I said, “Well, I read the book, and I really liked it.”

“You read the book?” she said. Her nostrils flared coltishly. “I keep meaning to but I haven’t gotten around to it.”

“Yeah,” I said. “It’s—really . . .” I almost used the word moving, but that would have been overkill. “It’s just—very well written, so, I guess I thought—I—well, I mean, I guess when I said the movie was going to be bad what I mean is that—What I was trying to say is that it’s probably not going to be as good as the book. That’s really what I meant. Because I really loved the book.”

I was shocked that she believed me. But why wouldn’t she? Lying is not hard. All it requires is the nerve to say things that aren’t true, while remembering that even the people who know us best are rarely paying attention.

Sam

I saw almost every screened film sitting next to the same guy, a film critic at the other, better, weekly. Sam was four years younger than I was, and I felt he should look up to me but he so didn’t. He was more of a film person than I was. I was really just a writer who liked movies. Other than reading maybe twenty Pauline Kael reviews, I didn’t know shit about film. I kept saying I wanted to know more, but the amount of time I spent reading about film or watching old movies—zero time—meant this was not true.

Sam, who did not tend toward self-doubt, loved a lot of movies I found dull. He loved Godard, who I might have had opinions on had I ever actually gotten through anything. I loved a lot of movies Sam found really basic, like The Saint, Jerry Maguire, and The Long Kiss Goodnight. We were united in our general dismissal of sentimental foreign movies like Life is Beautiful, and the Czech fake-fatherhood weepie, Kolya. We’d recently butted heads over F. Gary Gray’s Set It Off, which I thought sucked. He had liked it, but that wasn’t the problem. The problem was that he’d said “the filmmaking was interesting,” and that made me feel insecure, like he could see things I couldn’t. On the other hand, I didn’t even want to be someone who thought Set It Off was “interesting.” I mean, if it’s raining, you don’t need meteorology books. You need an umbrella.

The English Patient, based on the 1992 Booker Prize–winning novel by Michael Ondaatje (and it actually won ANOTHER big new special-anniversary Booker Prize just this year because one can never have too many) takes place toward the end of World War II and centers around an English patient (Ralph Fiennes), who is maybe not English, and is possibly a spy, and his slow death in an abandoned Italian villa from terrible burns sustained in a terrible plane crash. Much of the story draws on memories of the man he was before this tragic event. Pre-burns Fiennes was having an affair with Kristin Scott Thomas, who died from injuries sustained in a different plane crash. He was also apparently quite the scholar. His demise is attended by a pretty nurse (Juliette Binoche) whose ignorance is the perfect foil to his genius, which, unlike his face, remains intact. Binoche fusses over Fiennes while bubbling over with guileless inquiries like, “Who is Herodotus?” Through hideously blistered lips, our dying brainiac slowly croaks out, “Herodotus . . . is . . . the father . . . of history.” Duh!

The movie seemed very clearly bad. Binoche tittered with rueful appreciation as her patients sexually harassed her, peeled a plum with her sexy teeth, and—because what’s hotter than an irrepressible spirit during war—tickled out Bach on a bomb-damaged grand piano. Meanwhile, post-burns Fiennes refused to let his physical deterioration interfere with a compulsion to offer unsolicited literary advice like, “You have to read Kipling slowly, your eye is too impatient.” This particular gem was delivered to Kip, a Punjabi Sikh played by Naveen Andrews (Sayid from Lost) who, no doubt, had waited his whole life for French Fry Fiennes to coach him on this very topic!

There I was sitting next to Sam, watching this movie that sucked in exactly every way I expected it to and then some. Imagine my horror when it seemed to me that he liked it. This was unfathomable, but we generally passed the time in bad movies whispering snide comments to each other, and he was just watching the movie.

Pre-burns, flashback Fiennes stroked Scott Thomas’s hair, which—thank you for asking—was stunning. “Let me tell you . . . about wind,” he whispered to her. I longed to lean over and whisper to Sam, “Oh, that’s OK, I’m pretty sure I know what wind is!” but I did not dare disturb him.

I endured a whole hour before we got to the film’s most excruciating moment: Juliette Binoche, lounging next to her singed charge, reading his very own words aloud to him from a journal, or a letter, or a parchment Post-it tucked into his leather bound, cum-stained, volume of Herodotus. “The heart is an organ of fire,” she reads. She smiles wistfully and says, “I believe that too.”

Sam leaned toward me. With all of Binoche’s unrivaled jouissance and then some, he whispered, “So I guess you were a pretentious douche before you were consumed by a giant fireball.”

“You don’t like it either?” I asked. I was so happy.

“Jesus, God, no,” Sam said. “It’s awful.” The patrician authority in his voice, often maddening, was like a balm.

The English Patient II

My review of The English Patient was not really a review. I began by extensively praising Kristin Scott Thomas’s hair, and used this as a way to transition into discussing the other good things about the film. One was the chance to see Naveen Andrews, who I had liked so much in The Buddha of Suburbia, which I spent a paragraph praising, and which, I stressed, had a good story and was actually about something—unlike The English Patient, which was about British people fucking in their colonies, and not nearly often enough to be any fun. I recounted the moment when Fiennes stuck his livery tongue into the alabaster hollow of Scott Thomas’s throat, and Sam and I cried out in unison, “Ewwww.”

It was the best thing I’d ever written.

I pretended to read the paper as Jennifer read my review. I waited for her to start giggling and making appreciative sounds. But she was silent. When she finally turned to speak to me her face was white. She said, “Sarah, we cannot print this review.”

“But the movie was really, really, bad,” I said. “I mean seriously, it was the worst.”

“That is not the consensus from people I know who are smart,” she said. She was pretty mad.

“I swear to God that no one could possibly like this movie,” I said. “I mean, anyone who likes this movie is an idiot.”

She listed a bunch of people she obviously thought were not idiots who liked it. I knew who, like, two of them were. I didn’t have much to say about them except I would have taken their yearly incomes over mine. The moment now strikes me as so incredibly East Coast—this notion of consensus—which I would later run away from, and then, in a strange way, miss.

She rolled her eyes at me. “You cannot write a review of one of the biggest films of the year that does not even attempt to discuss the film,” she said.

“But that’s the whole point,” I said. “I mean, the movie is like, ‘I’m serious, I’m serious!’ but it’s such a total piece of shit. Plus, the thing I wrote was like a thousand times better than anything that’s been in this paper, ever.”

This was not a good thing to say. She’d been holding back a bit, but now, she was really mad at me, and didn’t care if I, or the other people in the office, knew it. “Oh boy,” Sheila said, and slithered out, as Jennifer listed all the people who wrote for the paper who she, in fact, thought were more professional, more knowledgeable than I was. The word adolescent was used. Winding down, Jennifer said that she had a section to put out, had already spent too much time talking to me as it was, and that she was going to get someone else to review it, and she had to find them fast.

“No,” I said, “Please don’t. I’ll do it. I can—do it again. I can do it better.”

I could see the wheels turning in her mind. She was mad, but she also needed this problem to be solved, and it was better for her if I solved this problem right now than if she spent all day on it.

“You read the book,” she said. Her expression and tone reminded me of someone remembering the combination to a long-locked safe. “You could write a review comparing it to the book.”

I forgot I had told her I read the book.

“Look, it’s not that I mind if you criticize the movie. I really don’t. I just—I just really feel that we need to take it seriously.”

“Don’t worry,” I said. “I’ll do it the way you want.” I felt that everything rested on this. I was not wrong, but I was wrong about how.

The English Patient III: Reckoning

I was going to have to see the stupid movie again. Once I started thinking it was dumb I had stopped taking notes. (This could be my epitaph.)

The only screening left was at night, way out in the suburbs. I would have to take a train and then walk along a highway to get there. “Didn’t I see you at the morning screening in town?” the publicist asked me when I called her about seeing the movie again. She said she didn’t blame me, wasn’t it magnificent? And that Ralph Fiennes—what a dreamboat! “Before or after the plane crash?” I asked.

I tried to find a copy of The English Patient in a used bookstore, but couldn’t, so had to buy one new. It was $12 or $13, a fortune. I sat through the movie again and took real notes with a lighted pen. I read the book on the train, there and back. The first page let me know what I was in for. It featured the word aubergine where purple would have done, and went on like this.

The English Patient is probably not a bad book, but its ostentatious sensuality was extremely not my thing. For one night and a whole long day I choked down its perfumed gruel. Then I began my new review, which took three entire days and nights. I had never committed such a sustained lie to paper and it was a weird process. It was like fishing in an area that’s been overfished, or sweeping a clean floor.

I didn’t go so far as to say that the movie was great, but I know that overall I ended up recommending it. I may have praised the cinematography and the performances. I probably used cartography metaphors, because Liver Tongue Fiennes was a cartographer, and cartography is Culture. I probably said that the movie could not hope to equal the lyricism of the book, which everyone else would see as a compliment, and which I, with private knowledge of my personal dislike of lyricism, clung to as a moment of resistance.

Jennifer read it, her expression calm but grave, like a doctor taking the pulse of someone who isn’t going to die right away, but won’t be getting better. As I left she gave me a curt nod and said, “Good work.”

From my very first Thursday as a movie reviewer, I’d had the same routine. I would wake up early, excited, and pick up my paper from the yellow box on the corner of my block. Then I went to read it in a bad café, where I drank Earl Grey tea out of one of those hideously oversized cups that were popular in the ’90s, and felt very satisfied. I did not do that the day my review of The English Patient came out. I never looked at it. Every time I thought about the fact that other people all over the city were reading it, I would shake my head and try to think about something else. When I walked by the theater and saw people in line to see it, I felt sick.

But then two weeks passed, and the check arrived. I remember looking at it and seeing the itemized list of my contributions: $125 Set It Off, $75 The Crucible, $75 101 Dalmatians, $150 The English Patient. She’d added extra money because I had read the book. I wept, but at this point, it was because I was actually proud of myself. I felt I had learned something about how adults take care of themselves.

A few weeks later I brought up to Jennifer the idea of getting on staff. “Sarah,” she said. “They are never, ever going to give you a job here.” Her tone was cold, but her purpose was not to be cruel. It was to be understood.

Success

Almost a year later, an editor at the fancy magazine I’d been pitching over and over finally got in touch with me. Something miraculous had happened. Her boss had barged into her office that afternoon holding the pitch I’d just sent to her, which he had somehow intercepted. He was shouting, “Why isn’t this girl working for us?” The next day I took a train to New York. They took me out to lunch in SoHo. When they went to the bathroom I snuck a peek at the label of the big editor’s coat. It was Prada. I fingered the label to see if it was sewn in, but the stitching was tight. They told me they wanted me to write a sex column and I said I would.

I had no particular interest in writing about sex and in fact found it embarrassing. But soon this was my job. I moved to New York, and rented a nice apartment, and had a lot of nice clothes. I ate out whenever I wanted. I assumed this was what I was supposed to be doing. It was crazy to get checks in the thousands and not the hundreds. Nothing had ever felt better. I knew there were people who made money saying things they thought were actually true, or important, but I figured I wasn’t good enough to do that, because otherwise, people wouldn’t keep asking me to write stupid stuff. I went to Europe for the first time ever. Then I moved to Los Angeles and got a book deal, totally by accident, writing two novels I didn’t really care about.

I bought a house, and I felt like it was enough to call myself a writer and to dress like I was interesting and to then therefore be interesting, but I was just a checking account with shoes and bookshelves. Then, starting one week in 2008, and moving rapidly from there, I lost my house, print died, and my life as I had known it was over. I was 40 and poor. The only sense I had of mattering involved being asked to write things and being paid for them, and now that was gone.

I thought a lot about my lying review of that racist, boring, laughable, pseudo-intellectual movie. I thought about how at the time, I was proud of myself for having the courage to make shit up because I was afraid to disagree with someone I wanted to impress, and also afraid of not making money. That one decision had led to a lot of other similar ones and had eventually ended up as an agreement with myself to spend over 10 years of my life being a different person than the one I had planned on being and feeling smug about being good at writing crap and then even actually starting to think the crap was good because of the money I was given to produce it. I look at all the people in tech who are convinced they are saving the world, that what they do matters. When the money goes, and it will, that feeling will go with it.

If you write thousands of sentences that have absolutely nothing to do with what you think or feel those sentences are still what you will become. You can turn yourself into another person. I turned myself into another person.

That person was very sure she understood the way the world worked. If she met a writer who was unsuccessful, she always thought, “Oh, they are either extremely untalented,” or “They are still trying to be themselves—what an idiot.” When everything fell apart, this person was incensed she could no longer make lots of money for saying incredibly stupid things. She thought about killing herself all the time.

I used to think I thought the right way, like, who cares if everyone does bad things, because bad things are just what important people have to do. Who cares if Barack Obama bombs people and doesn’t even try to prosecute bankers, because that’s all just his job, and he loves gay people and yells at bigots and his wife is smart and has great arms. Who cares if Hillary Clinton is best friends with Henry Kissinger, because she is a woman and so am I, and she stands up to men, and isn’t that what feminism is all about, finally getting into the rooms, finally getting to be the one to kill the people who don’t matter? Since my life was a fantasy, I had no trouble inhabiting a larger one.

It often strikes me that it is considered immature to be unable to believe bullshit. Think about the word globalization. It doesn’t mean cultures mixing, fusion cuisine, or a fun wedding of a rich Sri Lankan to a poor Swede. It doesn’t even mean free markets. It means access to new markets and especially access to cheap labor so rich people can make more money. That is all it means. If you happen to gain from side effects (see fusion cuisine, above) you might want to notice what everyone else, including you, is losing. But try saying that at a dinner party. Everyone would just feel sorry for you.

I just can’t stop thinking of—hmmm—The English Patient. This was a movie about good looking mostly white people talking complete rubbish to each other, the end. But it was based on a LITERARY NOVEL with LONG SENTENCES using BIG WORDS. It had RESPECTED ACTORS. PEOPLE DIED in it. Also, WORLD WAR II WAS THERE. Everyone had agreed to care about this thing, to call it good, to give it nine Academy Awards. But it was just a piece of shit sprinkled with glitter that everyone, including me, agreed to call gold.

Everyone talks about the country falling apart in November 2016, but maybe it fell apart in November 1996, when America went to see The English Patient. What if we had all turned to each other and said, “This garbage is our idea of rave-worthy cinema? Anyone else see a big problem here?”, and then there had been a massive riot?

Becoming poor was such a small price to pay to stop being so fucking dumb. I used to hear the saying “Politics is the art of the possible” as benignly self-evident. Now I know it is chastising, smug, and cruel. It’s not about cooperation. It is about agreeing that some people’s lives don’t matter. If you hear anything else in that saying, you’ve never wished you could just die because you couldn’t figure out how to make money.

I should mention that I realized long ago that the whole drama around getting on staff was completely one-sided. Ron and Julie weren’t actively refusing to notice me. As for Jennifer, I have no doubt we were real friends, but she was never going to sit up and realize that I was indispensable. None of it had anything to do with me. The publication didn’t have any cash. Everyone was worried about their own jobs. They cared about the reviews I struggled over probably about as much as they cared whether the toilets worked. Actually, no. They definitely cared more if the toilets worked. Wouldn’t you?

I hope it’s not too late for me to tell you the truth. The heart is not an organ of fire. It is just a heart, it is not special, and when yours stops beating, you will die.