The outbreak started just across the street from me. The explosion of cases, which began on May 15th, has mostly been traced back to “tea parlors” in Bangka, the district of Taipei where I live.

The coronavirus arrived suddenly in Taiwan. With thousands of cases reported in the past two weeks, the country is currently on level 3 alert. Many businesses and restaurants remain in operation, so this is still not a full lockdown, but public gatherings have been suspended, schools closed, and restaurants have all switched to take-out or delivery. It’s not clear when—or if—more restrictions are coming.

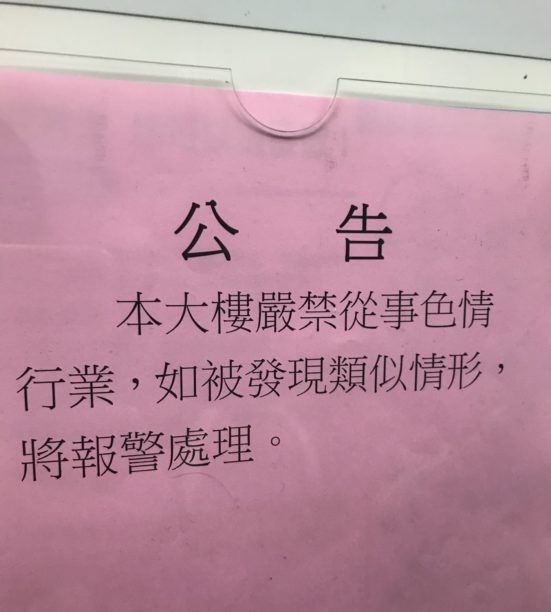

These “tea parlors” often host elderly men drinking alcohol or tea together, chatting in the company of female hostesses. Sometimes the hostesses sing karaoke while the men watch. There is sometimes a degree of sex work involved, though not always. These establishments are also known as a-gong-diam (阿公店) in Taiwanese Hokkien, literally meaning “grandfather store”—a reference to the age of their clientele.

The element of sex work is thought to be why the cases spread so widely and so fast. Taiwan has effectively employed contact tracing in the past, but that was not so easy this time, with many patrons reluctant to disclose that they were visiting tea parlors, or the names of their companions.

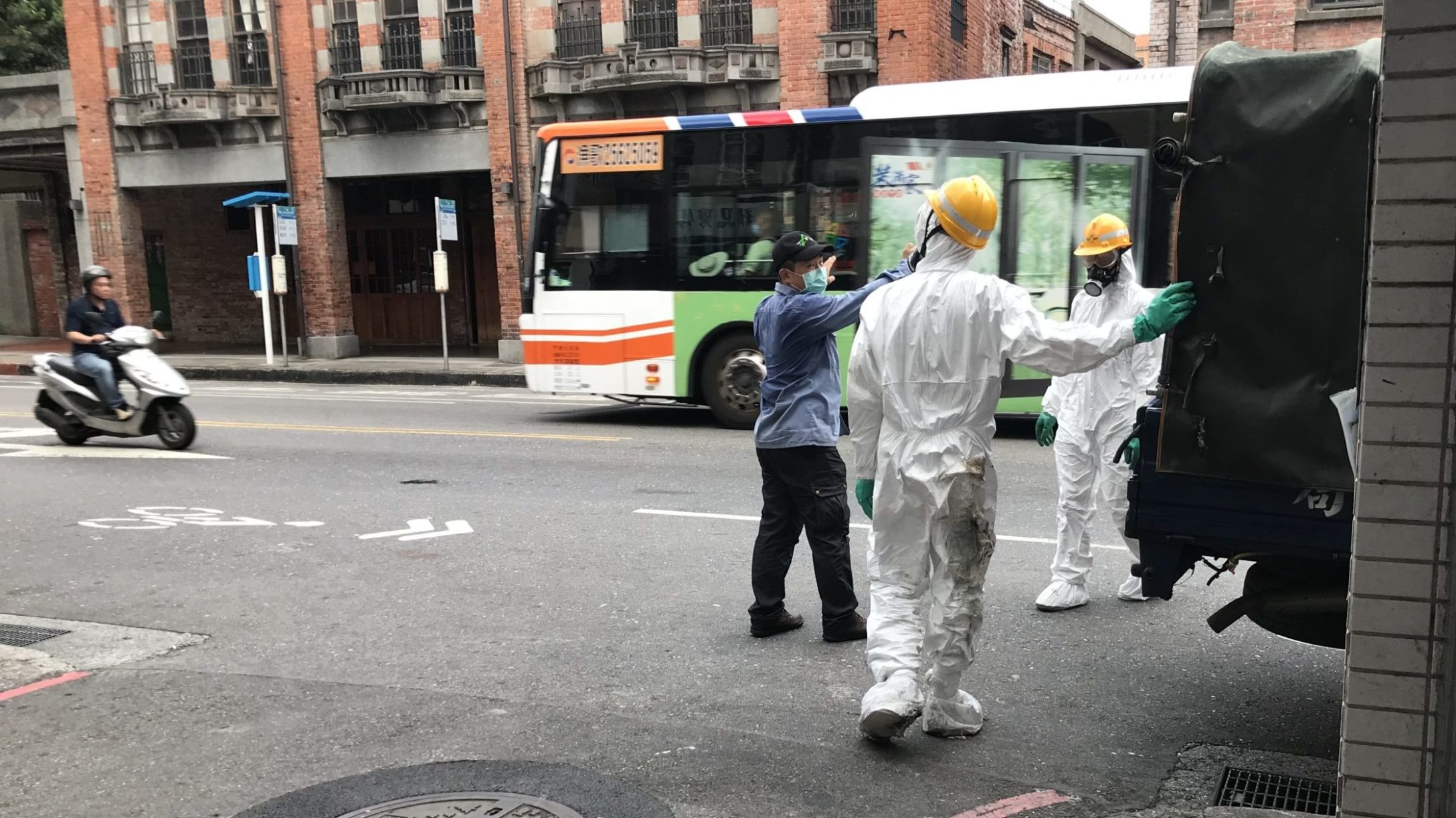

So now I can see the long lines snaking every morning around the Laosong Elementary School for the testing site at the Bopiliao Historic Block, a shipping and export center dating back to the Qing dynasty. Sometimes I see news vans driving around the neighborhood. Or I might hear the voice of the city mayor, Ko Wen-je, broadcast from a speaker truck, calling on local residents to get tested.

The wailing ambulance sirens are nearly constant at times. But more striking still are the moments of silence between the sirens. I’ve never seen the normally raucous Bangka night so quiet before.

It’s a bit strange seeing Bangka pushed so suddenly into the public spotlight. It’s one of the most distinctive parts of Taipei, being one of the city’s poorest areas, with parts resembling something like a red-light district, though sex work is illegal in Taiwan. Many sex workers here are migrant workers from China or from Southeast Asia, in Taiwan illegally. Whenever I walk home, past the many alleys full of a-gong-diam, they call out to me, asking if I’m looking for a girl or want a massage. The cliché is that only the elderly visit the a-gong-diam, karaoke establishments, and massage parlors offering sexual services in this area, because the sex workers in Wanhua are primarily older; younger sex workers are more commonly found in Linsen North Road.

However, I do encounter roving groups of young men sometimes, visiting the local a-gong-diam. Some of these young men give off a gangland vibe, but many seem quite average and unremarkable. I suspect that there are more younger clientele at a-gong-diam and similar establishments than one would think—a friend recently told me that he was surprised to discover how common this was when he did his mandatory military draft, which lasts for a year for people of his age and applies to all Taiwanese men.

Despite being the earliest Han settlement in what is now Taipei, the neighborhood was left behind by development, which first shifted north to Dadaocheng, and then eastward. Because of the low rent and relatively high number of migrant workers, the area is probably one of the most diverse areas in Taipei.

The area is also home to the majority of the homeless population in Taipei, who mostly gather in Mengjia Park. I’ve heard a few different explanations for that from local residents. According to some, this is because the many temples in the area feed the homeless, causing them to move to the area. Another explanation is because one of the hospitals in the area, the Ren-Ji Hospital, specifically takes care of the homeless.

According to other journalist friends that have done interviews of homeless in the area, a lot of the men seem to have ended up on the streets due to failed businesses, debt, gambling, or drug use. It’s more common for women to wind up there due to family reasons, relating to divorce, for example.

There’s also a sizable number of “quasi-homeless”—mostly elderly who live in low-cost housing with no air conditioning, as a result of which they spend much time outdoors. Because of their poverty, it can be hard to distinguish between them and the full-time homeless. Reportedly, because there’s been increased media focus on Bangka after the outbreak, this has caused most of the “quasi-homeless” to disappear back to their homes.

So it’s surprising to see that there’s been much stigmatization of Bangka as of late. When there’s a disease outbreak, people get scared, and they start to point fingers. By now the new coronavirus outbreak has spread far beyond Bangka, yet sometimes I’ll still see proposals to lock down Bangka, as though that would help—it seems more like scapegoating Bangka so that others can feel safe.

There’s even been social discourse referring to COVID-19 as the “Bangka Virus,” or claiming that scenes in Wanhua resemble the current outbreak in India; there have been incidents of Bangka residents being told to stay away from their co-workers in offices, with reports that the Want Want Group confined all its employees living in Bangka to a single floor of their building.

Least surprisingly, there have been attempts to shame sex workers and their clientele, and suggestions that nobody would ever travel to Bangka except for this. Even with current restrictions on public gatherings, I’m concerned that these manufactured tensions will lead to the targeting of migrant sex workers or of the local homeless population. I wouldn’t be surprised if the city government were willing to throw the area under the bus in order to maintain approval ratings.

In any case resources seem stretched across the board, including among the local organizations that have stepped up to provide aid to the homeless. My colleagues at New Bloom, the leftist publication we founded in the wake of the Sunflower Movement in 2014, put together a supply drive for the homeless, which, though successful, was still just a drop in the bucket. We’ve heard that very few resources have been allocated by the city government to local NGOs, including the basic medical supplies that they themselves need to stay safe. There are a few activists in the area who successfully ran for local office, but even they are having difficulty trying to find supplies to help the homeless aid NGOs.

In the meantime, life is devoted to daily news updates. There’s a large amount of misinformation and disinformation about the outbreak, and a paucity of accurate information available in English. Some of it is just due to confusion, while some disinformation seems to be of state origin—particularly with the Chinese government apparently attempting to stoke the narrative that the outbreak was of Taiwan’s own making, because of its unwillingness to accept Chinese aid, conveniently leaving aside the fact that China has thousands of missiles pointed at Taiwan.

Sometimes, due to naivete or cynicism, Western media eats these narratives up. You also see a lot of pandemic hot takes from people hoping to boost their profile, or simply reacting out of panic. I also find a lot of the English-language discourse to be characterized by “expat angst”—written by people who make much more than the average salary in Taiwan, and don’t realize that conditions are far worse for your average Taiwanese than for them, right now. I can’t deny that’s frustrating.

Where Taiwan had previously been idealized by the international world for its successful COVID-19 response, suddenly the country is being lambasted for its slow pace of vaccinations. Taiwan has had a very low supply of vaccines, with only enough to cover just over one percent of its population at the start of this outbreak—Western countries manufacturing vaccines have had large delays sending them to other countries, preferring to first finish their own domestic vaccination programs before distributing them elsewhere. As Taiwan had COVID-19 under control up until now, the need was not evidently urgent until a matter of weeks ago.

On reflection, the current round of lambasting and victim-blaming of Taiwan, and the previous idealization of its successful resistance to the virus seem like two sides of the same coin—artificial projections onto Taiwan from without.

For my part, I’ve been working to combat the spread of dangerous disinformation by getting the most detailed and accurate daily reports out there I can, as fast as possible. It’s exhausting. I’ve been live-tweeting the daily press conference held by the government, dashing off an article about it, and then keeping glued to the news 24/7, constantly doomscrolling for new developments. It’s meaningful and I think that’s what’s necessary right now, though doomscrolling and a 24/7 news diet aren’t great for mental health.

During the many protest movements I’ve been involved in, I’ve had to maintain constant, frenetic activity for a month or more. Sometimes, I think, this is what I live for—it’s what I can contribute, during moments like these, that makes me feel that my life has any modicum of meaning. But this time it’s a bit different. With protest movements, you’re out there in the streets, among others, and you have a clear enemy that you’re all facing—together. This time, I’m locked away alone in my room most of the time, and there’s no tangible opponent.

Still, there’s no choice but to soldier on, I guess. I know it’s been way worse in other parts of the world than it’s been in Taiwan, so far—even if things feel magnified to me by being near the center of it.